On 15 December Tim Peake will become Britain’s first European Space Agency astronaut in space when he launches from Kazakhstan to meet the crew on the International Space Station (ISS). He will join a long list of distinguished men and women, which now numbers more than 500, who have left the earth’s atmosphere for the zero-gravity, weightlessness of space.

These include Yuri Gagarin, a Russian Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who became the first man in space in 1961 and Valentina Tereshkova the first ever woman in space two years later. And Peake will have the pioneering spirit and bravery of these Russian trailblazers to thank for his mission, as well as the fact there is an International Space Station at all.

But how did this happen and why was the first human to make this perilous journey into space Russian? Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age is an exhibition that explains this perfectly. Away from the hustle and bustle of the of the Science Museum’s atrium, the exhibition on the first floor is a calm and clinical show that gives the visitor a chance to soak up the incredible 150-strong collection of objects.

It begins by looking back 100 years to Suprematism, a revolutionary art movement with works by Ilya Chashnik that still look futuristic today and the artwork of Gorgy Krutikov’s Future City (1928), imagining the future of airline transportation and more significantly, the work of one of the fathers of rocketry and cosmonautics, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. The latter’s Album of Cosmic Journeys (1932-33) depicts a cosmonaut exiting a rocket via an airlock. These works show that decades before the Russian’s were sending rockets into space the idea of space travel had already transcended its art and philosophy.

Then we are introduced to Sergei Korolev who went from Gulag to become ‘Chief Designer’ of the rockets that would send man in to space, with his prison mug, coat and hat on display. Under his tutelage Russia entered the Space Race and was to break many firsts: it sent the first satellite in space (1957), the first animal in orbit (1957) the first man in space (1961) as well as the first spacewalk (1965). In 1957 Kurolev said, quite rightly: ‘The Road to the Stars is Open’.

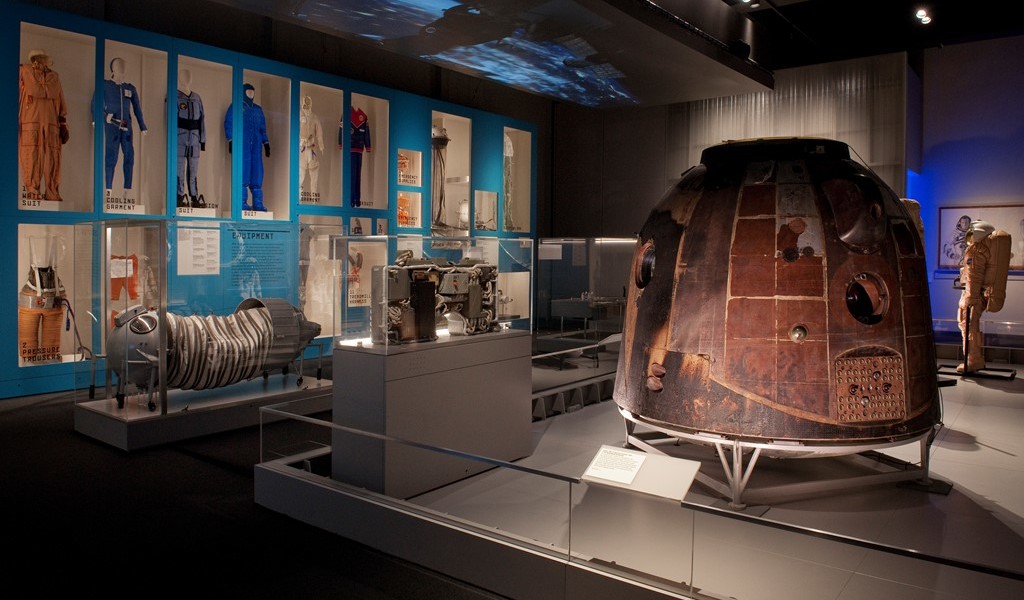

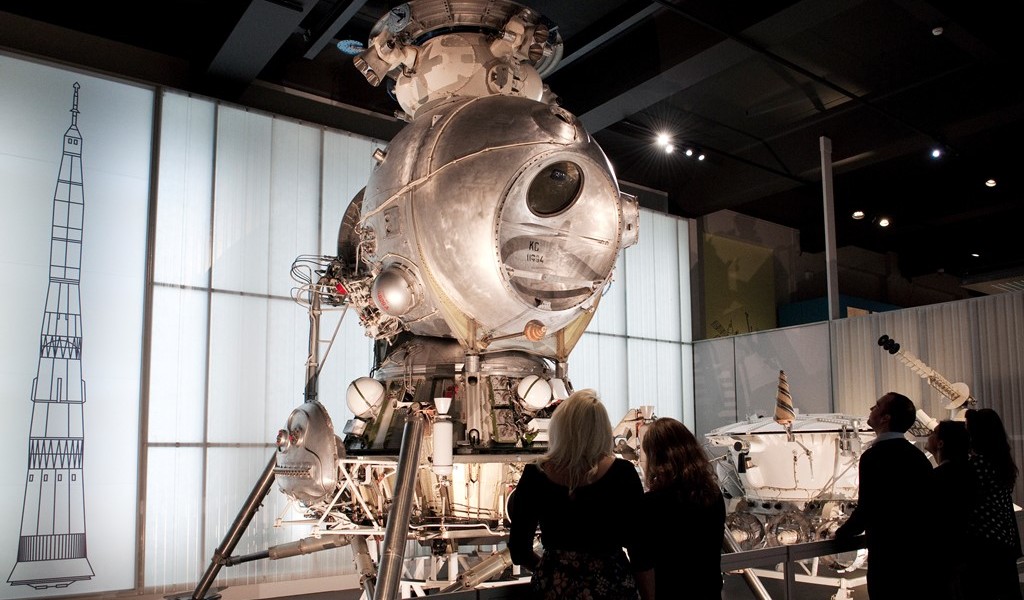

On display are the Vostok 6: the capsule flown by Valentina Tereshkova, the first ever woman in space; Voskhod 1: the capsule used on the first mission to carry more than one crew member; LK-3 Lunar Lander: a single cosmonaut craft built to compete with Apollo, a collection of gadgets that cosmonauts – and pioneering space dogs – need to live in space, including medical instruments and survival kits for crash landings.

Each of these dazzling exhibits are given the space to shine with crisply designed, but not overpowering graphics, offering a balanced backdrop. There is also literature on display from the late ‘50s with a Time magazine front cover splashing the picture of Soviet President Khrushchev as its ‘Man of the Year’ highlighting how the frenzy of space travel had gone beyond Cold War politics to become a human celebration. However, as a Russian medical student’s laboratory coat, with the words ‘Space is Ours’ painted in red on it shows, national rivalry was a major driver and never far away.

As the exhibition snakes around to its finale, it is revealed that Russia had its own Lunar programme that failed to beat the Americans in putting a man on the moon. But not to be outdone the Russians turned their attention to building a permanent outpost in space, which started off as the Mir Space Station (1986) and has since transformed into the ISS. On display are the remarkable if mundane furniture of the Mir including a dining table, refrigerator, toilet and shower.

Towards the end of the exhibition are beautiful displays of cosmonaut suits, which in fact look like enlarged toy figures still in their boxes that have never been opened, including a water suit; a therma suit; a compression suit and a G-force suit. Opposite these is an Orlan Mars 500 extravehicular activity suite, designed for use on the surface of the red planet, which highlights the Russian’s, and the world’s, ever expanding dreams to one day colonise another planet.

This is summed up by a quote by Tsiolkovsky from 1911, which completes the exhibition’s story so well: “The Earth is the cradle of humanity, but mankind cannot stay in the cradle forever,” which at the time must have seemed fanciful, but now, because of the Cosmonauts Herculean efforts, is no longer beyond the realms of possibility.

Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age runs until 13 March 2016.

Main Image

The first man in space. Boris Staris, The fairy tale became truth, 1961. Published by The Young Guard (Molodaya Gvardia), c. Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics