I believe that the British race is the greatest of the governing races that the world has ever seen … it’s not enough to occupy great spaces of the world’s surface unless you can make the best of them. It is the duty of a landlord to develop his estate

The above quote from Joseph Chamberlain was made while he was Secretary of State for the Colonies (1895-1903) and features on the walls of a new exhibition at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG): The Past is Now – Birmingham and the British Empire.

It’s an uncomfortable truth that Chamberlain, a revered figure in Birmingham – Mayor from 1873 to 1876 and elected Liberal MP for Birmingham in 1876 – famed for his social policies should also be someone who supported what today would be tantamount to white supremacy.

Birmingham Museums Trust has just launched a £40m funding campaign to redevelop the Victorian museum and its galleries and the experimental Story Lab is part of the museum’s efforts to gauge visitor’s opinions on future interpretation.

The Story Lab is positioned in a small gallery within the museum and The Past is Now is the first exhibition to be featured with more to follow over the next two years. The traditional story of Birmingham’s relationship to the Empire would largely focus on it being a manufacturing centre, but The Past is Now expands on this by describing how guns made in Birmingham would be exchanged for enslaved people on the West Coast of Africa who were transported to the Americas.

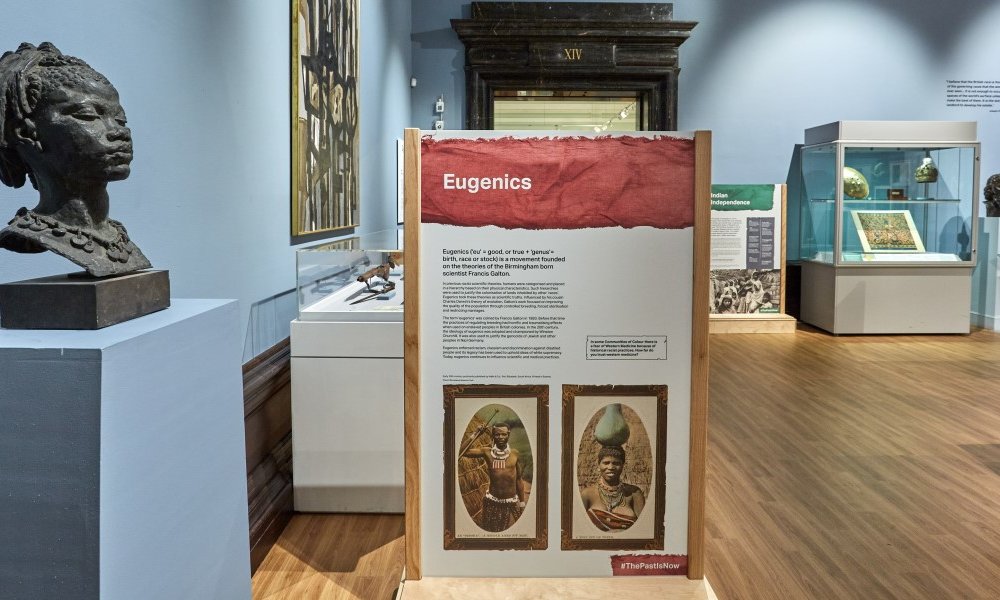

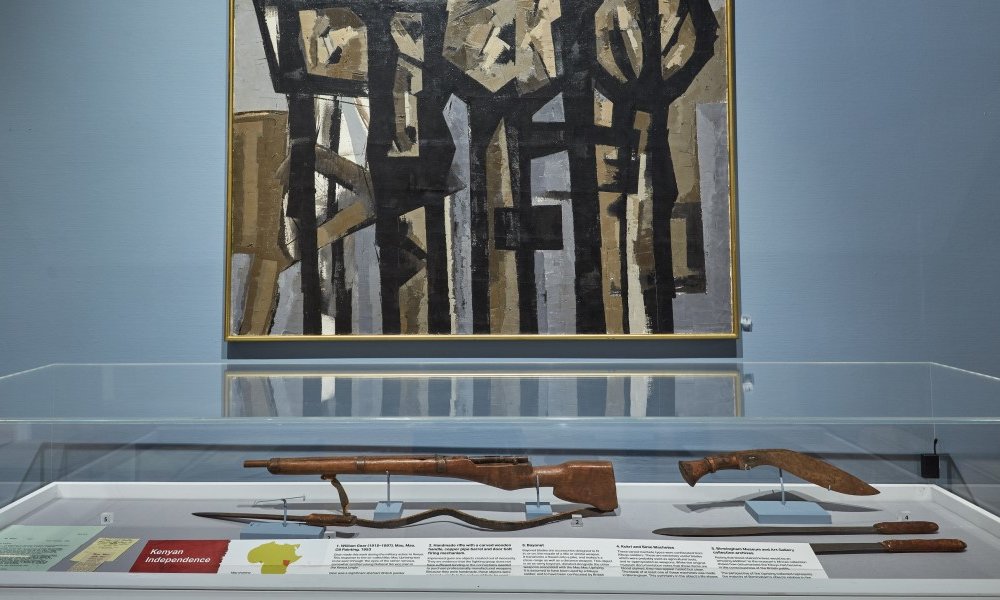

As the visitor enters the exhibition one of the first things they will learn is that the term eugenics was coined in 1883 by a Birmingham man, Francis Galton (Founder of the Eugenics Education Society) – another uncomfortable truth – and in another display the Mau Mau Rebellion (1952-1960), in what was British Kenya, is presented with exhibits that were donated by a former British soldier. What is jarring about this display of a blood-stained knife and a homemade rifle, is that in a letter from a curator, dated 1964, asking a colleague to pick up the objects, it says: “I thought they might make an amusing addition of a specialist sort to our African collections.” Which seems to pour scorn on the Mau Mau’s for making improvised weapons to defend themselves against an imperial force.

For this exhibition, Sara Wajid, who is head of interpretation at BMAG as part of a Arts Council funded Change Makers placement – a scheme that aims to address the fact that there is an underrepresentation of black ethnic and Asian minority ethnic and disabled people in senior management and leadership roles in the sector – has collaborated with six local artists and activists.

“I have been working in museums for ten years now and I can’t think outside my own brain so even though I think I might be relatively radical or have a diverse perspective, I’m still a museum worker and I’ve still got ingrained, trained ways of looking at collections and thinking about what is appropriate to tell in the museum,” says Wajid, who has Pakistani heritage, is also a senior manager at Royal Museums Greenwich and an active campaigner for diversity within museums. “And it’s only working with a new curator who has specialist skills in this area and with six cultural activists that we were able to stumble on the sort of stories that might surprise people, such as the version of the Joseph Chamberlain that we’re telling in this gallery, which is not one we would have explored without them.”

New Tone

The Story Lab, says Wajid, is being designed as a test lab to find a new tone and new themes that are going to resonate with audiences that haven’t been coming to the museum traditionally. Wajid started her placement in January and, not familiar with Birmingham, was surprised by its multicultural make-up.

“The project the museum wants to explore is different ways of telling stories of its Victorian collection and make it more relevant to a 21st century multicultural audience. As soon as I arrived in Birmingham and walked out of the train station I felt the city was at an exciting moment in its life, it felt very alive and I had not seen this particular mix of multiculturalism in quite this way. It’s different to London in a way that I hadn’t expected and I also knew there was a lot of activism going on in Birmingham around Black Lives Matter and around cultural representation.”

Wajid says the exhibition is timely as a term that has been used a recently in academic circles and increasingly in museum circles is ‘decolonise’ which refers to a way of opening up literature (as in the campaign by Cambridge University students to have a wider non-white reading list) and also collections to wider interpretation and ideas.

“What a lot of people are increasingly thinking about is how to decolonise our cultural institutions and at museums like this one, that are largely a product of the colonial imperial search for knowledge and categorisation of other cultures, we should be able to tell quite complex and diverse stories that do represent multicultural Britain. There is something in the very fabric of the way museum collections exist that are tied up with colonial mentality.”

The Story Lab is focused on getting as much feedback on this exhibition and subsequent ones through engagement in the gallery. Curators and volunteers are talking to visitors and giving them the opportunity to write down their thoughts on paper and a whiteboard at the entrance.

New Generation of Curators

“Within the museum I think we are seeing a new generation of curators coming through who are not only collections curators and subject specialists but are also being trained and equipping themselves in community engagement work. It’s making those links between audience and knowledge production and this is what Story Lab will do basically and this is the first attempt, of many, I hope, that combine these challenges to the museum in the production of an exhibition and opens up the processes of the museum.”

Wajid says the current exhibition is simply better than it would be if the museum had gone it alone. She says it’s more engaging and has more creative energy, freshness and knowledge as the amount of expertise has expanded. “So it makes a better quality production, better quality interpretation and it benefits museum audiences.” She says it has led to challenging conversations about cultural politics, authority, knowledge and power within the museum, which still makes it slightly inward looking. But for the future exhibitions the museum will try different modes, which are much more about wide-ranging consultation, which will involve ‘getting outside of the museum walls’.

Some members of staff on seeing the exhibition being completed cried because they found it so moving and impactful. One said it was the type of thing they had been talking about to friends for years but never expected to see it on the walls of a museum they worked in.

Wajid says that is the kind of emotional impact museum professionals are striving for in their institutions as they need to be relevant or otherwise face being obsolete.

The Past is Now – Birmingham and the British Empire runs until 12 March 2018.