One of the most beautiful, perhaps the most beautiful, characteristics of the human species is our innate curiosity. Our aching desire to find answers had led this naked, bipedal ape to land robots on another planet, and even successfully land a spaceship on a moving comet!

Our wonder to challenge the realms of what we think is possible resulted in turning the gorgeous poem The Dream of Gerontius into a powerful symphony, where notes of music played at exactly the right time causes vibrations trembling through our bodies creating a range of incredible emotions.

Our curious mind is constantly looking for answers and the more we look, the more we realise, how amazing the world around us really is. When writing The Sublime and Beautiful in 1757, Edmund Burke wrote, ‘The first and simplest emotion which we discover in the human mind, is Curiosity’.All of us think about that odd thing we have just seen, even if it just for a fleeting second. That is our instinctive curiosity. Quoted in 2010, Sir David Attenborough went a little further; ‘An understanding of the natural world and what’s in it is a source of not only great curiosity but great fulfilment’. Our natural curiosity, when fed, enhances our understanding of our world, and naturally enriches our lives.

Children are naturally curious about the world around them. In evolutionary terms, this makes survival sense; we all need to learn what is a friend or a foe, foods that can or can’t be eaten, as well as understanding the limits we can individually reach.

For some children the curiosity fades: not because they lose interest, but because there is no one to answer the questions, or encourage that spark of wonder within. But there are those who do inspire and stimulate that curiosity so that it continues to grow. This is where the beautiful curiosity within is most special; where it is passionately shared and encouraged.

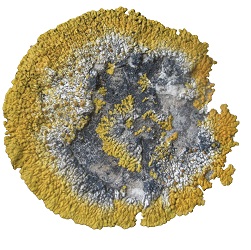

The enigmatic lichen Caloplaca flavenscens, permanently attached to a rock where it will feed off the nutrients. Plymouth City Council (Arts & Heritage)

Museum curators (in all departments) are in an extremely privileged position to really inspire new ways of looking at things and stimulate curiosity. Perhaps the most wonderful way we can enhance a sense of pure awe at the world is through public enquiries. Enquiries are a wonderful opportunity to talk one on one with someone about something they have found. By making a conscious decision to take an object into a museum, or email in a photograph, automatically shows that this person wants to know more. To the curator, some enquiries are quite fun, others may be something fairly obvious, and sometimes we are just as curious as the enquirer. But to the enquirer, their object is amazing. They do not see it as funny or obvious, to them it is special, and rightly so, for they found it. They may not know if what they found is a beetle or a bee, but by getting in touch with a museum, we can see they want to find out. What’s more, they want to know more than just what it is. Anyone can jump on a computer and identify a moth, or a fossil.

Sometimes the most curious bring in the most bizarre. A slimy rubber toy lizard thought to be a real lizard.

I have had a photo of an enormous ant 30 cm long, with massive jaws sent to me. It turned out to be a plastic toy ant with a little bit of mud on it.

By bringing something in shows they want to share their excitement of their discovery and talk to someone about it. It doesn’t matter that it may just be another ammonite fossil, or a piece of slag and not a meteorite. For the enquirer, it is special. I love all enquiries. From the good old regulars to the somewhat bizarre, I never know what people will bring in next. Museum curators get a lot; people popping in, some send emails, others call up. My favourite enquiry has to be from that wonderfully curious mind who is asking about a fossil or an animal on behalf of someone else; they themselves look at things differently and want to discover more, but they are also extremely passionate about sharing their curiosity. I recently received a number of photos of fossils from a curious mother who has two curious boys. They were fairly common Jurassic fossils, an ammonite, a belemnite, shells on an ancient sea bed. Replying to say just that would not be the most inspirational of responses. Not only would they stop looking, they wouldn’t bother to get in touch with the museum again. I see no harm in adding in some extra quirky information, as long as it is true. Adding a little magic to an enquiry takes no time at all. Just a touch of passion, and a sprinkling of enthusiasm, which all curators have.

A wonderfully preserved gorgeous little belemnite fossil (from an enquirer) with a hand for scale.

A little search shows what other fossils can be found in the same rocks, so a belemnite suddenly becomes this live animal thrusting itself through the water, catching crabs and shrimps with their tentacles whilst Ichthyosaurs splash above in the clear warm waters. Bringing to life a fossil sparks the imagination for those children (and their mother).

They are suddenly able to see that hard grey fossil as a real moving thing, in an environment long vanished. The moment of curiosity doesn’t stop with the reply, they talk about the fossil they found enclosed in the rocks; a creature they were the first to see in 150 million years.

Our need to find out more is a beautiful thing. From wanting to learn about ancient life, to how the Masters gently brushed their strokes on canvas, our questioning minds are never satisfied.

Museum curators can inspire and encourage this desire to find out more. And it should be encouraged, for these are our future astronauts, or the future palaeontologists.

A less obvious reason curators are lucky to be able to inspire, is that it brings families closer. By discovering more about the fossil they found together, they talk about it, and the next time they are out, they are exploring and discovering together.