The Lost Palace launched an open competition in the summer to design a visitor experience that will utilise state-of-the-art digital storytelling to enable visitors to experience and reimagine the lost history of Whitehall Palace, the seat of many nation-changing events.

Whitehall Palace, of which Banqueting House is the sole surviving part, was once the largest palace in Europe; comprising 1,500-plus rooms over 23 acres – larger than Versailles or the Vatican. It was the main residence of British monarchs from the 1530s until it was destroyed by fire in 1698.

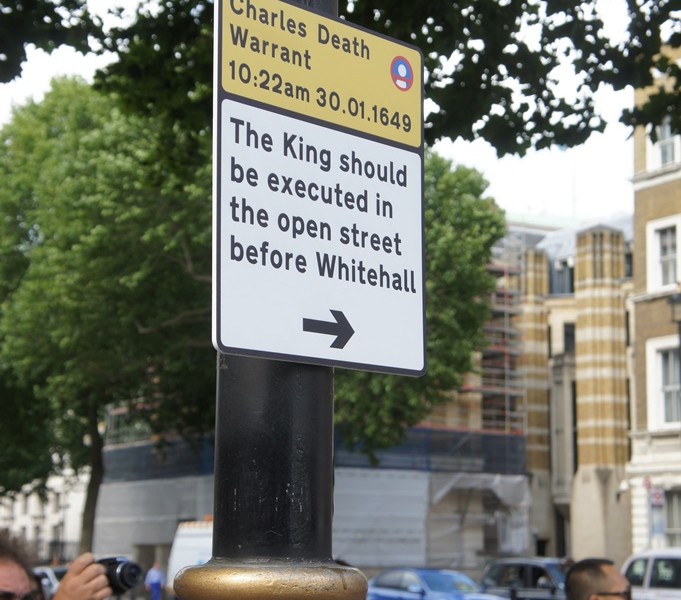

From next year visitors will purchase a ticket from Banqueting House and pick up the new device ready to explore the lost spaces and stories of Whitehall Palace. With the device they will encounter the characters that once inhabited the spaces while on Whitehall’s modern streets. It will turn today’s ‘Corridors of Power’ into playful spaces where history is performed and participated in.

“The aims of the Lost Palace project aren’t really any different to any other heritage project,” says Tim Powell, Lost Palace Project Manager, Historic Royal Palaces. “They are to tell the incredible stories of Whitehall Palace’s colourful history where they happened; to improve the visitor experience at Banqueting House; to increase visitor numbers by creating a new and unique visitor offer that appeals to new and existing audiences alike; and to illuminate the link between today’s political ‘corridors of power’ and the site’s past royal power.”

The difference with The Lost Palace project is, as the name suggests, it is telling these stories of a palace that no longer exists, which is why the team needed to create a whole new methodology for doing this, and is why the use of technology was explored.

In a heritage context Powell says he is not particularly interested in technology for its own sake and that using technology to do the same things they have always done often ‘just feels gimmicky’ – and these can quickly feel far more outdated than the traditional interpretation methods they were trying to replace.

“But with the Lost Palace, technology suddenly offers the opportunity to do something long wished-for but previously impossible – to offer experiences of the history that happened within a building which burnt to the ground centuries ago,” he says. “The wow should come from how the technology brings the storytelling alive, not through the flashiness of the gadgets,” he says.

By running the project as digital R&D, we also were able to involve our audiences in the process as never before

Powell believes The Lost Palace has a unique challenge when it comes to technology as visitors come to palaces to travel back in time – to escape the real world. “If we’re not careful technology can act as a barrier to what makes us unique – especially the overuse of screens and smartphones,” he says. “So we set ourselves the challenge of sticking to the same site-specific standards we’d demand in a palace interior for this palace-less digital project. No screens.”

Powell says that rather than assuming that they knew the best way to create a new experience, they chose to run a competition and let the creative and digital worlds broaden their horizons as to what it might be – and meet new types of partners in the process.

“For the same reasons, we were also aware that we’d have to follow a different process to the more typical commissioning model. Most importantly, the digital R&D route enabled us to build in audience feedback from a really early stage – by allowing our audience to help test the prototypes.”

Submissions came from across a whole range of new and emerging technologies – virtual reality, augmented reality, located audio, and many other interactive digital ideas. Powell and his team also encouraged collaborations between artists and technologists and received submissions from across the creative industries – from dance, theatre, fine art and architecture to game design and all sorts of other design disciplines.

“I thought we’d know the open call competition was worthwhile if it generated ideas we’d never have come up with ourselves. And with beating hearts, magic tricks, texts from the King and palaces made of sound, we definitely were beyond our wildest imaginations.”

The Lost Palace also offers a major new opportunity for HRP to expand its storytelling reach beyond Banqueting House and into a new high-profile Central London area, the streets of Whitehall. “Not being physically bound by a palace hugely extends the experiences of history we’re able to offer,” says Powell.

The Lost Palace project is continuing to work with two of the creative teams from the prototyping phase (see fact box left) to produce the Lost Palace 2016 visitor offer. These are interaction designers Chomko and Rosier, who made the ‘Heart of a King’; and theatre makers Uninvited Guests (with sound artist Lewis Gibson), who made ‘To Please the Eyes and Ears’. They will be collaborating with HRP in creating the overall concept and narrative, whilst being individually responsible for the elements which specifically suit their expertise. A bespoke technology platform that enables the whole experience is being made by Calvium Ltd, in response to the developing creative direction.

“However, this isn’t just a case of taking the two prototypes and combining them,” he says. “We’re asking them to apply their unique creative and technological approach to the much bigger challenge of the whole lost Palace of Whitehall. So whilst the most successful elements of both of their prototypes will be evident in the final version, it will be much greater than the sum of these two parts.”

The prototype testing phase was independently evaluated by Courtney Consulting – after a summer of intensive testing with a range of different audience types. These new ways of working involve organisations in the process more than ever before, which Powell believes is important to get an outside, objective judgement on the results. “Thankfully the report’s recommendations tallied exactly to the project team’s own responses.”

Both of the successful prototypes had three things in common. Firstly in creating sensory experiences of historic events – using binaural sound and haptic feedback respectively. Secondly, they made the visitor an active participant in the story, whose actions directly influence the experience they have of the history. And finally, they both created something that was previously impossible.

“For example, Uninvited Guests’ ‘To Please the Eyes and Ears’ didn’t just use binaural sound to create a recreation of Shakespeare performing Othello in the Cockpit Theatre, they also cast the visitor as Desdemona – an actor on stage, rather than an observer in the audience,” says Powell. “And Chomko & Rosier’s Heart of a King put the visitor in the footsteps of a historic character (often a stated aim of heritage interpretation) more directly that I’ve ever heard before – as the guardians of Charles I’s heartbeat.”

The team is confident that the Lost Palace in 2016 will appeal to a broad range of audiences, both as a completely new way of experiencing history for existing audiences – and one which will appeal to London cultural audiences who would typically be drawn to theatrical or design experiences rather than to heritage attractions.

“By running the project as digital R&D, we also were able to involve our audiences in the process as never before,” he says. “Bringing them in at a really early stage in the project’s developments – to test the prototypes – and letting their feedback actively guide the direction the project takes. People’s willingness to volunteer their (and their family’s) time to help us test was fantastic – and they told us they found the opportunity to help shape the project really rewarding.”

The Lost Palace will open to the public on 21 July 2016. Tickets go on sale in early 2016.

The Lost Palace’s five prototypes

The online brief was viewed nearly 3,000 times and over 100 creatives came to open days we ran at the Banqueting House. These resulted in 89 full proposal submissions. The following five were chosen to develop, based on their combination of storytelling power and interesting use of technology.

An East Wind, by PAN Studios and Seth Kriebel: an experiment in what can be achieved by using the minimum technology barrier – text messages. Each ‘player’ is a character from the palace’s history, by playing the game they enact an episode from

The Enemy Within, by Storythings and Anthony Owen: historical story delivered in episodes – most of which were listened to before arrival. Throughout these ‘suggestion’ and mental magic techniques were used to try and trigger the emotions of an historical event when the listener finally arrived on site.

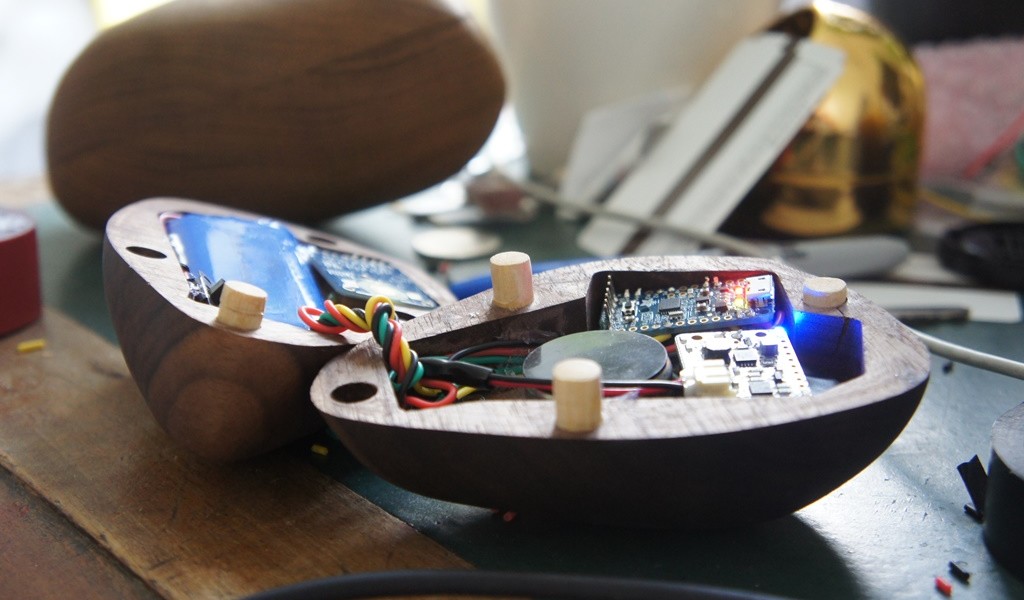

The heart of a King by Chomko & Rosier: a carved wooden object which beats with a haptic human heartbeat. By following the direction where the heart beats strongest, you are guided on Charles I’s last walk before execution. When you reach the site of the scaffold, the heart stops beating.

Oranges and Petticoats, by Splash & Ripple: an embodied choose-your-own-adventure story. You make choices by moving into different parts of the Lost Palace, so each visitor gets a different version of the story.

To Please the Eyes and Ears, by Uninvited Guests with Lewis Gibson: using binaural sound to create the Lost Cockpit theatre. The experiment was how sound can give the sensation of specific spaces – and how to turns the visitor into a character from the past.