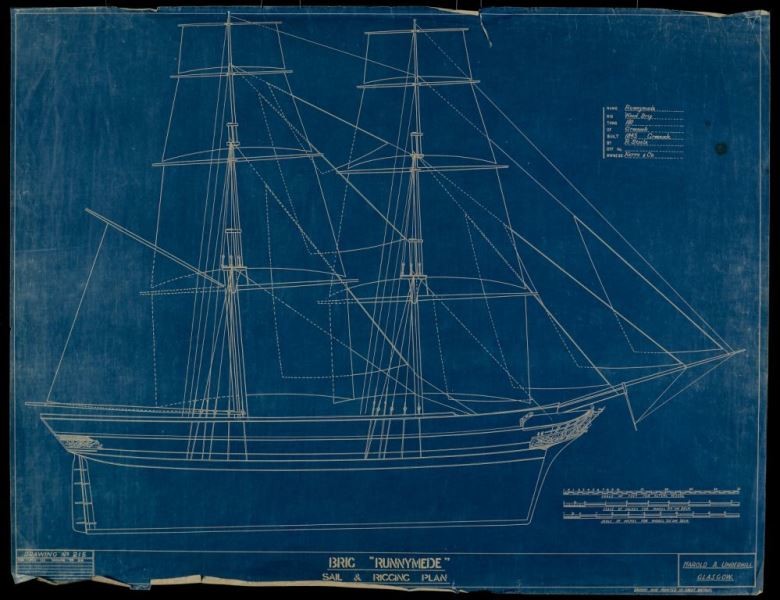

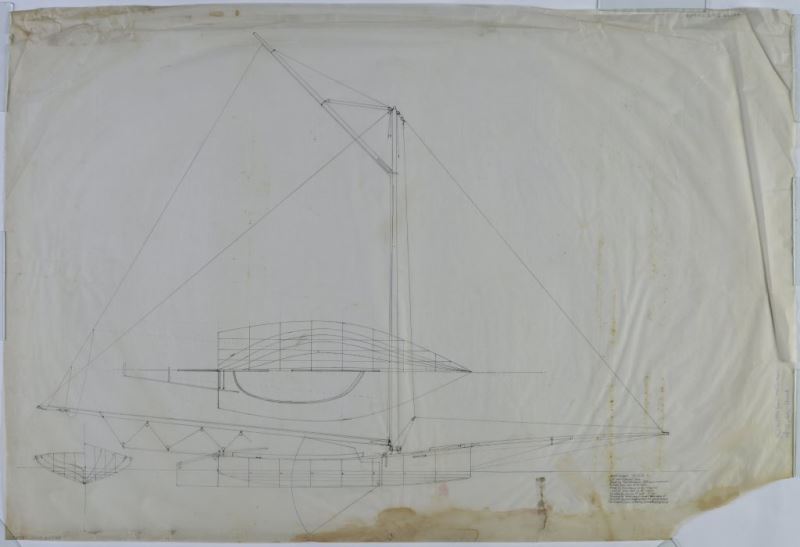

During 2012 and 2013 the Brunel Institute at the ss Great Britain Trust saw the undertaking and completion of a large scale digitisation project of the David MacGregor Ship Plans Collection with more than 6,500 ship plans carefully digitised. The bequest of maritime historian David MacGregor (1925-2003) the ship plans are part of a huge collection comprising of 19th and 20th century photographs, maritime postcards, books and periodicals, paintings and film.

Probably the most important research collection to be transferred to a maritime museum in recent years, the ship plans focus on sailing ships, their history and technological development over the past three hundred years, but also on other types of vessels and the general development of engineering including shipbuilding before and during the Industrial Revolution. The continuity in the collection over MacGregor’s lifetime and its diversity make it of value for contemporary maritime and social history and research hence the significance of its documentation, digitisation and access. The aims of the overall project were to rationalise, catalogue and ultimately digitise the collection in order to make it widely available and ensure access for the general public and for those with specialised interests, but also to share the process along the way.

The first phase of the sorting and documentation project came with the discovery that the ship plans collection was actually almost three times its original estimated size. The physical size and sheer number of the plans presented our team with challenges on handling, storage but also with time and funding constrains. Equally, the range of materials represented in the collection added to the complexity of the project; the majority of the plans are paper (75%), with the remainder being acetate and a smaller number of blueprints, linen, polyester and tracing paper.

However, the collection acted as a catalyst for partnerships and an opportunity to involve external and internal expertise as well as visitor participation. It was important for the Trust and our team to keep the lengthy and testing process of the digitisation open to the public and to share the importance of the plans and the ways in which they were managed, by allowing the public to be a part of this huge undertaking.

We developed a work plan from the very beginning of the project and set targets for documentation after a month’s trial period (300-400 to be processed monthly). Every original plan would be catalogued and digitised, exact duplicates would be excluded. In terms of condition and conservation we accepted that it would not be possible to treat all, but just the very vulnerable historic ship plans from this collection. The digitisation, rehousing and encapsulation would result in all plans being kept safe and that any mechanical damage (tears, folds etc.) would not deteriorate before seeking professional help by a paper conservator on a case by case basis.

Before the project begun our volunteers and staff were trained by accredited paper conservator Caroline Harrison, which meant that all contributors benefited from participating and learning about good museum practise in handling and working with a range of fragile and uncommon materials and printing techniques. We found that this in-house knowledge allowed us to generate ‘train the trainer’ sessions in order to pass on skills learned, while as a result we increased the organisation’s knowledge base and ultimately confidence in this area of collection care. Eventually, this enhanced the visitor experience as visitors to the site observed and learned about good collection practice and behind the scenes work.

The Mobile Scanning Company (MSC), who were contracted to digitise the plans, were hired on the basis of working alongside our volunteers but also engaging with the public during our open doors Archive in Five and Conservation in Action sessions. At these regular sessions items from the collection are given special attention as we offer the opportunity for the public to view and learn more about them in an informal setting. These sessions were an ideal introduction to the ship plans digitisation project and were extended beyond the one hour duration to cover the whole morning from 10:30 to 13:30 in order to offer the opportunity for more visitors to be involved.

Visitors walking into the Institute entered the room where the digitisation was taking place, which had been transformed into a photographic studio complete with black out sheets and studio lights. All handling of the plans was done by the Institute’s volunteers who would move and prepare each plan, which would then be photographed by the Mobile Scanning Company before appearing on a large plasma screen in high definition. Visitors were able to advise on whether an image was sharp enough or needed to be cropped, but also become the photographer; an iPad, remotely connected to the camera was offered to individual visitors and families who were encouraged to press ‘FIRE’ and take the shot. Running parallel to this, volunteers were inviting, welcoming and explaining the importance of the process as it took place in front of them.

The opportunity for visitors to become such an integral part of the digitisation caused great excitement among people of all ages. Not only were they engaging with the collection, but their stay was prolonged as an interest was ignited in the methods, tools, expertise and amount of work that takes place behind the scenes. Often, visitors wanted to know more about the ship depicted on the plan they had just photographed and took great pride and joy to have helped us in our huge task of rationalising and making accessible the thousands of plans in the MacGregor Collection.

Bursts of digitisation activity over 2012 and 2013 allowed us to digitally capture hundreds of ship plans, for a few days at a time, continue with the all-important sorting, documenting and re-housing and complete the work by May 2013. During that time 2103 people viewed and participated in the process over 54 separate Archive in Five and Conservation in Action sessions. (957 people over 30 days for 2012, 1146 people over 24 days for 2013).

We found that keeping targets and recording the progress of the project has been a great motivator for staff and volunteers. This has also improved speed and a shared sense of responsibility, ownership and visibility. Communicating that progress across the organisation has brought collection work to the foreground and raised awareness of the behind the scenes activities to colleagues from other departments, such as finance, fundraising and marketing teams and has demostrated how the funds and publicity they raise are being used and for what purpose.

The Archive in Five and Conservation in Action sessions for the MacGregor ship plans digitisation placed the emphasis on public engagement from the outset of the project and have enhanced the relationships with our users.

Our visitors have been able to participate in making accessible a fascinating and extremely important maritime collection which not only enhances the understanding of the ss Great Britain but has wider value for the study of nineteenth century ship technology.

As we have now begun making the digital images of the plans available we are also building on the experience gained within the organisation for our staff and volunteers. We have a better understanding of the processes, time and resources required for such a big project but also greater confidence in allowing the public to participate. This project also allowed our team to enjoy and share the process, engage with visitors and set a precedent for future collection related activities.

Funding and visitor engagement

Funding was found externally for the documentation, conservation and digitisation element of the project from the Esmee Fairbairn foundation and the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust, while the sorting and visitor engagement planning and operation was done internally with the assistance of Library and collections volunteers. Our team of volunteers and collections staff worked closely with the rest of the organisation in order to prepare and make the ship plans accessible. The public was kept informed via our website, Facebook and Twitter as well as with articles in our members’ magazine, the Gazette.