Set within the spacious new Sainsbury Exhibition Gallery of the British Museum Celts: Art and Identity was designed by Real Studios and takes reference from more than 250 objects from the Iron Age, Roman and Early Medieval periods made for feasting, religious ceremonies, adornment and warfare.

Rather than a show about a specific people or group isolated in space and time, Celts: Art and Identity is an exhibition that explores the evolution and re-invention of an idea spanning 2,500 years. The recent revelation that ‘the Celts’ are not a single genetic group has given the Celts: Art and Identity an extra relevance as it investigates this shared cultural heritage and why the term still carries such a powerful resonance today.

The term Celtic is now understood as a cultural label rather than an ethnic identity says the British Museum, and tracing its roots to 500BC, Celts: Art and Identity is able to tell the story of how the word was used by the ancient Greeks as a broad label for barbarians to the north and was subsequently adopted by the peoples of the modern Celtic nations to emphasis their distinctiveness.

“The idea was to curate an exhibition which would reflect the growing body of academic work which challenges the idea of the Celts as a single people,” says curator Julia Farley. “We aim to tell the story of how the word ‘Celts’ has been reinvented and redefined over the last 2,500 years, looking at the similarities and differences between the different peoples who have used or been given this name.”

There are 267 objects in the show with 110 from the British Museum’s collection, 47 loan objects from National Museums Scotland, 17 further UK lenders lending a total of 50 objects, and 10 international lenders lending a total of 60 objects. The majority of these are joint loans shared with National Museums Scotland.

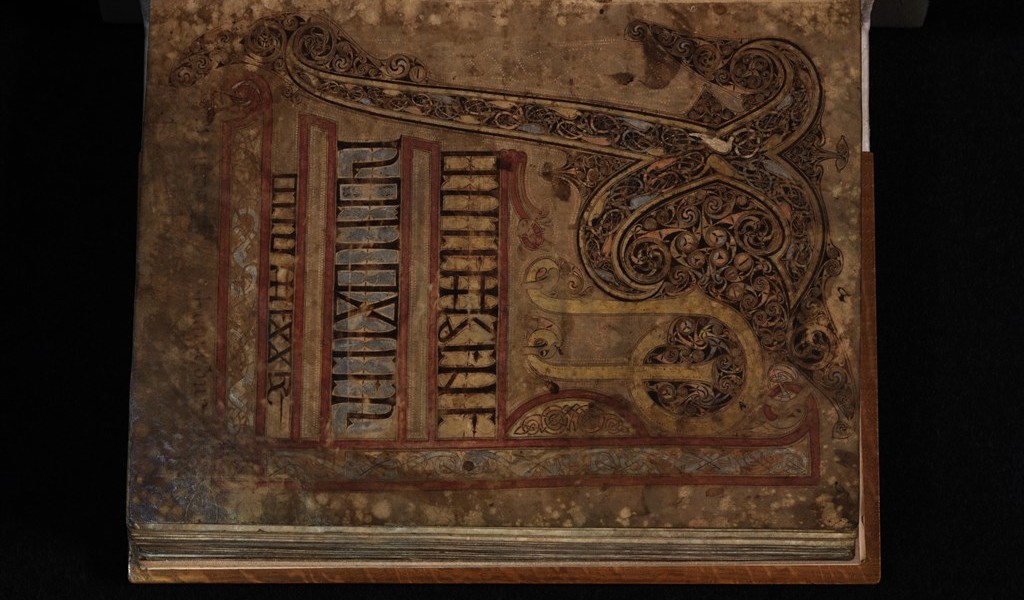

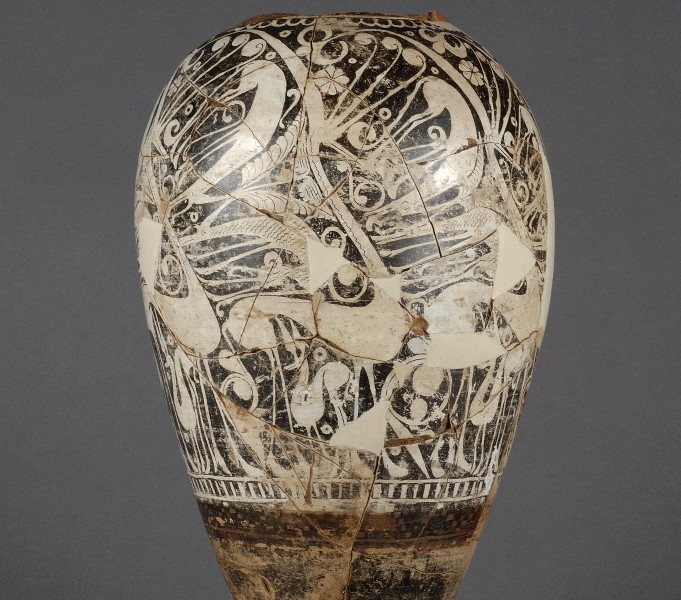

Star loans include the imposing, horned Iron Age statue from Holzgerlingen in Germany, the Gundestrup cauldron from Denmark, painted vases from Clermont-Ferrand in France, the illuminated St Chad gospels from Lichfield Cathedral, the painting ‘Druids bringing in the mistletoe’ by Henry and Hornel, and the archdruid’s ceremonial regalia from the Welsh Eisteddfod.

The show was first proposed in 2003 and since then the concept has evolved, becoming a project organised in partnership with National Museums Scotland. Because the exhibition spans two-and-a-half millennia, and encompasses much of Europe, the potential scope is vast, which meant that it was essential for the curatorial team to prioritise loans, which allowed them to present a complex (and perhaps unexpected) story through these objects, dealing with both prehistoric and contemporary material, and everything in between.

“This meant treading a careful balance between stunning art objects and objects which help us to carry a complex narrative in an engaging way,” says Farley.

The team wanted to make the abstract designs of Celtic art more accessible to the general public by providing ways to engage with the sometime mystifying imagery on these objects. Farley says that this complex, shape-shifting art is one of the threads which runs through the whole exhibition, and through the choice of objects and the design surrounding them the exhibition provides visitors with the opportunity to appreciate and understand this rich northern European tradition of non-classical art.

“We hope that this exhibition will challenge some widely held assumptions about the Celts, and firmly establish in the public consciousness the idea that ‘Celts’ is a word which has taken on a new meaning over the last few hundred years,” says Farley. “Rather than an isolated ‘Celtic fringe’, the show reveals connections across Europe over thousands of years, and a richly inventive artistic tradition which was continually changing and drawing on new influences.”

The British Museum says that it is essential for museums to engage with themes such as the Celts, which have a contemporary social and political relevance, to explore how our understanding of the past informs who we are today. Celts is a word that still resonates in the modern era, largely, says Farley, because it has always been a fluid term that is capable of being read and understood in different ways. “For this very reason, it remains an important aspect of many people’s identities, even if the meaning it carries now is very different to the one it held 2,500 years ago.”

The exhibition also explores recent scientific analysis of Iron Age torcs, from Snettisham in Norfolk and Blair Drummond near Stirling. These studies have revealed connections across Europe 2,000 years ago and an incredible degree of technological skill and expertise among the craft-workers of ancient Britain ‘which stand on a par with the finest achievements of the ancient Greeks and Romans’. Celts: Art and Identity also presents genetic research published in 2015 which suggests that there is no single ‘Celtic’ genetic group.

For example the populations of Scotland, Cornwall, Wales and Northern Ireland showed great genetic diversity reflecting their distinct local and regional histories. These findings support archaeological and historical research suggesting that the Celts are not a single people who can be traced through time. Celtic identities are cultural rather than genetic or racial, and the meaning of the name ‘Celts’ has shifted over the last 2,500 years.

As part of the National Programme activity around the Celts exhibition, the British Museum and National Museums Scotland have also worked together to create a touring ‘Spotlight’ loan which showcases two rare Iron Age mirrors at partner museums across the UK.

In order to maximise the importance of the objects exhibition designers Real Studios created a curving spine wall that splits the gallery along its length, drawing visitors along its sweeping form to a magnificent 4m high Celtic cross at the end of the gallery. The wall’s curves create natural alcoves and enclosures which provide opportunities both to hone in on the smaller artefacts – jewellery (pin brooches, torques and rings), weapons and figurines – and also frame the larger items including stone carvings, statues and paintings. “The organic forms are designed to complement the content, carrying visitors through the space and offering a strong focus for the artefacts, while maximising opportunities to enjoy the exhibition’s generous volumes and vistas,” says Real Studios director Alistair McCaw.

A key challenge for Real Studios was the 6m high ceilings, which risked overwhelming the majority of small objects on display. Their solution was to devise a sculptural hanging voile that reflected the Celtic motifs taken from the artefacts and filled the upper volume of the space to bring both a feeling of intimacy and decoration.

“The majority of early artefacts are metal or stone, so the design has incorporated softer, more organic materials into the setting which are strongly associated with Celtic crafts – such as wood and hides – but which have not survived over the centuries,” says McCaw. “The colour palette changes as the narrative follows the Celtic tribes across Europe (greens and reds) to their stronghold, in Scotland (a heathery purple).”

Audio Visual presentations at the start and end of the exhibition provide context, with the introductory AV revealing the historical scale and geographic breadth of Celtic heritage, while the concluding AV concentrates on the continuing Celtic influence on national identity.

Celts: Art and Identity runs at the British Museum until 31 January 2016.

Main Image

Queen Mary’s harp, National Museums Scotland. National Eisteddford banner, Gorsedd of the Bards, Wales. Christian-cross slab, Invergowrie, National Museums Scotland. © The Trustees of the British Museum