London’s Natural History Museum has joined many other cultural sites in declaring a planetary emergency. Unlike its peers, however, the Museum is in a position where much of its collection is pivotal to ongoing scientific research which could mitigate the current climatic turbulence being experienced around the world.

Alongside a string of measures to lessen its environmental impact, the Museum’s strategy to help fight the climate crisis revolves around safeguarding and digitising its collection in a new purpose-built facility.

A new science and digitisation centre will help accelerate the digitisation of the Museum’s collection, facilitating institutions from around the globe to digitally unite more than 1.5 billion items online. At present only around 5% of the Natural History Museum collection is digitised. Despite this, 18 billion specimen and research records have already been downloaded from its internet resources to date.

Research to address issues including climate change, biodiversity loss, the spread of disease, feeding Earth’s growing population and the use of critical raw materials will all be boosted by the centre’s arrival, the Museum hopes.

Driving technological advancements forward will also be a key goal of the facility. AI, Big Data, genomics, remote-sensing and planetary exploration have all been cited as areas of interest when the new centre opens its doors.

Q&A with Tim Littlewood, executive director of science at the Natural History Museum

What have been some of the biggest challenges in storing and preserving artefacts in an antiquated facility?

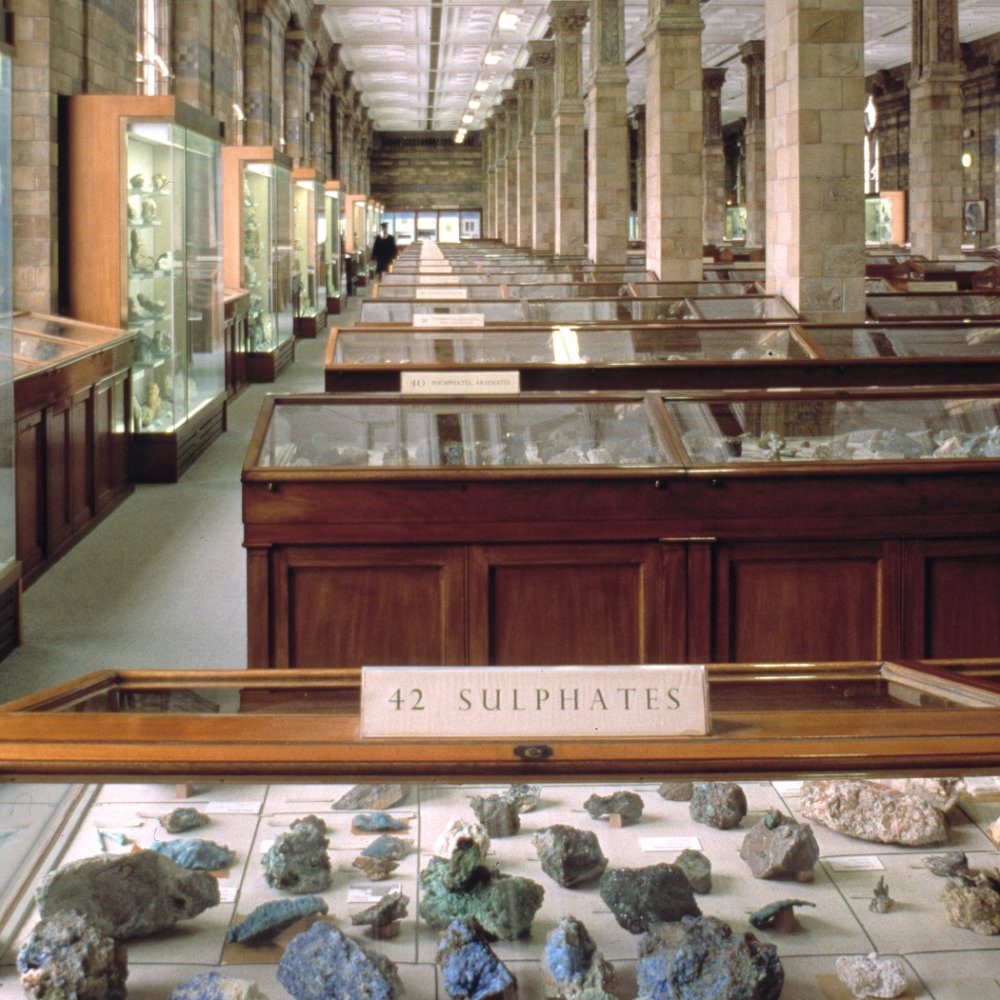

Many important Museum collections are stored in sub-standard conditions, putting important specimens at critical risk. For example, some of the current buildings have poor climate control and are at risk of flooding. Curators are undertaking “sticking-plaster” remedial conservation to keep collections safe, but have limited options while collections remain in current conditions.

We are actively seeking a new, modern facility to replace the storage in post-war buildings which are not fit for purpose, including our South London store. South Kensington will continue to be the home for the largest proportion of our collection and a strong centre of research.

What will set the centre apart from other stores and conservation facilities?

The new facility will improve physical and digital access to collections, laboratories, research technologies and data, accelerating the impact of research. The development will enable the Museum to secure and digitise its growing collections for the next century to provide a springboard for employing and developing new technologies.

How will the new centre change the way the Museum functions, and what new opportunities will it offer?

Doing this will give the Natural History Museum in South Kensington the potential to improve its offers to visitors. Releasing space at South Kensington by removing collections that are not currently on public display will also allow us to reopen historic galleries. Ultimately, this will enable more people to visit South Kensington and to have a more meaningful experience, with less overcrowding.

The new facility will provide a range of new employment opportunities, global collaborations and engagement with the local community.

Will there be any opportunity for the public to engage with the centre or will it be limited to museum professionals and researchers?

The museum is examining opportunities to involve local communities with the centre – for example, under active consideration is how we could use our experience as a STEM engagement pioneer to involve local school children in the work of the centre.

How vital does the Natural History Museum regard digitising all its artefacts?

It’s absolutely vital. At present this information is contained within hundreds of millions of specimens, labels and archives across the globe, yet only available to a handful of scientists.

Digitising the Museum’s collection is giving the global scientific community access to unrivalled historical, geographic and taxonomic specimen data gathered in the last 250 years. For example, an estimated 70,000 plant species are still undiscovered to science – but more than half already exist in natural history collections somewhere in the world.

Linking the collection with complementary data sets including DNA barcodes, will allow us to tackle global threats to our society, economy and environment. As scientific techniques improve, the power of big data in our collection will equip us to face unknowable challenges in the future.

As such, we want to unlock this treasure trove so that everyone, including citizen scientists, researchers and data analysts, can access it. Our new science and digitsation centre will enable this to happen faster.

Details of the centre’s exact design and the timeline for its delivery are yet to be confirmed.