I was extremely flattered to be invited to speak at the South West Federation of Museums & Galleries one day conference on environmental sustainability earlier this month. This is a big topic for museums because it is a key requirement for their accreditation. (Defining good practice, accreditation is the standard for museums and art galleries in the UK.) Examples of how to reduce energy in museums, along with examples of working with visitors to engage with sustainability were discussed on the day.

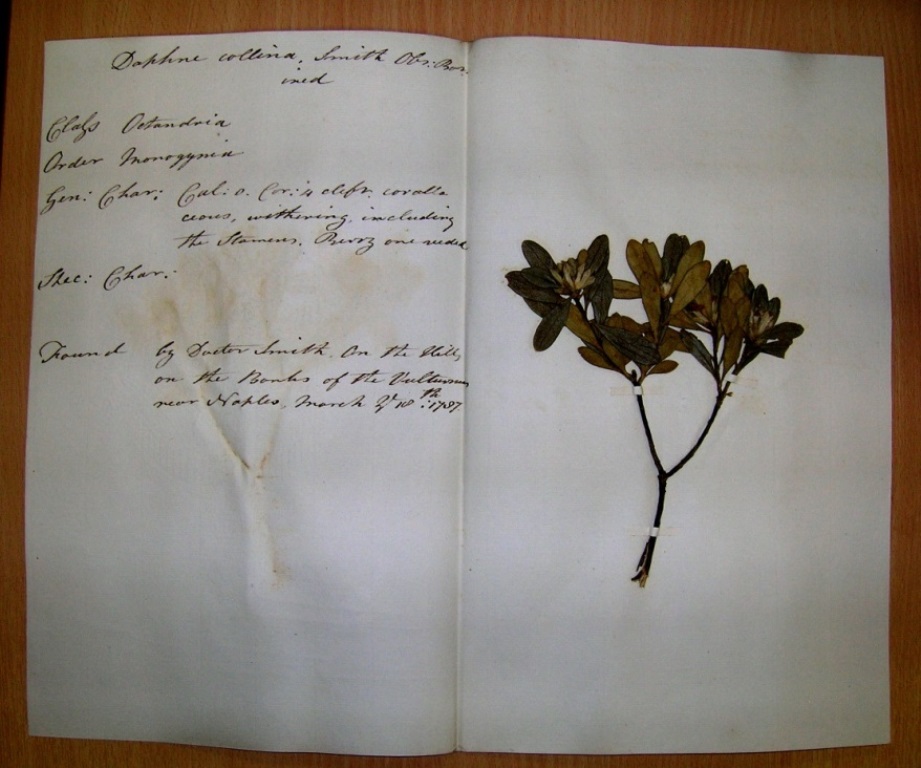

My talk ‘Bring out your dead’ focused on the collections and how they can contribute to current research into environmental issues. What is wonderful about natural history collections is that (in most cases) they have information with the specimens. We are able to see when they were collected, where from, who collected them and sometime other bits of information. A specimen with this information is a record of when that individual was alive, be it 10 years ago or 100 years ago. A beetle without a label is just a beetle, but with a label, we can open a door to the past.

There are many examples of using museum collections for environmental research. Probably the most often quoted study by museum curators was back in the late 1990s which used hundreds of eggs from Thrushes. Measuring the egg shell thickness in museum collections allowed the researchers to show that they got thinner over time. The thinning wasn’t directly caused by pollutants (like the pesticide DDT) in the environment, but may have been due to the pollutants effect on the thrushes prey (reducing the calcium intake resulting in a knock on effect to egg development).

A recent study used natural history collections in museums for a fascinating look at the peppered moth. This little lepidopteran is an icon of adaptation in modern times. The original lighter coloured moth was common in the countryside, where their light colour blended in well with lichen camouflaging them from predators. Darker variations were more common in cities where pollution clung to trees and the lighter coloured individuals were picked off easier. In 2011, some very funky research was carried out. Using just one leg from a myriad of museum specimens, the researchers were able to genetically map the darker variations. Instead of several separate mutations over the country, the darker moths were a result of just one mutation, and this spread across the UK.

In America, researchers used specimen information to model potential changes in the distribution of the brown recluse spider as a result of climate change. The National Oceanography Centre in Southampton holds thousands of spirit preserved marine specimens from the Southern Oceans and North Atlantic. These wonderful collections have been used in many studies in climate change, because they are a record of not just the diversity of species over the last 50 years, but also individuals within populations. There are dozens of other examples. Collections have so much potential use for researchers.

With more than 400 museums in the South West, this region has the largest concentration of museums in the UK. What’s more, over half of these museums hold natural history collections. One of the biggest challenges is letting researchers know that these collections are there.

There are ways of bringing out our dead. The National Biodiversity Network Gateway is a huge database of records of species from all across the UK. Museum specimens can be added to this database. Adding information can appear insurmountable: with tens of thousands of specimens in a collections, there is an awful lot of data. Some museums, like The MacManus, are overcoming this by working it into grant proposals so that slowly, more and more information is added.

A crowd-sourcing project, Natural History Near You, was developed by the Natural Science Collections Association (NatSCA). I wrote about this project in more detail in a previous blog post, but simply put, here is where museums can add the types of natural history collections they hold. If a researcher is looking for museums that study skins, this map will bring up those that do. A neat idea and a first stop for researchers.

Simple touches by museums can easily promote their collections to a large audience. Websites and online databases are the most common ways of the moment. Although this doesn’t guarantee that a museum with a particular specimen will be found, as article by Mark Carnall at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History described a few years ago in an article: if that collection, or that specimen isn’t on your website, internet searches will not pick it up so people don’t know it is there.

I have written about the importance of social media for museum curators, but its power is worth highlighting again. Museum curators are very active on Twitter, sharing specimens normally hidden behind closed doors, engaging with enquiries, and linking work other museums are doing. As well as staying in touch with colleagues I may see once a year, I have been lucky enough to make new contacts through Twitter. It is a wonderful community which opens up new opportunities instantaneously.

There is an awful lot of potential for researchers to use natural history collections in museums. Letting people know what we have seems like it should be simple. Museum curators know about the wonderful stories in the back rooms, but we are surprised when we find out other people don’t. Museums cannot sit on their collections. The collections may be dead, but they are alive with potential and possibilities. If we don’t bring out our dead, they will lay buried.