Exhibitions do not have to be huge in scale to inform and amaze and the British Library’s new show Lines in the Ice: Seeking the Northwest Passage is a case in point.

With a small budget, a tight timeline and limited installation options museum design consultant, Andy Feast has created a colourful and absorbing display in the library’s ground floor entrance hall.

Using the maps, books and objects taken from the Library’s collection and some loaned objects, Feast has worked closely with lead curator Philip Hatfield to tell the history of expeditions across the Arctic.

Included in this is one of the most famous attempts by Sir John Franklin in 1845 to chart the remaining 500km of unexplored coastline following two previous exploration.

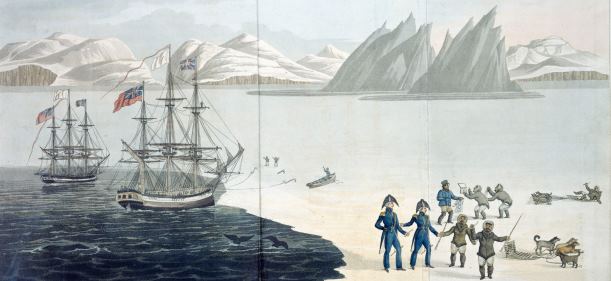

John Ross, A Voyage of Discovery, 1819

Franklin, a Rear-Admiral in the Royal Navy, was made expedition commander of 129 men who all lost their lives when their two ships ran aground. One of the ships, HMS Erebus, was finally discovered in September off King William Island.

“The brief was to create an engaging and vibrant environment to best show off the collection of maps, books and documents that illustrates the travails of the early European Explorers into the Arctic and Northwest Passage,” says Feast.

“The proposition was exciting for us; these shows rely on a seamless connection between the graphic and the three-dimensional structure.

“While the maps and books carry the content it is important to try and lift the subject matter, they can demand support in terms of context and very often scale too, a book will can only convey a small amount of the subject matter, a snapshot on the open page.

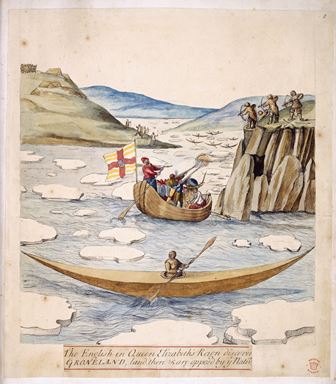

A skirmish between Frobisher's men and Greenland inuit, 1578

“Our job is to animate these artefacts, to add that scale and drama while allowing the objects to lead. Texture and colour can be a useful backdrop. Effectively the project is a real opportunity to push the parameters of the environmental design.”

This has been achieved by designing a multi-layered exhibit with boards illustrated with bubbles and differing shades of white and blue, giving the impression of icy conditions.

There are also glass bubbles projected from the walls with books opened ready for visitors to read a passage.

“For this scheme, the focus was put into wrapping everything in a graphic texture, its light and playful, provides opportunities to introduce value adding images stories, and ultimately reinforce the story and the concept,” says Feast.

Photographs have been blown up and characters such as Roald Amundsen, the first person to traverse the Norwest Passage between 1903 and 1906 – and who would later go on to be the first to discover the south (1910-1912) and north (1926) poles – take prominence.

“Since I started working as a curator at the Library I've always been struck by how many human stories there are embedded in this bigger narrative of Arctic exploration, international politics and the quest for resources,” says Hatfield.

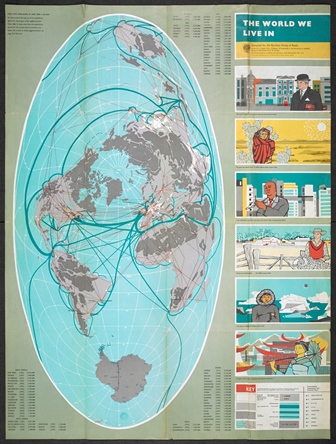

The world we live in, c 1958. British Library

“There are the well-known stories, Franklin and his men eating their boots during the 1819-22 expedition, but there are also many smaller notes dotted through a collection such as the British Library's.”

The fascination and determination to find a viable Northwest Passage to navigate across the Arctic Sea was matched by the intrigue and desire for news of the expeditions by those they left behind, including a captivated public.

It was a massive undertaking and Franklin’s took three years’ supplies with him on his ill-fated last mission, adding to the drama.

“The accounts and stories of the crew published in on board newspapers such as The Illustrated Arctic News and illustrations of men playing cricket on the ice in Capt. Parry's account of one of his expeditions all speak to how men experienced these expeditions once the initial thrill of adventure had worn off,” says Hatfield.

This story of endeavour is one that continually interests academics and the public which is why the exhibition still resonates.

“The idea for Lines in the Ice actually grew out of a 2013 proposal for a collaborative PhD looking at the history of polar exploration and its use in contemporary politics,” says Hatfield.

“While I was putting together this proposal I realised there was a fascinating story here that our collections were uniquely placed to tell – that of the long arc of European and North American interest in the Arctic.

“The Library's history of collecting globally means that Lines in the Ice can tell this story not just from a British perspective but also consider that of indigenous peoples and other nations, in particular America, Canada, France, the Netherlands, Norway and Russia.

“Fittingly, the PhD study, sponsored by the Eccles Centre for American Studies and Royal Holloway, University of London, is now at the end of its first year and both the student, Rosanna White, and supervisor, Klaus Dodds, have advised on the exhibition's development.”

As well as the intrigue surrounding the adventures is the ongoing political backdrop of climate change and how this is affecting the Arctic and many other issues not too dissimilar from those in the 19th century.

“Current discussions about the Arctic, focussing on trade routes, access to resources, land ownership, and so on, are strikingly similar to the reasons why men like Barents, Frobisher and Franklin were drawn to the Arctic; in many ways all that has changed is the desire to find gold has shifted to finding oil,” says Hatfield.

The exhibition has made use of the wide range of maps, photographs and sounds also housed at the British Library supplemented by some key loans, carved Inuit maps from the Scott Polar Research Institute and an Inuit oral history from the Canadian Museum of History.

“The strangest item on display is definitely a promotional book about a 'boat-cloak', an inflatable rubber coat used by explorers such as Dr John Rae to chart the Northwest Passage,” he says.

“A close second is the very haunting sound of a flock of Whooper Swans, part of an ambient soundscape mixed by the Library's Wildlife Sounds Curator, Cheryl Tipp.”

Santa Claus also gets a mention in the exhibition thanks to 19th century illustrations and political propaganda.

“Canada's Foreign Minister, John Baird, declared Santa to be, 'a Canadian' recently,” says Hatfield.

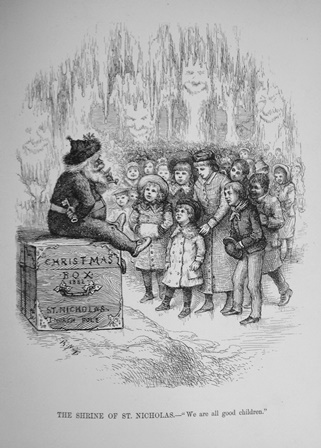

An illustration of Santa Claus by Thomas Nast

“This got me thinking about why some people think Santa is resident at the North Pole and so I had a dig through the collections.

“Fascinatingly it seems Santa's residency there (as well as his contemporary look) is in part thanks to a 19th century American cartoonist, Thomas Nast, who appropriated Santa as a symbol of support for Union forces during the American Civil War and came up with the North Pole idea during the search for Franklin (in which American ships were involved).

“So what we see is a long history of Santa getting caught up in metropolitan politics, as well as delivering presents to children.”

Lines in the Ice runs until 29 March and there will be three events running concurrently with the show.

Back to top