In popular culture, crime scene investigations (CSI) have always piqued the public’s interest from Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional character Sherlock Holmes to the recent flurry of CSI TV series and back again to Benedict Cumberbatch’s portrayal of the Baker Street Sleuth in Sherlock.

However, there has probably never been a show quite as comprehensive in its detail as the Wellcome Collection’s Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime, which travels from crime scene to courtroom, across centuries and continents, exploring the specialisms of those involved in the delicate processes of collecting, analysing and presenting medical evidence.

The exhibition contains original evidence, archival material, photographic documentation, film footage, forensic instruments and specimens, and is rich with artworks offering both unsettling and intimate responses to traumatic events.

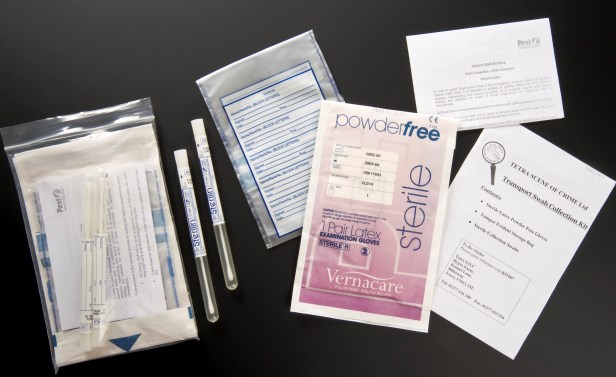

Two DNA swab collection kits used to collect spit. Issued by First Glasgow to bus drivers to tackle staff assaults through DNA analysis. Made by Tetra Scene Of Crime Ltd. Circa 2006. © Science Museum

“This exhibition gives alternative views of the forensic process from the CSI detections of popular fiction and television, whilst exploring the cultural fascination that the disciplines of forensic medicine inspire,” said curator Lucy Shanahan.

“Our journey from crime scene to courtroom takes in pioneers of scientific techniques that have revolutionised the way in which crimes are investigated, and offers visitors unexpected encounters with the changing relationship between medicine, law and society.”

Challenging familiar views of forensic medicine shaped by fictions inspired by the sensational reporting of late Victorian murder cases and popular crime dramas, ‘Forensics’ highlights the complex entwining of law and medicine, and the scientific methods it calls upon and creates.

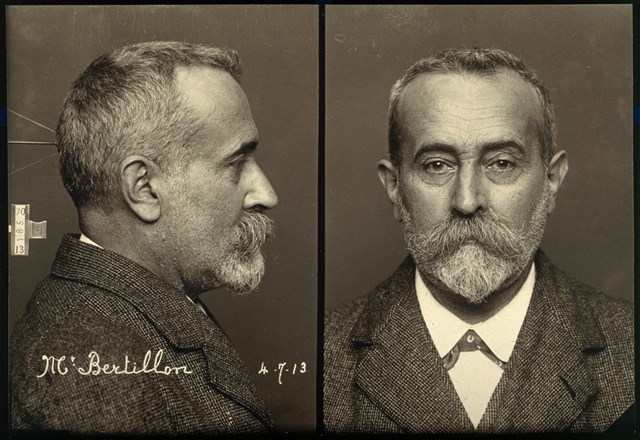

It surveys real cases involving forensic advances, including the Dr Crippen trial and the Ruxton murders, pioneers of forensic investigation from Alphonse Bertillon, Mathieu Orfila and Edmond Locard to Alec Jeffreys, and the voices of experts working in the field today.

The first of five sections in the exhibition, ‘The Crime Scene’, investigates the different techniques of recording the location of a crime and its power both as a repository of evidence to be examined and a haunting site of memory.

Representations of crimes and death scenes include sketches from the site of a murder attributed to Jack the Ripper, the work of Alphonse Bertillon, whose ‘God’s eye view’ brought methodological rigour to the new possibilities offered by photography, and Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell studies: intricate dioramas of domestic crime scenes built in the 1950s and still in use as training devices.

God’s eye view – ‘Affaire de Colombes’ Alphonse Bertillon photograph of a crime scene. Early 19th century. Credit: Le musée de la préfecture de police

‘The Morgue’ traces a history of pathology, from Song Ci’s 13th century Chinese text ‘The Washing Away of Wrongs’, often seen as the first guide to forensics, to the celebrity pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury, a selection of whose autopsy note cards are displayed for the first time.

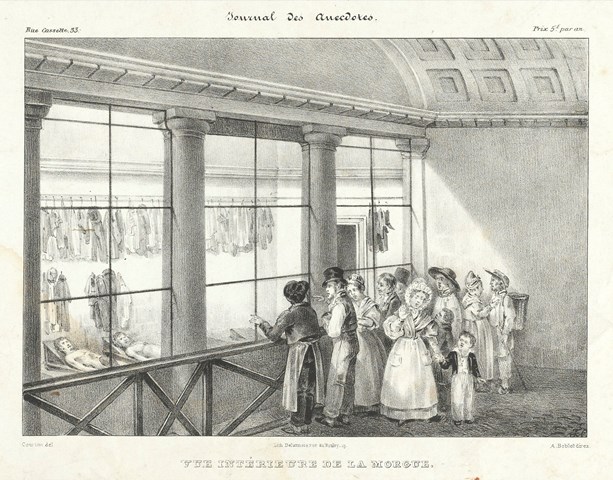

From a space for viewing corpses in Paris (the word morgue comes from morguer, ‘to peer’) to the virtual autopsies afforded by MRI, CT and 3D scanning, the morgue offers a vital space for questioning the dead.

A crowd gathers to view the grisly sight of the bodies, including a mother and her young son. Journal des Anecdotes 1820s

Edmond Locard founded the first police crime laboratory in early 20th century Lyon and his simple theory that ‘every contact leaves a trace’ (now known as the exchange principle) guides the array of disciplines, including serology, toxicology, microscopy, criminal profiling and DNA analysis that feature in ‘The Laboratory’.

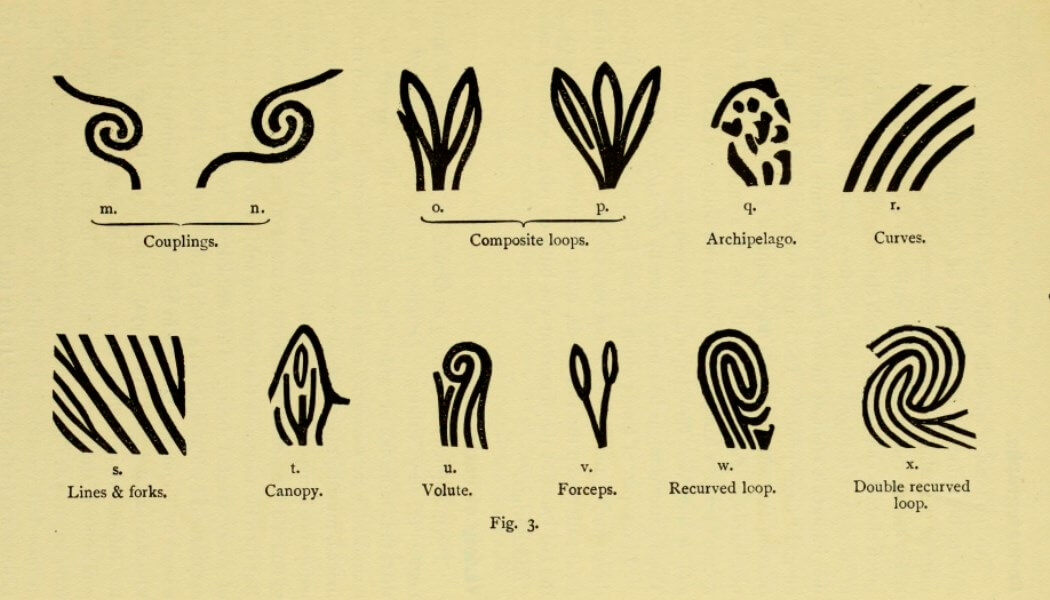

A succession of identifying and classifying techniques from Bertillon’s mug shots and physiognomic charts, Edward Henry’s fingerprint classification and Alec Jeffreys’ first genetic fingerprint, sit alongside the trace evidence techniques of blood and poison analysis that made traceless crimes visible.

Mug shots by Alphonse Bertillon. Photograph, 1913

Reconstructions of movement and identity required in looking for missing people are considered in ‘The Search’, both through individual cases and mass disappearances.

A newly commissioned artwork for the exhibition by Šejla Kamerić seeks to recover human stories behind the critical mass of statistics and data generated by the on-going identification of massacre victims in the 1992 -95 Bosnian war.

The work of forensic anthropologists and archaeologists is reflected through troubling artworks exploring facial reconstruction, by Christine Borland, sexual violence, by Jenny Holzer and, in the portraits and film of Alfredo Jaar and Patricio Guzmán, genocide in Rwanda and political disappearances in Chile.

‘The Courtroom’ marks the final test of forensic medicine’s success as evidence is gathered and presented in pursuit of justice. Forensic investigation has transformed the courtroom, but expert witnesses are subject to the less certain territory of performance when presenting their findings – a dramatic tension exploited both by charismatic pathologists like Spilsbury and Hollywood scriptwriters.

From the Roman forum to the Old Bailey the exhibition closes with the space which brings together the many strands of forensic medicine, either as a conclusion to an investigation, or to contest previous convictions.

Forensics: the anatomy of crime is free and runs from 26 February to 21 June.

Back to top