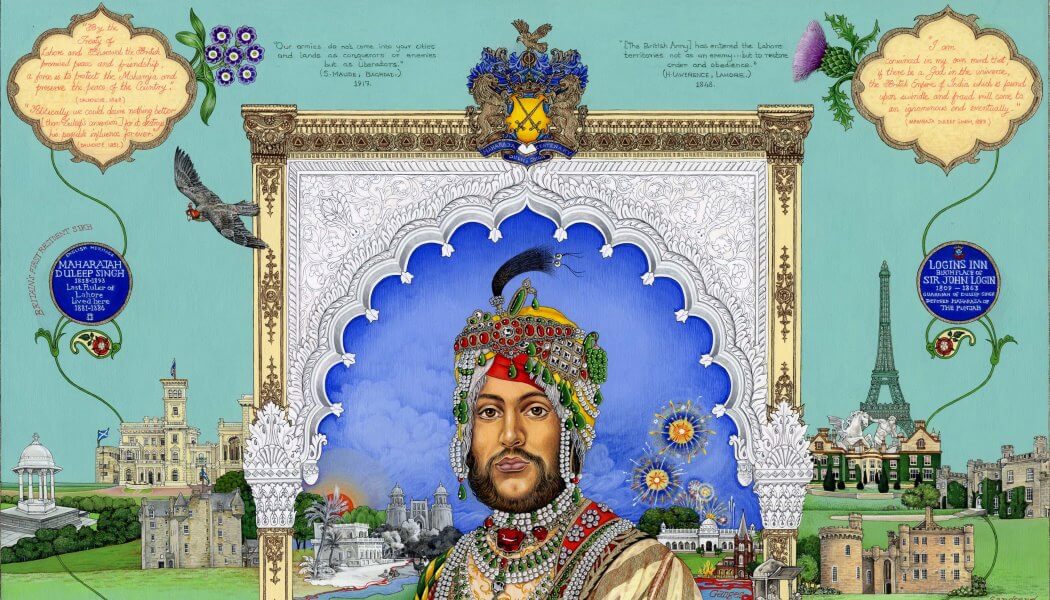

Alongside displays of beautifully crafted 19th century jewellery and intricate miniature style paintings from the 18th century is a newly commissioned painting, Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh by acclaimed artists The Singh Twins, offering a contemporary interpretation of the story.

The historical background of the exhibition covers the period of the British East India Company, from the beginning in 1600 to its end in 1858 and its two protagonists are Scot Archibald Swinton, who served in the East India Company’s army at the beginning of its military expansion, and Sikh Maharaja Duleep Singh whose empire was lost due to its expansion paving the way for the British Indian Empire.

Duleep Singh – National Museums Scotland

“At the core of the exhibition are two men whose possessions are witnesses to particular moments in this history,” says Friederike Voigt, Senior Curator, Middle East & South Asia, National Museum of Scotland.

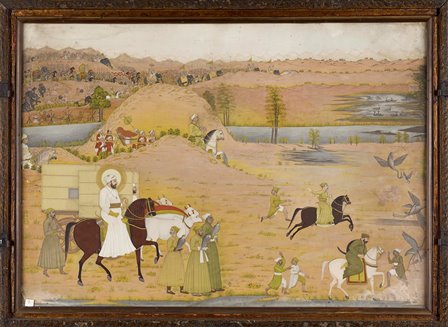

Swinton collected paintings that feature some of the Moghul rulers and court officials with whom he came into contact and documents of significant events he experienced while Duleep Singh had an extensive collection of jewellery and coins.

“I want the visitor to experience Archibald Swinton’s miniatures and Duleep Singh’s jewellery as testimonies to the choices they made within the confines of the historical circumstances by which they were driven,” says Voigt. “Another aspect which I hope this exhibition will convey with the painting Casualty of War: A Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh by The Singh Twins is that objects can be re-interpreted and made relevant today in a different way. I trust that the painting will inspire a dialogue, spontaneously in the gallery and lasting in society. This exhibition is also a great opportunity for visitors to get an insight into our conservation work and scientific research carried out in preparation of this exhibition.”

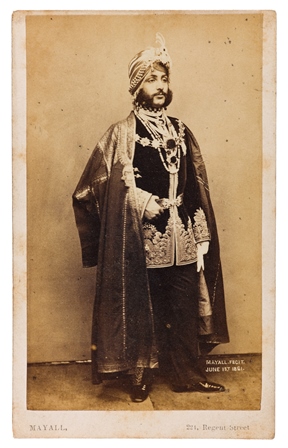

Most of the objects in the exhibition come from Museum of Scotland’s permanent collection and include Mughal jade and rock crystal carvings, a fine Indian trade textile from the Coromandel Coast, and coins and weapons of the East India Company. One of the key exhibits is a group of gold jewellery formerly in the possession of the Maharaja Duleep Singh. Duleep Singh was deposed from the throne of the Punjab by the British in 1849 and exiled to Britain, aged 16.

“These ornaments were heirlooms, some of them probably dating back to his father’s, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s time such as a pair of makara-headed bracelets (The makara is a mythological creature with a head of a crocodile),” says Voigt. “A rather unusual piece is a large sample of rock salt. It comes from the Khewra salt mine near Pind Dadan Khan, which is in Pakistan today and was given to the museum by a Scot working in the Punjab in the 1860. This salt mine once belonged to Maharaja Ranjit Singh and was inherited by Duleep Singh.

Necklace of rock crystal with a green glass bead and silk threads. Northern India 19th century – National Museums Scoltland

“After the annexation of the Punjab it was confiscated by the East India Company and exploited for its own benefit.” Indian Encounters will also shows a book, on loan to us from the National Library of Scotland, which was written by Duleep Singh. In this publication he claims back his confiscated property, documenting the lost revenues from the mine, which today remains the world’s second largest of its kind.

By focusing, in part, on the stories of Captain Archibald Swinton and Maharaja Duleep Singh and some of the items they owned or collected, Indian Encounters offers a glimpse into the affect relations between the two countries had on individuals. Fourth son of a landed Scottish family, Archibald Swinton went to India in 1752 and gained employment in the service of the East India Company. His diplomacy and profound knowledge of Persian, the language spoken at the Mughal court, became crucial for the Company’s negotiations with the Mughal Emperor.

“Swinton collected Oriental manuscripts, and miniatures painted in the court style of Murshidabad, which prominently feature in the exhibition,” says Voigt. “They represent the ruling elite of Bengal at that time. We are indebted to Sir John Swinton for lending these fine works of art to us.”

The ‘Great Mughal’ hunting crane with hawks, by the Mughal artist Hunhar. Photograph by John McKenzie

When he returned to Britain in 1766, Archibald Swinton was accompanied by a learned Muslim from Bengal, Itisam ad-Din, who later wrote a travelogue about his trip to Europe, including his experience in Scotland where he stayed at Swinton’s house in Edinburgh. This is the earliest known Indian account of European culture and society.

In the case of Maharaja Duleep Singh, his story tells of the loss of an empire and homeland, status and identity.

Following the Second Anglo-Sikh war he was deposed from his throne and the Punjab was annexed by the East India Company.

Duleep Singh was exiled to Fatehgarh, in northern India and appointed a guardian, John Login.

After a childhood at the Sikh court of Lahore, he was expected to embrace Western culture and to live the life of a Victorian gentleman in his exile in Britain.

“The jewellery in our collection symbolises his diminished fortune. Duleep Singh’s son Victor sold large parts of his father’s inheritance at an auction in 1899, including these ornaments,” says Voigt.

Pendant – Hindu goddess Devi seated on a lion opposite Mughal emperor Hanuman. Gold, rock crystal, emeralds and rubies. Northern India 1800-1850. National Museums Scotland

“Major Donald Lindsay Carnegie, a Scottish numismatist, finally bequeathed them to us as part of his coin collection.

“In recognition of Maharaja Duleep Singh’s importance to the Sikh community we commissioned British Sikh artists The Singh Twins with a painting exploring the significance of his jewellery today.

“The painting in miniature style is a key object of this exhibition, bridging past and present.”

The painting was launched in March in Stromness, Orkney, the birthplace of John Login, Duleep Singh’s guardian.

Voigt says that the British encounter with Indian culture was significant and meant that Indian artistry was embraced and became an established trend within European decorative taste.

“Craftsmen started to make consumer goods for the Western market, ranging from textiles to furniture such as the marble table top on display which is finely inlaid with differently coloured stones forming a chess board surrounded by delicate flowers,” she says.

“With the decline of the Mughal Empire luxury objects made for courtly patrons became highly collectable.

“For example, we bought a selection of carved jade and rock crystal objects from the collection of Colonel Charles Seton Guthrie when it was dispersed after his death in 1874; Guthrie had built his famous collection of Mughal hard stones while serving in India.

Rear view armlet – decorated with enamel on gold – Northern India 1800-1850. National Museums Scotland

“Another aspect is certainly that Britain has become a multicultural society. For example, Maharaja Duleep Singh is believed to be the first Sikh resident in Britain, arriving in 1854.

“Today there are close to half a million Sikhs born and resident here. His journey from Lahore to London paved the way for generations to come.”

However, Voigt points out that a lasting legacy of British rule in India, and a tragic moment in history, is the partition of the country in August 1947.

“As a result Pakistan, India and Bangladesh were formed, and the Punjab and Bengal, the very two provinces represented by the two men featured in the exhibition, were divided between these nations,” says Voigt.

The idea of this exhibition grew out of a combined curatorial and analytical research project on Maharaja Duleep Singh’s jewellery and Studio SP were commissioned to design the show.

“Central to the brief for the exhibition Indian Encounters, was the interpretation plan,”

Says Shanta Dhariwal-Robson, designer at Studio SP, which specialises in the design of permanent and temporary interpretive displays.

“It was critical that the collection was viewed in a specific narrative sequence, incorporating several themes in a small space, and displaying over 100 objects.

Wooden box decorated and coloured with lacquer and exported by East India Company to Britain

“It was important that the aesthetics of the exhibition were representative of India, for example the patterns, colours, textures and shapes.”

Dhariwal-Robson says that working closely with the client team was essential to ensure that the curator’s interpretive vision was matched by the physical design and aesthetics of the structures, graphics, colours and floral motifs used throughout the space.

“Archways creating glimpses through the space, allow the exhibition to feel intimate, while creating a sense of discovery for the visitor,” she says.

The most challenging aspect of the installation of the exhibition, says Dhariwal-Robson was the planning and coordination of the sequence of installation.

“There are several cases that are double sided, and therefore the installation of objects involved careful planning in regards to the positioning and sequence of case plinths and object labels, as well as the objects themselves,” she says.

“Through discussion with the client it was decided that we would recycle several case plinths from the previous exhibition in order to reduce the amount of materials used.

“This allowed us to focus more budget towards the object mounting, as we wanted to create dynamic case displays which would ensure the main focus of the exhibition were the exhibits themselves.”

Indian Encounters is a free exhibition and runs from 14 November 2014 to 1 March 2015.

Back to top