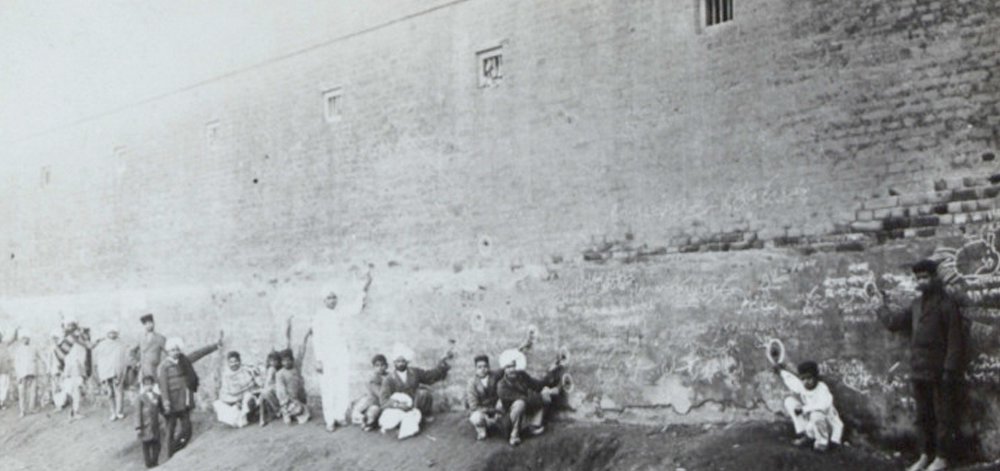

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, which took place on 13 April 1919, is said to be a turning point in the fate of the British Empire after troops of the British Indian Army, under the command of Acting Brig-Gen Reginald Dyer, fired rifles into a crowd of Punjabis who had gathered in Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, Punjab resulting in the recorded deaths of 379 and more than 1,100 injured.

Last month Prime Minister Theresa May stated the British government’s ‘deep regret’ for the massacre calling it a “shameful scar on British Indian history”. However, no formal apology has ever been made.

Now the massacre is being remembered at Manchester Museum in an exhibition that explores how the British came to be in India, what led to the massacre, and its ramifications for the British Empire.

Manchester Museum is currently building a new South Asia Gallery in partnership with the British Museum and its director, Esme Ward received a grant from the British Council to visit India and pursue a youth exchange programme between Bangaluru and Manchester.

However, just before she left in late summer last year she met author, Lady Kishwar Desai at the British Library, who was involved in developing The Partition Museum, which opened in August 2017. Desai, whose books include, Jallianwala Bagh, 1919: The Real Story on which the exhibition is based, told Ward to visit the museum in Amritsar and see the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre displays.

“And of course, when she said it, I knew that this would be something we could explore as Manchester is commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre this year and Jallianwala Bagh happened 100 years later in 1919,” says Ward.

“I was thinking how museums in the UK could build different relationships with museums internationally and what that looks like. Often this revolves around a touring exhibition or an international exchange programme, but that’s only individuals, that’s not building a relationship between museums. So I travelled to Amritsar to visit the Partition Museum and meet the people there and will now build a partnership for the longer term, in relation to our new South Asia Gallery, which will open in 2021.”

But she says they couldn’t just take the show as it was in Amritsar to Manchester as much of it was about being in that place and being able to visit the garden and memorial.

This led to the idea of a six-month co-curation of a new version of the exhibition that would be facilitated via Skype. Ward says that both Manchester and Amritsar are two cities deeply affected by colonialism in very different ways and this was a chance to show a global perspective rarely explored.

As a sector, Ward says museums are extraordinary well placed to do this work. “Very early on I was thinking about the skills we needed to curate this exhibition and I asked someone who had never curated a major show before but who is an educator and extremely good at collaborations and public engagement.”

She chose Catherine Lumb, who has spent her career working on programmes with secondary school children to understand some of the ethics and issues around museum collections.

Lumb was introduced over Skype to Priyanka Seshadri, The Partition Museum’s Museum Associate for Curation, in late November and the two of them had regular online meetings.

“This was a real challenge but an exciting one – international partnerships can be difficult –and I was concerned about not being able to go over there before the exhibition and see everything and meet people was going to be a barrier, but it actually hasn’t been,” she says.

Lumb says that all The Partition Museum exhibition text was put into Google Drive and her and Seshadri were able to edit and make live comments and save changes. The space at Manchester Museum is smaller than its Amritsar counterpart, which means that they condensed the text from more than 5,000 words to 1,500.

“All of the content the Partition Museum had we went through week-by-week, section-by-section. Pryanka put all of the photography and images and audio visual content for each of the sections on Google Drive. We decided which bits were vital, which we could lose and which bits we could condense and reedit.”

Manchester Museum has also been able to use The Partition Museum’s witness accounts from the Disorders Inquiry Committee report on the massacre. Some of those accounts have been recorded in Hindi by The Partition Museum and are played in the background of the exhibition. They have also used interviews from descendant that will be played on screen, which have been subtitled into English by The Partition Museum.

“We also have versions of some of the court lines read out by actors from Dyer’s interview, where he tries to explain some of the rationale for why he decided to do what he did.

The exhibition, says Lumb, is a capsule of what is on show at The Partition Museum and they are hoping to digitally support the content so visitors will have access to the wider resources.

“I think when the international collaboration was first mentioned I found it quite intimidating but myself and Pryanka found it a lot easier than we thought it would be,” said Lumb. “Skype has been a fantastic resource and being able to have conversations, as much as the telephone is a fab invention, and being able to see each other’s faces and talk face-to-face has been far more beneficial and it something that we will utilise a lot more in the future.”

Leading up to the launch of Jallianwala Bagh 1919: Punjab under Siege exhibition on 11 April, Lumb also conducted a video conference with Seshadri’s team and her own visitor team so they would feel confident talking about the exhibition’s content.

“So, it has been a really enlightening experience seeing the possibilities of this process. Obviously there are a few things we learnt along the way with regards to being very clear about deadlines, especially given the time difference. And also that we gave each other enough time to respond to requests. I think on the whole this is going to encourage us to do more partnerships like this and I would encourage other museum colleagues to not be afraid of developing their own partnership in this way.”

Manchester Museum has supplemented its exhibition with loans from its partner museums. It has loaned a Lee-Enfield Rifle from the Fusiliers Museum in Bury, which is the same type of rifle used in the massacre, textiles from the Whitworth which highlight the cotton trade and one in a series of five Empire Marketing Board posters from Manchester Art Gallery, highlighting the tea trade.

There are also botany samples from its own collection that help explain why Britain was in India. The museum has also collaborated with the Singh Twins to create a new large-scale artwork for the exhibition depicting the massacre. Manchester musician, Aziz Ibrahim has also created a new piece of music in response to the tragedy.

A larger partnership within the UK has also been created with smaller versions of the exhibition being displayed at the Library of Birmingham and the Nehru Centre in London.

And a legacy of the exhibition will be the museum’s new relationships with its community, including work with gurdwaras in the area, which has involved recording the stories of descendants of those individuals who were present at Jallianwala Bagh, which will be shared with The Partition Museum.

“I love the way this partnership and exhibition has given us a different lens to look at our collection,” says Ward. “For me there is a lot of talk about decolonising museums and about restitution but the conversations regarding restitution are often framed in legal language around ownership, and what I’m interested in is how we can be more relational. How do we shift this to be thinking about our relationships? And for me that means our relationships with museums and with people in India.”

Jallianwala Bagh 1919: Punjab under Siege will have a closing ceremony on 2 October, a date that marks the 150th anniversary of Gandhi’s birth and it is hoped that following this, parts of the exhibition will find a permanent home in some of the local gurdwaras.