As the UK general election campaign dominated by Brexit talk nears crescendo, the argument is often made that the NHS and other public services will be unable to cope without staff from all over the world. Based on the figures this argument is nigh impossible to refute, and the same principle applies to the passionate, dedicated and boundlessly knowledgeable volunteers on which the nation’s cultural and heritage sectors are built.

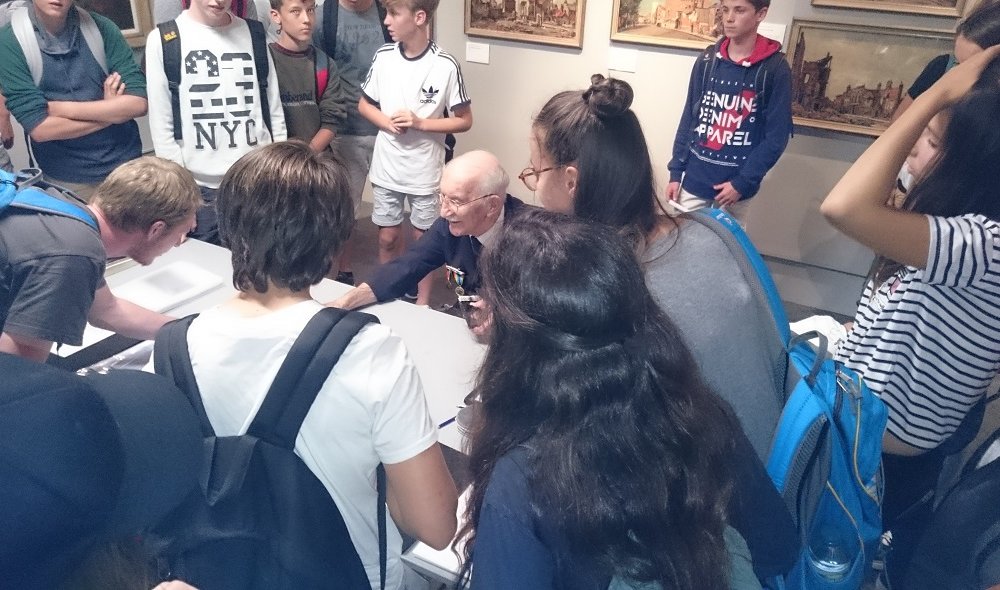

Some institutions are impossible to imagine without the presence of certain individuals. At the 2019 Museums + Heritage Awards, the story of one volunteer’s story stole the show for this very reason. The Volunteer of the Year prize was awarded to World War Two veteran John Jenkins, who has been working with Portsmouth’s D-Day Story museum since 2005.

“John comes to the museum twice a week to talk to visitors about his experiences,” Felicity Wood, public participation officer at Portsmouth Museums, explained. “His friendly, winning manner and wry sense of humour has won him friends from all walks of life. Visitors are overjoyed and often humbled to meet with someone who fought during the Second World War, but John effortlessly puts them at ease.”

Visitor feedback certainly endorses Wood’s praise. A Facebook post from a Norwegian visitor last year, for instance, said: “Best thing was that I got to sit down with Sergeant Major John Jenkins who went ashore on D-Day. A 99-year-old who could tell his experiences. That talk was worth the whole visit!”

The then 99-year-old has now celebrated his centenary, capping off a year which saw him receive praise from the Queen and U.S. President at commemorations for the 75th anniversary of D-Day.

In addition to his volunteering at The D-Day Story, Jenkins serves as a boardroom steward at Portsmouth Football Club. At the club’s home ground he carried the 2012 Olympic Torch and, in 2015, he became the oldest person ever to abseil down the city’s famous 170 metre Spinnaker Tower.

Placing Trust in volunteers’ hands

The National Trust had a remarkable 2018/19. Having spent £148 million on conservation and restoration – equivalent to more than £405,000 per day – its membership numbers leapt up by around 400,000 to 5.6 million.

While the Trust employs vast numbers of people, it also relies heavily on its legion of committed volunteers. One large-scale project led by these volunteers took place this summer, with Dorset’s iconic Cerne Giant being given a new lease of life by an army of unpaid workers armed with spades, pickaxes, brushes and 17 tonnes of chalk. The landmark is perpetually discoloured by the weather and growth of weeds, meaning a refresh is required approximately once a decade.

“We have somewhere between 60,000 and 70,000 volunteers. They’re amazing people who underpin everything we’re doing. Although models of volunteering are changing, volunteers are only going to become more important to us. We will use volunteers in more and more ways in future,” John Orna-Ornstein, National Trust’s director of culture and engagement, explained.

“We’re a membership organisation and all our members are part of a community that really care about National Trust places. What this means in practice is that quite a lot of them are happy to put in their time and effort to support us.

“The world is incredibly varied, as is the National Trust. There’s always something people can do with us, whether they want to donate one hour a month or give five days a week as some amazing people do.”

The work conducted on the Cerne Giant task was no small undertaking. As Natalie Holt, a countryside manager for the National Trust, explained after the 2019 update to the Giant’s outline was completed: “If you were working on the feet you’d have to walk 60 metres up the hill every time you needed to collect a new bag of chalk.”

329 volunteers worked for more than 1,181 hours on the Giant’s 460 metre outline. In terms of paid hours, that saved the Trust at least £10,629 (assuming all workers were being paid the current Living Wage).

I think we can all agree that this is a fine headline https://t.co/WLbsWomvnj

— Stephen Fry (@stephenfry) August 29, 2019

The project quite rightly received national attention. Stephen Fry’s Tweet and the subsequent tongue-in-cheek response from the National Trust perfectly distil the positivity that surrounds a group of committed volunteers working towards a cause they all care about. There are, however, potential pitfalls with the sector’s reliance on unpaid working hours.

Is it exploitative not to pay people for their time, and does the fact cultural organisations are accustomed to free labour encourage them to offer salaries below what would be deemed appropriate for permanent employment?

To address this, Louise McAward-White spoke with Advisor on behalf of Fair Museum Jobs. The organisation campaigns on fair and transparent recruitment, along with the ethical issues surrounding pay and jobs in museums and heritage institutions.

“On one hand,” she notes, “the message is that we want the sector to be more diverse and to encourage different people into the sector at entry level, but we also want people to have a certain amount of experience before they’re considered for an entry level job.

“This implies you will have had to work for free to gain the experience. A much less diverse group of people, or people who are having to make massive personal sacrifices, will be the only ones able to do this. Lots of people take non-museum jobs to enable them to volunteer. Not everyone has the luxury to be able to do that.”

Really dissapointing too see another ‘competitive’ salary, this time from @AmgueddfaCymru @Museum_Cardiff.

We cannot overstate how damaging the practice of salary cloaking is for the diversity, inclusivity and wellbeing of the sector. Please publish a salary range ASAP. pic.twitter.com/iGpQv0B7yE

— Fair Museum Jobs (@fair_jobs) October 28, 2019

Many people working in the sector will be familiar with Fair Museum Jobs’ Twitter campaigns, aimed at challenging job advertisements that don’t meet its standards on transparency or fairness. Roles badged up as apprenticeships, internships and volunteering opportunities are being used “a bit interchangeably” in the sector, according to McAward-White. Part of a trend which the group are looking to arrest.

While making clear there is “nothing inherently wrong with volunteering”, the fear among organisations such as Fair Museum Jobs is that the common practice of expecting people to work without pay can “devalue what work is and have a devaluing effect on wages in the sector”.

She encourages those advertising for unpaid roles to give applicants clarification on what will be expected. “Clearly state that it’s a volunteer role, don’t act like it’s a paid job. You must mediate your expectations. Asking for a postgraduate qualified person to work for nothing is devaluing the qualification of the sector,” she notes.

The main exception to the rule, acknowledged by the Fair Museum Jobs spokesperson, is the role played by trustees. These are volunteers that may well have to meet certain legal qualifications and have a base level of technical knowledge.

McAward-White concludes that there shouldn’t, however, be an assumption that just because many industry figures had to volunteer when they started in the sector that this should necessarily always be the case today.

To help people navigate the choppy waters of unpaid work in the sector Fair Museum Jobs has published dedicated volunteering resources which complement its Manifesto. It also points people towards advice and support offered by Creative and Cultural Skills Council.

Do you know an individual or organisation that deserves recognition like John Jenkins from The D-Day Story? Nominations for the Museums + Heritage Awards 2020 are open until 31st January! Find out more about the Volunteer(s) of the year Award here.