Recently, an elderly gentleman came up to me and told me I was doing museum labels “all wrong”. I had just finished presenting a talk about the benefits of blogging for science communication. Naturally the talk included lots of tips on how to write effectively for your audience, with examples from my several years’ experience of writing museum labels.

This chap strongly disagreed with my “fun” style of label writing and advocated for more facts on the labels. He wanted more information and more detail about things he is familiar with.

Bear with me while I break this down a little, as I feel he missed the point.

One of the main way museums communicate to their visitors is through the labels that are included in their displays. There are special events, tours, talks and other activities that involve museum staff talking to the public but these don’t happen all the time, in all the galleries, for all the visitors. A label next to an object is often all we have. That’s it. No recorded message or staff member standing next to each object talking about it. Just a small number of words on paper, card or vinyl.

Here’s the tricky bit: the museum visitor could be anyone. It could be a six-year-old kid, a tourist, a specialist, an OAP, or a student. Museum audiences include an enormous diversity of individuals. All who have a different level of knowledge which makes label writing even more complex. So how do we make sure that the labels next to the objects are accessible to everyone?

Great text

It’s all about good text. Great text in fact. And I am very passionate about great text. There is nothing worse than reading a museum label and not understanding bits of it, or if the flow is all wrong. It turns me off. I feel stupid for not knowing the technical words. I end up being frustrated and I move on. Museum labels should be accessible to all, not to just a small elite. Surely there is no greater joy for a curator than seeing all visitors finding out more about that object on display?

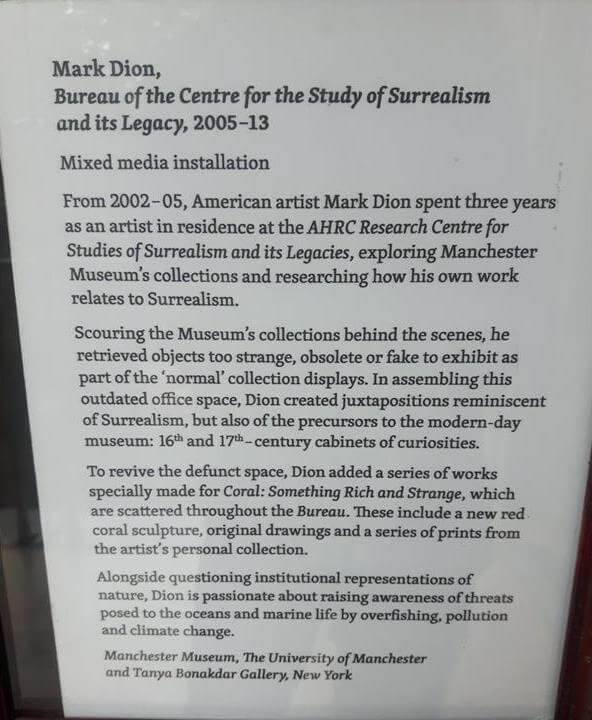

That label next to the object is the only way of bringing it alive. It is the chance for the curator to ‘speak’ to the visitor. To share the passion they have for that object. If done right, the visitor will see that passion and be engaged with an otherwise static thing behind glass. However, writing labels for displays isn’t easy. The curator’s individual writing-style may be more fact focused. The curator may like their own style and assume this is what the general museum visitor wants. Writing for a general audience can be extremely challenging.

According to the National Literary Trust, the average reading age of people in Britain is well below that of an 11-year-old. (To make this a bit clearer, the reading age for the Guardian is 14-years-old, and the reading age for The Sun is eight-years-old.) This means that museums should be aiming to write their text so an 11-year-old can understand it. This sounds pretty shocking. In many respects, it is – but it also gives us an interesting style guide to follow.

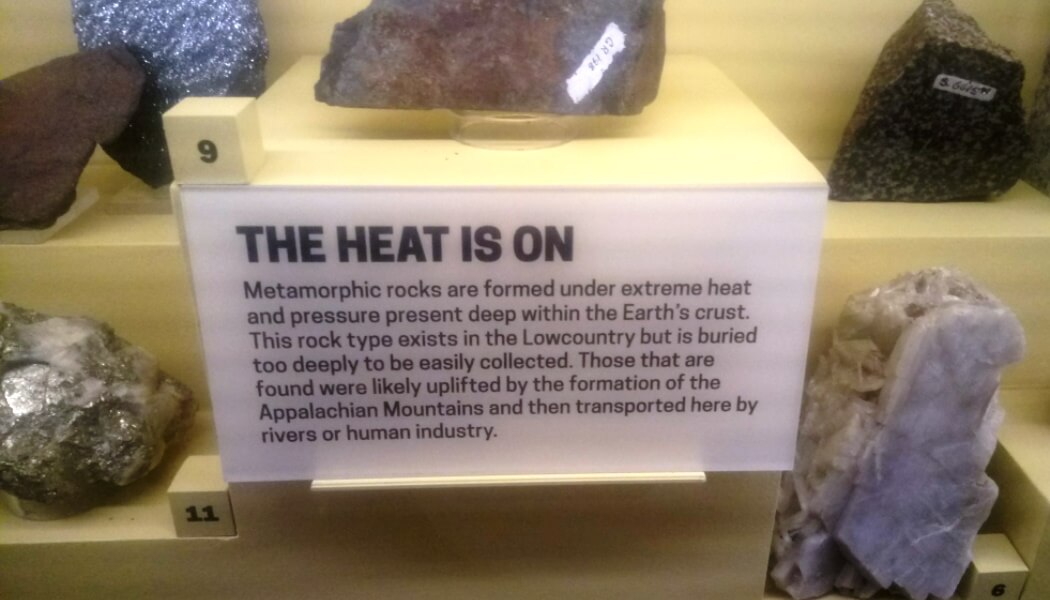

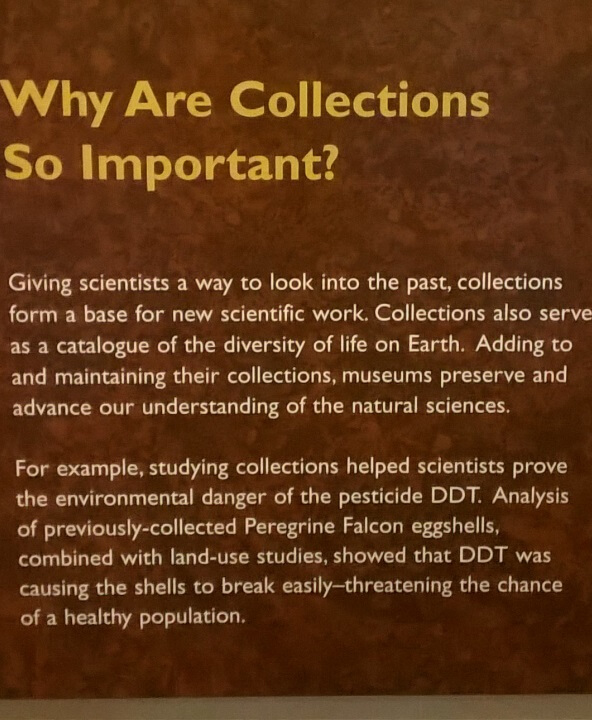

An object in a display case by itself isn’t enough. A title and a date next to that object isn’t enough either. Visitors want to know about that object. Why is it so important? Why is it relevant to them? What is the story? Curators know how amazing this object on display is. They know the facts, the history, and the science behind it. They could easily write dozens of lines, full of all this wonderful knowledge swirling around in their heads. The difficult bit is cutting it down, keeping the interesting facts, and making the label sexy. Yes. Sexy. A curator knows how sexy and incredible an object is, and the greatest joy for any curator is knowing a visitor can learn that too.

Conversational style

Be it a cup or a beetle, great text can make that cup more than just a cup, or that beetle much more than just a beetle. An interesting hook in the first line will make the visitor want to read on. A mix of short and long sentences makes the label flow much better. Quirky facts bring it to life. Stories make the object relevant. A conversational style of writing makes the label easier to digest. The words we choose can make this short 60-or-so word label much more interesting to a much larger number of people. And if it is fun, the visitor will remember the facts. Facts can be written in a fun way, in a gross way, or in a humorous way. There is nothing wrong with introducing a little fun to our label writing.

Let me get one thing clear: writing a fun, engaging label for an object is not dumbing down. It is simply rewording the information in a clear way so that practically anyone can understand it. Labels written in an engaging way can still include the facts, but they don’t just need to be listed one after another. We can write the facts into a story, in an active engaging voice for the visitor. Technical words can still be included in labels, as long as they are explained. This is not dumbing down: the facts are still there, only more cleverly written. Dumbing down and making things accessible to your audience are two completely different things.

Inclusive

Obviously with such a huge audience variety, not everyone will like conversational labels. The majority will though. The majority are not experts and being conversational in a label is more informal for them. I think this is one of the main points: not everyone knows something about the background to that object. Being more conversational is not being inclusive to a small particular audience. It allows those who know very little to get excited and learn something new.

Some of the topics museums deal with are complex, some are sensitive. The tone of the label is important. The tone can convey sensitivity and speak to the visitor. The tone of different galleries may vary slightly, but they should still be engaging, accessible, and be able to really bring that object to life.

Museums have a responsibility to be inclusive. We are open to all. What’s more, we have truly amazing collections that we want to shout about. There is nothing worse than seeing a fantastic display with dull, dry labels that look like they were written decades ago.

For me, if a visitor smiles reading a label, that means they have understood the message within. They will talk about it and hopefully they will leave wanting to find out more. Let’s break the mould. Let’s be adventurous. Let’s make the labels speak with the passion we have for our collections.