I was at a committee meeting for the Natural Sciences Collections Association (NatSCA), where the other committee members and I discuss ways in which we can promote and support natural science collections. Amongst other things, we were meeting to plan the upcoming conference and AGM, discuss and organise new training opportunities, and prepare our peer reviewed journal. The subject specialist group is very active in being an accessible network for staff in the museum sector, and is extremely keen to increase awareness of the importance and use of natural science collections.

There are a number of subject specialist groups in the UK, all aiming to support the collections and the staff in that area. Today, these groups are becoming more and more vital. In recent years, the poor economic climate has resulted in many local authority cuts, with museums having to make big reductions in their budgets. This has led to redundancies and restructures in several museums, resulting in loss of knowledge, reduced access to collections, and in some instances even loss of collections.

Many of the restructures have resulted in merging roles, where there is now a ‘Curator of Social History and Natural History’ or a more generic Collections Officer looking after art and archaeology. Should curatorial posts be amalgamated in this way, washing our hands of the subject specialist?

Quite simply, no. And for some very important reasons.

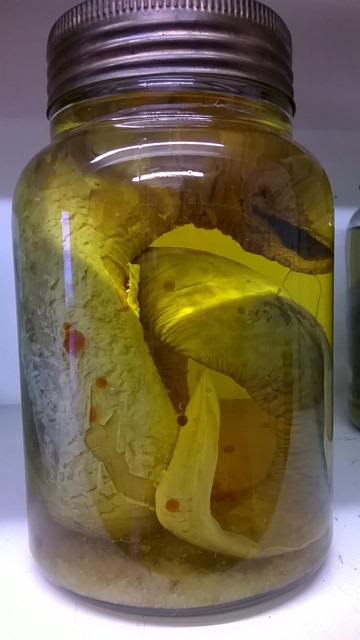

A specialist curator is someone who has had training in that subject area. I for example, studied Geology for my undergraduate, and Biology and Chemistry for my Masters. This background, along with some years volunteering in museums, has given me a good understanding of natural science collections. I have an understanding of taxonomic relationships between organisms, the chemicals involved in preserving specimens, relevant legislation and health and safety issues relating to collections, what information is needed for researchers, and where it’s appropriate for destructive sampling to take place.

These are all common topics which crop up on a regular basis in my job. But how could someone without that background knowledge know about these things? (My good friend and museum worker Mark Carnall has written about subject specialists more eloquently than I ever could.) Likewise, I do not have the background understanding to care for art of social history collections, which have their own specialist knowledge.

Loss of knowledge is the first domino to fall, with knock on effects for entire collections, and potentially the institutions that house them. Without someone who understands the collections, they will not be promoted to researchers, artists or schools. Without the proper understanding they may end up being neglected. There is also the very real danger that collections will be used without understanding the real hazards, leading to health and safety issues for staff and the public and legal problems for organisations.

Despite being the most popular gallery in museums for the general public, natural science posts have declined by over a third in the past ten years. This is why subject specialists such as NatSCA are even more relevant. (There is another subject specialist group for natural science curators called the Geological Curators Group.)

Museum curators are not experts in everything they look after. Natural science is a huge area covering minerals, fossils, insects, plants, lichen, vertebrates, invertebrates and more. Natural history collections are possibly the most diverse of collections; unsurprising since they attempt to represent the entire diversity of the natural world through time. In smaller regional museums there is generally one curator looking after all of these collections. I am not an expert in plants, but I understand how they are organised, how fragile they are, how they are used for research and the possible health hazards. I also know where to go if I need help.

Subject specialism is not elitism – quite the opposite. All curators, whatever specialism they have, know their collections. They understand the stories behind objects, the risks associated with some. Using their knowledge enhances the museum collections so much more, and this is what underpins a museum’s ability to share their collection and make it available to everyone.

Sitting around that oval wooden table, listening to my colleagues and friends talk passionately about the support they are giving to the wider museum sector that day was inspiring. It made me smile. I felt as though I was at home.

For more information about NatSCA see the website or follow on Twitter: @Nat_SCA.

More information on the Geological Curators Group can be found on their website or by following them on Twitter: @OriginalGCG.