The argument that cultural institutions have a responsibility to blaze a trail for diversity and inclusivity is well-versed in the sector. This sentiment has been perfectly demonstrated by Arts Council England, with the organisation having debuted several new policies of late which ramp up progress in the fields of recruitment and employment.

According to government figures cited by ACE, a third of unemployed people in the UK have a criminal record. It labels this a “depressing fact” and claims it is even more miserable given that gaining employment is said to directly correlate to lowering levels of reoffending.

“Often, the stigma of a criminal record, which follows you through life, is worse than the original punishment,” notes Chris Stacey, Director of the charity Unlock. ACE is seeking to end this prolonged penance by removing from its application forms the tick-box that requires people to declare whether they have any criminal convictions.

It’s very much a journey and policy makers need to understand that – it’s a pretty complex journey.

Banning the box, it is hoped, will remove what Mags Patten brands a “crude, blanket measure” and therefore stop talented individuals being alienated from applying for certain roles.

Discussing how the ‘ban the box’ rethink occurred, she explained: “It came out of our thinking around diversity and inclusion, and the recognition that we as the Arts Council needed to do more for ourselves in terms of our recruitment policies and how we look after people in the organisation.”

In what appears a common occurrence for employers, ACE discovered that while it had never intentionally deterred those with a previous criminal conviction from applying for work its recruitment literature had done precisely that.

“We weren’t consciously discriminating against people who have had experience of the criminal justice system, but you have as an organisation to actively think about what you can positively do to remove barriers,” Patten told Advisor. “Partly it’s just the right thing to do. Also we have a leadership role in the cultural sector so I think it’s important that we as an organisation are doing all we can. That gives us more moral authority, if you like, to encourage others to adopt similar policies.”

Art behind bars

Patten is, however, in no way naïve enough to think that simply removing a tick-box is the answer to the employment challenges facing individuals with a criminal record.

ACE channels around £900,000 per year into organisations across its national portfolio that work as specialists inside the prison environment. “This is an important part of what we do,” the Executive Director of Public Policy and Communication noted. “The technical term for becoming crime free is ‘desistant’. It’s very much a journey and policy makers need to understand that journey – it’s a pretty complex journey.”

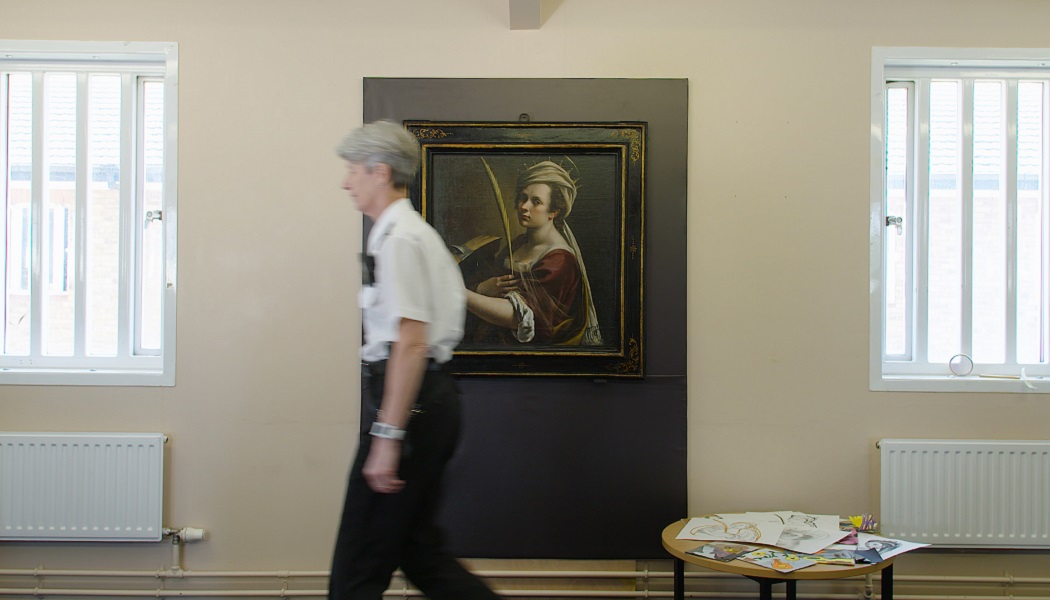

Outlining where the sector is getting it right, she points to artist-in-residence schemes in various prisons alongside the work Watts Gallery has done with HMP Send. In order to enable prisoners to “engage with objects,” Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria by Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi went on display at HMP Send this year; the first time an artwork from a UK national collection was displayed in a prison. This occurred alongside the institution’s wide-ranging work in partnership with the National Criminal Justice Arts Alliance.

This focus is “inspired by the Art for All community art practice of Mary Seton Watts in the 19th century, that offered art and craft education and enterprise to support people’s rehabilitation from poverty, illness, isolation, unemployment and crime,” according to Kara Wescombe Blackman, Head of Public Programmes, Learning & Visitor Services at Watts Gallery.

Over three days in May a National Gallery artist educator delivered workshops for up to thirty women prisoners. The sessions were conducted in front of the aforementioned painting and comprised learning about both the artist and the painting, as well as taking part in a range of creative exercises. The gallery also donated books to the institution as part of the project which drew widespread acclaim for its approach.

“Going into employment is a vital element of ensuring people make good choices and avoid engaging with crime,” Patten concluded. “We can be bold in our vision about what we want to achieve. There is excellent work going on but there’s so much more we can do.”

A clear difference

Use of the new Recruitment and Workforce Development Toolkit from ACE and Clear Company will be encouraged among all Arts Council funded bodies, but sign-up will also be freely available for all arts and cultural organisations – regardless of size and current policies.

Abid Hussain, Director of Diversity at Arts Council England, referenced how the organisation is aiming to “fully reflect the communities they serve; recruiting, retaining and providing career development pathways for diverse talent and fostering inclusive workplaces is a significant part of achieving this aim”. This is an approach he hopes to see adopted throughout the cultural sector.

The resource has been built so that the software integrates initiatives into day-to-day processes, ensuring efforts are spent on activity with proven benefit while avoiding the creation of additional work.

Jen Davidson, Managing Consultant and Lead of Clear Assured, stated that the toolkit represents “a serious commitment to a diverse, innovative arts and cultural sector”. This is achieved, she claims, by “enabling each organisation to choose their own journey it provides bespoke direction and support for busy teams leading to consistent progress and achievement”.