Brexit and the inauguration of Donald Trump as US President last month have polarised both nations that now share more than just a special relationship as their political systems go through upheaval.

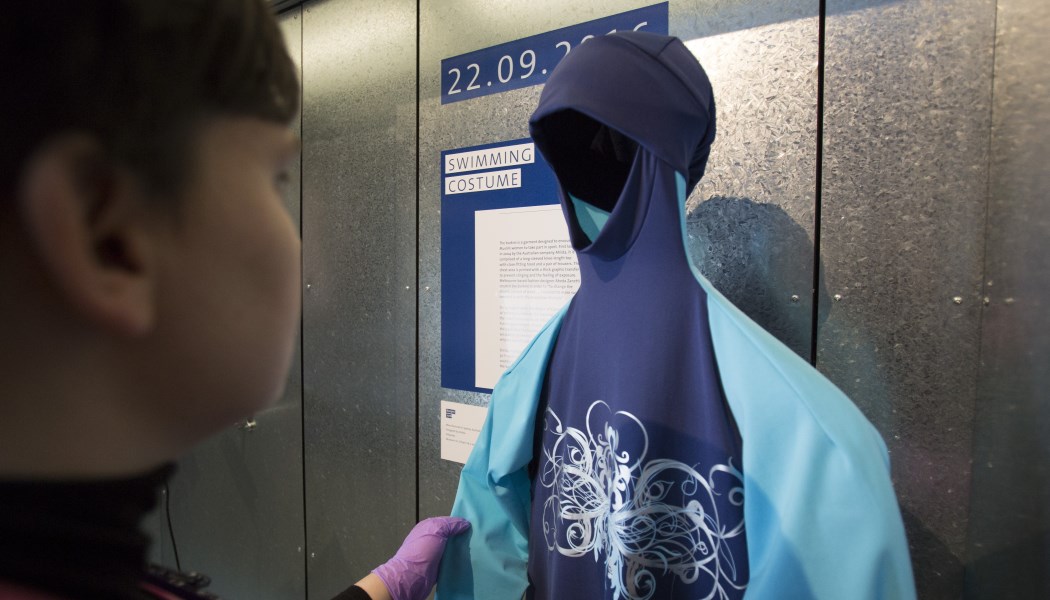

Last Friday a workshop was held at Derby Silk Mill entitled: How can the cultural sector respond to the Referendum? And the night before curators at the Museum of Modern Art in New York were rehanging Picassos and Matisses with a number of works by Iraqi-born architect Zaha Hadid, the Sudanese painter Ibrahim el-Salahi and Iranian artist Parviz Tanavoli. The former was a brain-storming exercise between museum professionals as a response to Brexit and the latter was a direct stand against President Trump’s travel ban on seven Muslim majority countries in the Middle East.

Each work of art rehung at MoMA was created by an artist from one of those seven countries banned and was labelled with the following statement: “This work is by an artist from a nation whose citizens are being denied entry into the United States, according to a presidential executive order issued on Jan. 27, 2017. This is one of several such artworks from the Museum’s collection installed throughout the fifth-floor galleries to affirm the ideals of welcome and freedom as vital to this Museum as they are to the United States.”

This was preceded the week before by statements by the American Alliance of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors against proposed cuts to the arts and in the UK the Museums Association published a Museum Manifesto for Tolerance and Inclusion and the School of Museums Studies at the University of Leicester’s six point plan to stand up to discriminatory politics by Trump and the rise of the far-right in the EU.

But what really caught people’s imagination was the 600 Women’s Marches that took place on 21 January across the globe in protest of Trump’s position on a number of issues including women’s rights. This led to many museums putting a call out for donations placards and paraphernalia used on the marches for their collections. Glasgow Women’s Library has since received offers for placards and clothes, and also received a Pussy Hat sent in the post, a symbol of Women’s Rights made especially for the marches. The only accredited museum dedicated to women’s lives will collate the material and use it for future talks and exhibitions.

“We are also awaiting a banner from the London March with a quote from Jo Cox donated by the Shoreditch Women’s Institute,” says Wendy Turner, Museum Curator at Glasgow Women’s Library. “You have to act quickly. The example I give is that there is not a lot of material from the Suffragette marches because that history hasn’t been collected. Now we are much more aware of contemporary collecting. We don’t want to say in five years ‘why didn’t we collect those banners’. We are collecting history for the future and have the evidence to say why it was important. We can also record the why, how and who these people marched with.”

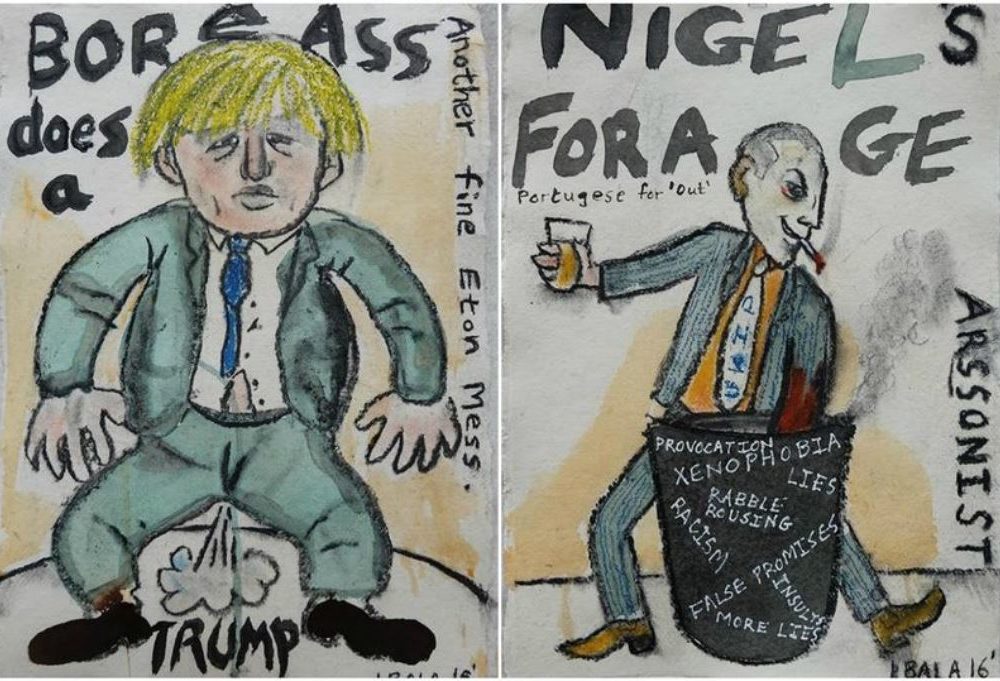

As for Brexit the reaction has been different, and although in a Museums Journal poll last March, 97 per cent of museum professionals said UK museums would be better in Europe, there have been few protests or special exhibitions. One exception was an exhibition at Penarth Pavilion Pier in South Wales entitled: Here is a Love, Deep as Oceans, which saw Artwork from pro-Remain artist Iwan Bala mocking the Brexit campaigners (and also Trump) and received complaints from residents of an area that had voted remain.

However, there have been many talks including the recent Happy Museum workshop and last year: How should museums respond to Brexit? Organised by the Midlands Federation of Museums and Art Galleries. There are also upcoming events where the EU Referendum will take centre stage such as at the ICOM-UK Conference next month entitled: Working Internationally in a Post-Brexit World.

“I think a lot of people are still trying to understand how they could effectively respond to Brexit rather than react against it,” says Tony Butler, who organised: How can the cultural sector respond to the Referendum? “What we wanted to try and achieve was to get people in our sector to think about the kind of values that drive the whole of our society, where the common ground is.”

Butler says in the UK, museums tend to dig deeper and are looking at these situations with a long-term viewpoint by trying to understand their audiences better and engage with them based on their values.

Recently he has been working with Tom Crompton of Common Course and neuropsychologist Kris De Meyer, who both spoke at the Happy Museum workshop, on the ideas of values and what motivates people’s decision making.

“The premise is that our society and politics have become more polarised and we should try and understand what motivates people to take the positions they do.”

This is characterized, says Butler, by the 52 per cent who voted to leave the EU and the 48 per cent who voted to remain. Another strickingly similar statistic that needs to be taken into account from the DCMS Taking Part survey is that 52.5 per cent of the adult population have visited a museum in the past year and 47.5 per cent have not.

“We need to understand why that is and good organisations will try and lessen those barriers and attempt to engage with the other half that aren’t coming to museums,” he says. “This is a step along the road to understanding the values of people that don’t engage with us.”

He says that if you think museums should have a wider role in society, other than just appealing to their core audiences, then organisations such as Derby Museums, which is a public civic institution, should take its role seriously in this area.

“There are very few public spaces and public institutions where these sorts of non-judgemental discussions can happen,” he says. “I’m not saying that museums should be seen as neutral spaces but they are places where people can come together and talk about and discuss issues of the day and values and I would say ‘If not here, where?’”

One of the problems arising with the debate about Brexit and Trump is that there is a lack of empathy with others’ perspective and this is something Butler says museums have to work really hard to change.

“In the short-term there are certain things that are non-negotiable: we should promote human rights and be intolerant of racism, sexism and homophobia, and be protective of minority rights and the rule of law. All of these should be non-negotiable for museums and if we are not doing that then we are failing. There was an initial reaction to the increase in racist attacks and a lot of museums like my own declared themselves as places of sanctuary. So I think there are things that organisations did in the short-term, which were absolutely right, including the Museum Association’s Manifesto for Tolerance and Inclusion, which is great.”

However, Butler says that museums’ role should be to focus on the long-term by using their unique perspective. By that he means collecting material in response to Brexit but not concentrating on Brexit as a separate entity as he thinks Brexit itself is a symptom rather than the underlying condition.

“And it’s the underlying condition we need to address. Why people feel disconnected from politics, why there is inequality in our society, social economic and political and they are long-term issues that our organisation really need to tackle.”

In the workshop the group also talked about the fact there seemed to be two camps in society: the progressives, who value universalism, and the conservatives, who value security and tradition.

“In Schwartz’s Value based theories that we were working on there’s an area that’s called benevolence and it mentions helpfulness, friendship and kindness, which both sets of people which self-identify as one or the other group felt very strongly about and that’s where the common ground is and where there’s potential for museums to engage with people.”

In the aftermath of the riots of 2011 Butler says there was a lot of discussion about the sector’s response and the feeling was that not many museums reacted to document and explain the causes.

“I think we do struggle to rapidly respond with public programmes to events and there are a whole range of practical issues behind that and we could improve in that area, absolutely. If there are situations where there is an attack on really important values like the Muslim ban for example, which I think museums have done really well to respond to, then it should be tackled but it is often not in terms of an exhibition, it might be a joint statement it might be an event.”

Derby Museums is about to launch a new project called Your Place in the World, which will use funding from the Wolfson and Esmée Fairbairn Foundations, that will utilise its World Cultures Collection as a means to talk to people in the community about their place in Derby and Derby’s place in the world.

“We will be thinking of local and global citizenship at the same time. But rather than go to community centres we are going to be going to boxing clubs and laundrettes and barber shops because communities are self-selecting and I think we have to try and work really hard to try and find where the genuine mix of people would be.”

This project supports Butler’s views that museums should find out why there are deep divisions in our society and find ways to bridge the gap by understanding and emphasising people’s values.

Main Image

The Women’s March in London on 21 January 2017. Wikipedia Commons