A very important person once said to me: to be an interpreter, you must have a magpie mind. There is truth in madness: a mind attuned to ‘stealing’ the brilliant ideas of others who dedicate their lives to researching their particular interest (curators, academics, keepers of collections, archaeologists, historians…) is an essential ingredient. A mind that is journalistic in its seeking, policeman-like in its questioning, artistic in its capacity to make links, and heroic in its unfailing determination to champion the visitor’s point of view, at every step, through thick and thin.

Getting to grips with a major museum redevelopment project is always scary. A new team of people, whom you will be working with for maybe as long as 4 years, a new subject matter, the steep climb to finding and building a shared vision. The early days are terrifying and full of sleepless nights – many hours spent catching up on significant facts and just reading, reading, reading.

A Phone Call

One foggy day in October 2008 I received a call from Architects Pringle Richards Sharratt, with whom I had worked (while still at Event Communications) on the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry, Family Friendly Museum 2010. They noticed I had set up an independent practice – might I be interested, they wondered, in working with them to pitch for the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow? Little did I know that would be the beginning of a long and fruitful working partnership in which I was to re-learn interpretative techniques in order to fit them to an architectural field of vision.

A beautiful summer’s evening in London, 5 years later, and the team of architects, designers and interpreters huddled around our Waltham Forest Client, and celebrated with champagne: M&H Award for Excellence for Best Permanent Exhibition 2013, Art Fund Prize Winner 2013.

How Did We Get There? Or: the basics of interpretation

Interpretation is – never – information. There should never be a point when we suggest content that is purely about relating facts. I believe there are two reasons for this: firstly, none of us normally visit a museum to check our knowledge, as there are many more comfortable and satisfying ways of doing that, generally involving a cup of tea, one’s favourite chair or café, and a wireless connection.

At the William Morris Gallery the biographical timeline of the existing gallery became chronothematic, shifting towards an ideas-based narrative. Suddenly the objects would not be displayed as successive design developments, but as a sometimes wild variety of Morris’s frenzied interest for anything he committed to: learning Icelandic, weaving tapestries, mixing dyes with his bare hands, setting up a business, sketching wallpaper designs, falling in love, and out, setting type – inventing type, printing books, standing at Speaker’s Corner, composing music, protecting the countryside.

Visual inspiration for an issues based gallery focusing on his political stand came from an advertising campaign of a renowned current affairs weekly. Red would be our inspiration, and Fighting for a Cause is now less of a debating gallery but contains a controversial, thought provoking audiovisual.

The second reason why museums are about inspiration rather than information is: they are ‘places for muses’. They should encourage visitors to seek something that is unexpected, that pulls us out of the everyday. Learning something new can achieve sprecisely that. But the manner of learning is not necessarily through factual understanding. Clearly distilling and communicating key messages is essential in everyday life at all levels: when we look for a new home, in speaking with our children, in negotiating fees, in choosing fruit juice. Very rarely, however, are those key messages lifted out purely through intellectual intelligence. The emotional intelligence involved in processing them is pivotal. In interpretative terms, this makes the difference between content developed in museums that are thorough yet boring, and therefore lose the visitor’s interest, and museums that are captivating, full of life, and seem never-ending as visitors return, thirsting for more.

You can never ‘fail’ a museum visit. There is no ‘test’, no ‘exam’, no ‘requirement to pass’. How liberating is that! And how inspirational to develop content that frees the imagination, triggers curiosity, surprises people, connects seemingly disconnected elements.

Finding the Turning Point

William Morris: his name rattled around my brain when I put the phone down. Vague associations of dark wavy flower patterns on trellises printed on stale carpets of east London pubs, a confusing flavour of English Victoriana.

Surveys from the Gallery were telling us that 62% of people living within the prime local catchment area (20 min walk from the Gallery) declared themselves non white and non British. Potentially difficult content, with culturally distant target audiences. How would I ever find the winning hook for our concept?

In all interpretation projects, there comes a time when a single image, sometimes a quote, provides the turning point from which you never look back. It’s the decisive moment, and it – always – takes us by surprise.

Struggling, I churned over thoughts on biographical museums, investigated creative process – I read about ‘mind’-maps and ‘brain’-storms, dipping into Twyla Tharp’s The Creative Habit, and all the time making notes in the margin of Fiona McCarthy’s definitive biography. White noise instead of ideas. There seemed to be such a vast abyss between the museum’s presentation of the objects that embodied his work, and the ephemeral process in the artist’s mind. Which were we trying to communicate?

I looked again at portraits, pictures, poems, and pored over the Hollyer photograph of 1884, in the V&A collections. William is staring straight out, half pondering, but very direct, almost waiting to interject. Did Hollyer capture the ‘soul of the picture’? And more than that – did he capture what Morris was really thinking?

What was he really thinking? What made him tick? Could we get into his head? The phrenology head was a very simple way of illustrating this embryonic concept – and I then discovered that William was friends with E.T. Craig, a proto-socialist who was President of the Phrenological Society in 1888. The head divides up and names different areas that make up who we are: areas such as friendship, amativeness, sublimity, constructiveness, self esteem, destructiveness.

This was it – we’d stumbled on the key. The key that would help us unlock interest regardless of knowledge, the key that could make anyone relate to this man from Walthamstow. The introductory experience, Meet the Man, was born. We pursued this concept, agreeing that understanding what made him tick would be half the battle for engagement, and celebrating creativity by designing types of visitor experiences that appealed to a mix of learning styles, would be the other half.

.jpg)

Developing a Design Language

The interpretative philosophy I adhere to stems from creative thinking, and is laced with enjoyment. A museum experience should place visitors at its heart, presenting them with a variety of opportunities – and each of those is rooted in the content itself. This is what makes our job unique: no two projects can ever be the same, because the riches of each museum are so very different.

Early on in the process at the William Morris Gallery I developed an “experiential map” to guide the design development and remind ourselves that visitors, even when marketers have segmented and profiled them, are always different – and even learning preferences of the same individual can change during the course of a visit, depending on whether they have a toddler in tow, are on a date, or are taking the afternoon off because work is getting them down. Attitudes and interests vary because we are human. It follows that, whereas the narrative can provide a recognisable and consistent structure (the theory of the 7 basic plots), experiential learning can be designed with variety.

We would take visitors into a buffer zone, an introductory area, where they would have their first encounter. Crucially, this area is accessible from the Park, the shop, the café; it stands alone, and can be sampled independently. William lived in this house – the room sets the mood for the initial moment of recognition: that something (a location) is shared between the visitor and the protagonist.

Then, the start of a narrative experience that, rich in objects and stories, traces his love of companionship, the crazy university years, his friends and family, their wild days. Designed as an entry experience, it pulls you into the personal story, and functions as a first gathering point: visitors are welcomed in as companions, part of the brotherhood. Making art together, making music together, travelling together – physically and imaginatively through the medieval cities of France and the myths of chivalrous knights.

.jpg)

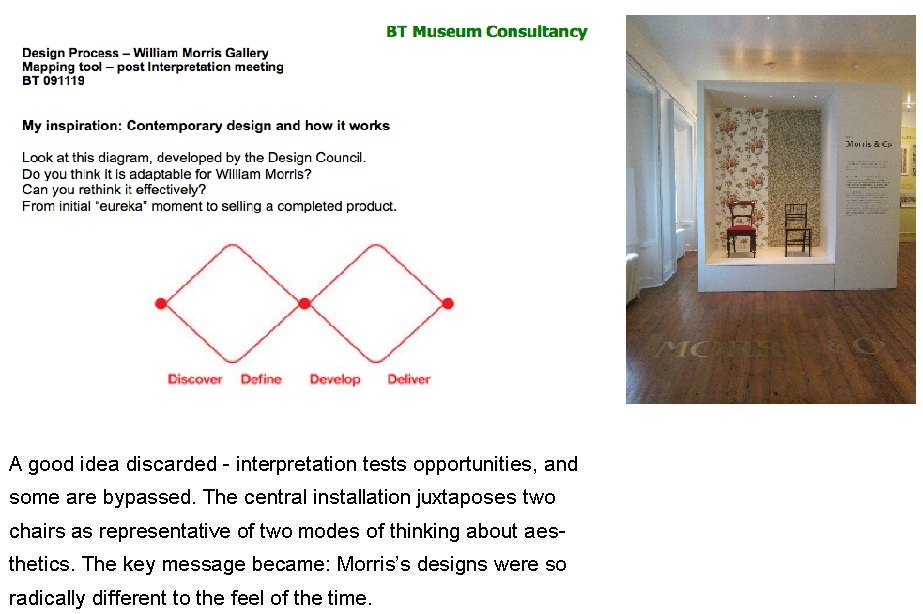

Other experiences followed – their adjacencies and sequence of discovery determining how we could vary the pace. The Story of the Firm continues the friendship and turns it into a business proposition. We dug into primary research into the contemporary design industry as well as the sales figures of Morris and Co., and developed an original idea to explore the process of creativity that was obviously too formulaic. A great idea at the outset, using a diagram from the Design Council, to explore the steps of creative process. But one that got lost – the iconic objects that were to occupy the nodes of the diagram never found, the simplicity of the process never tested on William Morris’s practice. (The touch screen Running a Design Business interactive is hugely successful.)

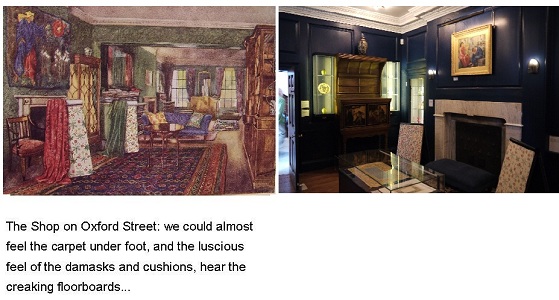

One area close to my heart is The Shop gallery. Hours spent inside John Lewis surreptitiously watching people feel fabrics, handle samples, an absorbed and aspirational look on their faces. Yet more hours reading about William’s knack as a poet-salesman, and his unequalled capacity for using words to describe colours: “the most ravishing yellows; what people call amber”, “dullish pink shot with amber, like some of those crysanthemums we see just now”. Orange and pink – a far cry from the William Morris I had assumed.

The Shop was designed as a social, active, hands-on, experiential area. Shopping is a form of leisure with which we are all familiar today, so stepping back in time across the threshold of his boutique at 449 Oxford Street, was a delightfully instinctive activity that required no meta-interpretation. The curators then whet our appetites with this original picture. And the sensitivity of the design did the rest.

A Final Word

Projects like the William Morris Gallery come around possibly once in a lifetime. We owe a debt of gratitude to the London Borough of Waltham Forest for having championed the vision and allowed the Design team to explore ideas somewhat beyond the pale. Personally, too, for the many hours of creative thinking it inspired. It is a humbling thought to think how far we travelled as interpretative companions. Writing this today, I remember the discarded ideas as much as the successful ones. I am reminded, too, that the Gallery has only begun its story, and I wish it – and all who visit it – well.

7 Steps to Interpretative ‘Enlightenment’

- Own the vision. Interrogate it, say it out loud, ask your museum team to express it in their own words. Once you’ve defined it, stick to it. My mantra for the development of the William Morris Gallery became for the museum to help people in Walthamstow ‘own’ William Morris. Break down the barriers of the past. Increase numbers of people visiting from different cultural backgrounds. Increase their enjoyment.

- Be brave and look carefully at generic learning outcomes – or any other learning framework that works for you. What are they? No, really – what are they? In relation to William Morris, an early exercise found that take away messages included “Stand up for your beliefs” “Get your hands dirty trying something out” “Never feel intimidated” “Start your own business”.

- Multitask. Interpretation is about creative flow, paced experiences, different learning styles. To bake that perfect pie, you need to pick the ingredients. Exploring wordclouds, sketching, doodling, talking, watching a documentary, googling visual stimuli, reading aloud. Interpretative ideas emerge from free play. In his words: “If a chap can’t compose an epic poem while he’s weaving a tapestry, he’ll never do any good at all”.

- Be playful. As an interpreter, one should never shy away from asking questions of the experts, and trying out new connections. Creative ideas will inspire people to be creative themselves. The world you inhabit is your store of creativity.

- Be honest. Interrogate the brilliant ideas, subject them to thorough scrutiny. Ideas are great, too, when they can be left behind. They are like stepping stones to something greater – a fully fledged interpretation strategy.

- Choreograph the experience. Think of yourself as a dancer, and make use of juxtapositions, tensions and drama. Creating multisensory experiences means harnessing emotions: seek out the soundtrack – if the museum were music, would it be piano sonata or rap?

- Be determined in taking the narrative framework into the detail. Telling stories with objects means selecting the objects, re-imagining them, using them as springboards to other content, as characters in a story. Always be faithful to the overarching story.