Collections management underpins the work of all disciplines of curation. Simply put, it is caring for the collections we look after to ensure their safety for future generations to use and enjoy. The work involved in collections management is everything we do on a day to day basis. This may sound bizarre, but it’s true. It includes storage, documentation, research, loans, security, safe handling, engagement, and conservation of collections – all the work we do to care for our collections to guarantee they are there for the future.

Natural history is an enormous subject which includes zoology (the dead animals from beetles to birds), botany (the pressed plants) and geology (the heavy rocks and the old fossils). With such a massive range of areas there are a diverse range of collection types; pinned insects, stuffed birds, fragile flattened flowers, spirit preserved creatures, wobbly skeletons, hazardous and toxic minerals, terribly sensitive sub-fossil bones and the tiny world set upon microscope slides to name just a few.

A natural history curator in the smaller local authority or independent museums will have to look after all of these different collections types. This can appear daunting; how do we manage spirit collections, and is this the same as managing sub-fossil bone collections?

The general principles of collections management for any type of collection is the same, and an understanding of this ensures that no matter what you are looking after, it will be looked after to the best possible standard. For example, the documentation will be the same no matter what is sitting in front of you; all the association information should be on the museum database, along with images and any new research/information that is discovered should be updated.

The difficulty can be when it comes to the more ‘specialist’ work, such as conservation of specimens, or storing specimens in the correct conditions so they don’t deteriorate or become a snack for pests. We may have experience with one type of collection, say pinned insects, but none whatsoever in another type, say spirit preserved creatures. Shall we focus on just looking after the pinned insects and putting the spirit specimens to the side?

Of course not! No one is an expert in everything. Good collections management is being aware of your own limitations and to seek advice if needed. A staff member in a museum thinking they know more than they actually do know is dangerous and will inevitably cause irreversible damage to specimens. It takes time and experience to understand how to manage different types of collections. This is learnt by talking to colleagues, not being afraid to ask for help and using the help and support of the subject specialist community.

The detailed care, conservation and storage requirements for the many different types of collections is beyond the scope of this short article (and could very easily fill a few books!). One useful book, in fact is available free online; Care and Conservation of Natural History Collections (1999) by Carter and Walker (http://www.natsca.org/care-and-conservation). This has some useful information and advice about looking after different natural history collections.

Below gives a very brief summary for the care of natural history collections.

Zoological Collections

This is a large and diverse collection including skeletons, taxidermy, pinned insects, shells, birds eggs, study skins, microscope slides and spirit specimens. Ultraviolet light will cause pigment in the specimens to fade. Damp environments can attract pests and encourage mould growth. Skeletal material can crack in too dry an environment and teeth in particular can begin to flake. If storing collections together the ideal temperature should be between 10oC and 22oC and the relative humidity (RH) between 45% and 55%.

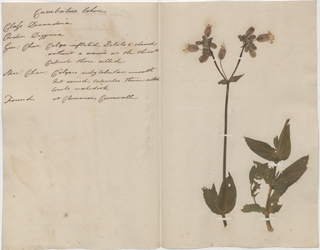

Botanical Collections

All the botany specimens are stored here. They include pressed specimens (called herbaria), dried specimens (lichen and fungi), spirit specimens and microscope slides. The dried and pressed botany specimens do invite pests to nibble away at the dried old buds and leaves. Pests can be limited by controlled environments in the store rooms; the temperature should be between 18oC and 22oC and the RH between 45% and 55%.

Geological Collections

These include petrology (rocks), mineralogy, palaeontology (fossils), plaster casts, models and microscope slides. Although rocks are pretty robust things, associated labels are not; these can become lost, or even eaten by pests. A familiar phrase ‘pyrite decay’ sends shivers down many a curator’s spine. This is when water in the air (a high RH) reacts over a long period of time with the mineral pyrite, causing it to crumble and decay to a pile of dust. It can be controlled, by specific conditions; with the RH below 45%. Ideally collections should be stored in collection specific storerooms, but this is not always possible. For a store room holding a number of different geology collections, the best conditions would have the temperature be maintained between 16oC and 18oC and the relative humidity between 45% and 60%.

Natural Hazards

Natural history collections hold a plethora of poisons, fumes, and natural toxins that if not managed correctly has the potential to cause serious harm;

• Zoological collections can hold arsenic soaps and powders, naphthalene, formaldehyde, industrial methylated spirit, and some old chemicals for fluid preservation.

• Botanical collections may have been treated with toxic chemicals and some can be stored in old spirits.

• Geological collections can hold radioactive minerals and rocks, asbestiform minerals, and toxic specimens (arsenic, antimony and mercury for example).

Although this short list sounds terrifying, an understanding of the hazards allows them to be managed correctly and safely. NatSCA and the GCG have both published related articles on how best to safely handle and store hazardous collections. (All back issues from both groups are available online; NatSca: http://www.natsca.org/publications and GCG: http://www.geocurator.org/arch/arch.htm)

If you have natural history specimens, and are unsure how to tackle a certain problem seek advice. There are subject specialist groups who can help and provide advice. The Natural Science Collections Association (NatSCA) and The Geological Curators Group (GCG) have regular training seminars, annual conferences and a large network of curators in different fields. These groups have a really useful JISC mail, where you can email queries and the email goes to all the curators who have signed up (and there are a lot!).

Back to top