The Collections Dive at TWAM is an alternative mode of presenting the collections for discovery and although it is not presenting any records online for the first time (objects presented were already digitised and made available by TWAM through its online catalogue) it gives a fresh interpretation to 32,592 objects.

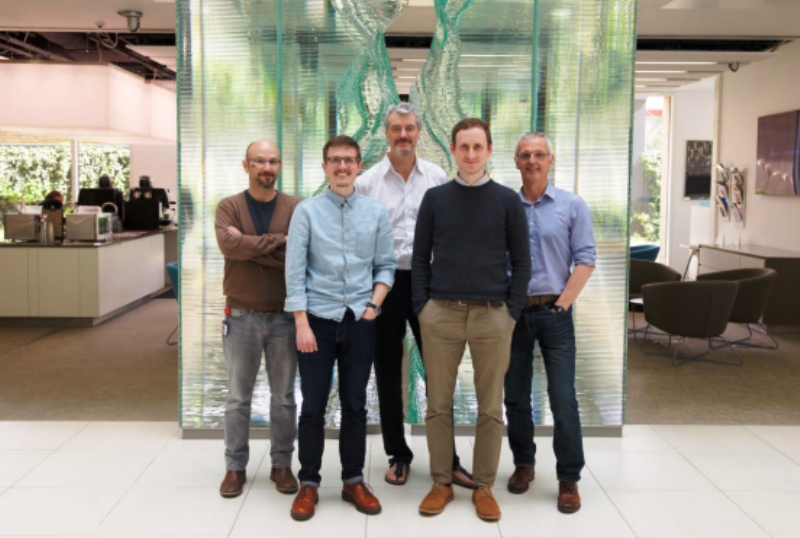

The project, which was launched in the summer of 2014 and completed in September 2015, was the result of Digital R&D for the Arts grant, which required there to be three distinct partners identified for the delivery of the project, which were; Arts, Technology and Research. The research and technical effort was a collaboration between Microsoft Research (MSR) and Newcastle University (NU). TWAM was responsible for overall project management, coordinating the marketing and PR effort and for providing collections data to be used in the System, and The Collections Trust acted as an adviser during the prototyping and testing stage, as well as a bridge to UK museums during the final phase roll out of the System.

A report was subsequently published in October 2015, which gives detailed insight into the project and its findings, which TWAM hopes will be beneficial to the wider sector.

The Collections Dive project found that it was hugely important for museums to create different ways for audiences to use and interpret what was online. Different audiences create different value from museum collections and the majority of the audiences from TWAM’s research were not inclined to use traditional search tools but they were interested in collections.

“Perhaps the most revealing insight was that almost twice as many visitors accessing the collections search pages on TWAM’s websites identified themselves as audiences who don’t know what they’re looking for,” says John Coburn Digital Programmes Manager for Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums. “Regardless of whether the interface satisfied their need or not, the click-through data indicates that a substantial online audience exists that desires collections engagement without a specific search request in mind. The responsibility therefore is with the museum to create user-centric experiences that propel casual, curious audiences into and through the collection.”

They found that a highly visual interface encouraging browse was a successful way of expanding audience engagement with collections. Close to 70% of audiences cited this different presentation as the reason why they enjoyed the experience and discovered surprising artefacts.

There were clear differences between user behaviours, engagements and expectations of what a collections website is for. “The highest proportion of users revelled in the aesthetically interesting and visual pathways through multiple collections, explicitly stating it was what they liked most,” says Coburn. “They enjoyed casually encountering diverse objects at once and stated that they engaged with material they would not have chosen to look for otherwise. A second audience wanted much more control over the experience and to better understand the categorisation and relatedness of objects on display.”

Although there is a fundamental intelligence to the objects’ presentation (not randomness), it was not explicit enough for the second audience who found the aesthetic and immersive experience hindered their primary quest for information and sense making. A third audience enjoyed the novel interaction and discovery of rich material but wanted text search as an eventual part of the experience, once interesting artefacts had been found.

“Collections engagement is all relative. There are those for whom ‘engagement’ is embodied as objects being selected, studied and shared.”

Other engaged audiences, the research found, were happy to spend prolonged periods of time browsing without diving into individual artefacts or socially sharing them. A behavioural distinction can also be made between those who see the interface as merely a tool to get to the object and those for whom the collections interface is a holistic experience, and an encounter with a patchwork of rich data.

Coburn says the sector has done well to accommodate the research audience over the years, which he refers to more than just academic researchers and includes school children, hobbyists, artists, specialists and anyone with an explicit object destination in mind.

“We know that more casual audiences are out there who are simply curious as to what might exist in the collections. They’re receptive to non-traditional, browse based interactions, they can be inspired to share objects or delve much more deeply, and they’re more inclined to give up on online collections experiences more quickly if it does nothing to provoke or intrigue them.”

Conversely, Coburn said, they also know replacing standard text search with more novel browse scenarios does very little for some audiences simply wanting to find the object or the information.

“It’s not about replacing one form of search for another. It’s about easily providing a range of discovery tools for the audiences who do or don’t use collections. This could in designing more user-centric interfaces, or in purely making the collections data more accessible and reusable. It throws up a lot of questions about what collections engagement is and can be. Is it really just about viewing or repurposing an object record? I’d suggest for some of our audiences, the idea of objects and collections is still mildly perplexing.”

Coburn says that museums have long spoken about moving collections interfaces away from object records to storytelling, and differently curating and presenting linkages between artefacts that throw up new patterns of meaning and showcase rich and surprising narratives.

“Ultimately, this all boils down to how good your data is. Sparse object records with low quality images cannot be remedied with a novel interface and we know from previous projects that minimally completed records are just as unlikely to appeal to developers freely accessing them via an API etc. Just because they’re reusable it doesn’t mean them attractive to audiences in the habit of repurposing data. An online collections experience, whether novel or traditional, will succeed or fail as a direct result of the quality of the data it presents.”

Therefore Coburn says that it’s an ongoing challenge to respond to what these behaviours tell us and that it is important to remain keenly aware of the technical and conceptual barriers that collections interface present to our public.

The Collections Dive project has tripled the number of users who engaged with TWAM’s collections through its museum and gallery websites. Additionally, twice as many users engaged with Collections Dive (7,444) than the standard collections interface (3,384) July-Dec 2015. However, we should remember there was marketing for the Dive interface which will have skewed these figures.

However, as this was multi-partner R&D there were numerous challenges, which he says were all healthy and crucial to the development of the eventual outputs.

The design-led research approach to the R&D of the System was a standard development process for both the NU and MSR team but not one familiar to TWAM. Whereas a museum might start the project by generating audience insights and then conceiving a digital development in response, this methodology used a prototype as a tool for continually provoking audiences into reflecting on how the System should work. The cycle of iterations following the first prototype placed fine grained user analysis at the heart of each design decision. “This was very time intensive and the data was often contradictory and complex to react to. However, the process was agreed to be an effective mechanism for making incremental UX improvements to the System.”

The collections data already presented a challenge to the team as cultural heritage object record data is often sparse, with incomplete fields, missing images or minimal information. The richness of TWAM’s data across its half million digital records varied greatly and initially this was a cause for concern in the design team. However, there were a large number of records with high quality images that supported there ambition to create a visually rich browse interface. This resulted in an interface designed to maximise the visual complexity of the collection and therefore play to the data’s strengths.

Since its launch the team have identified a number of design changes, technical improvements and potential expansions of the system that would be considered for a next round of development. These include connecting the front-end interface to a live collections data source; exposing objects to organic search to engage broader online audiences via search engines; and significantly improving mobile functionalities. Despite being mobile responsive and tested on mobile, user feedback identified improvements to be made.

“While this was an experimental R&D project primarily concerned with better understanding audiences and their relationship with collections discovery, it did result in a functioning collections interface that will continue to be maintained and kept live for the foreseeable future,” says Coburn. “TWAM has no in-house web team and subsequently, any technical development will require further funding. TWAM and NU are interested in identifying R&D funding to support a next iteration of the system in response to the insights gleaned to date and to ongoing public usage data.”

In Focus - Digitising Collections

This case study is part of an In Focus feature on Digitising Collections. Click here to see the introduction and links to three more case studies

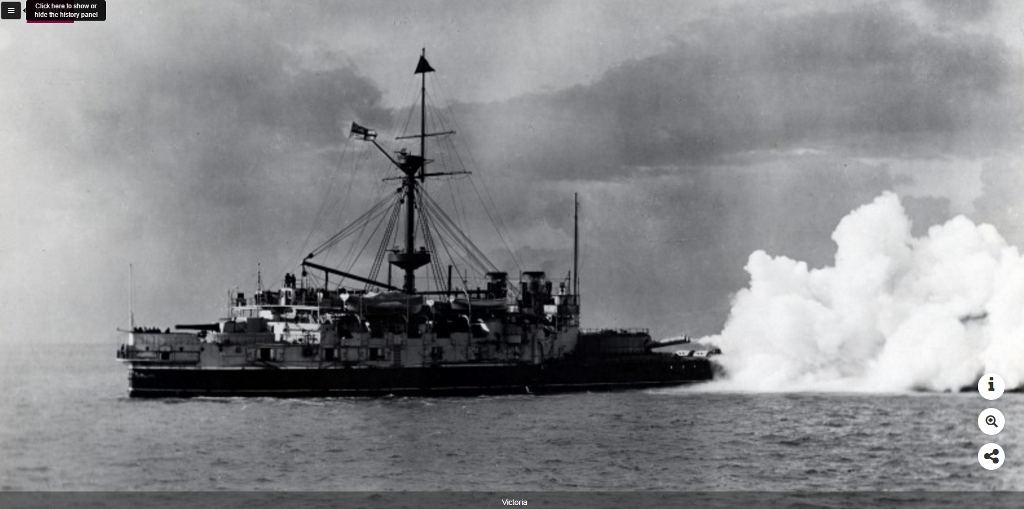

Main Image

Jonah Preaching before Nineveh by John Martin (1789–1854).Hatton Gallery