What are the main aims and objectives of the exhibition and why was the subject of dissent chosen?

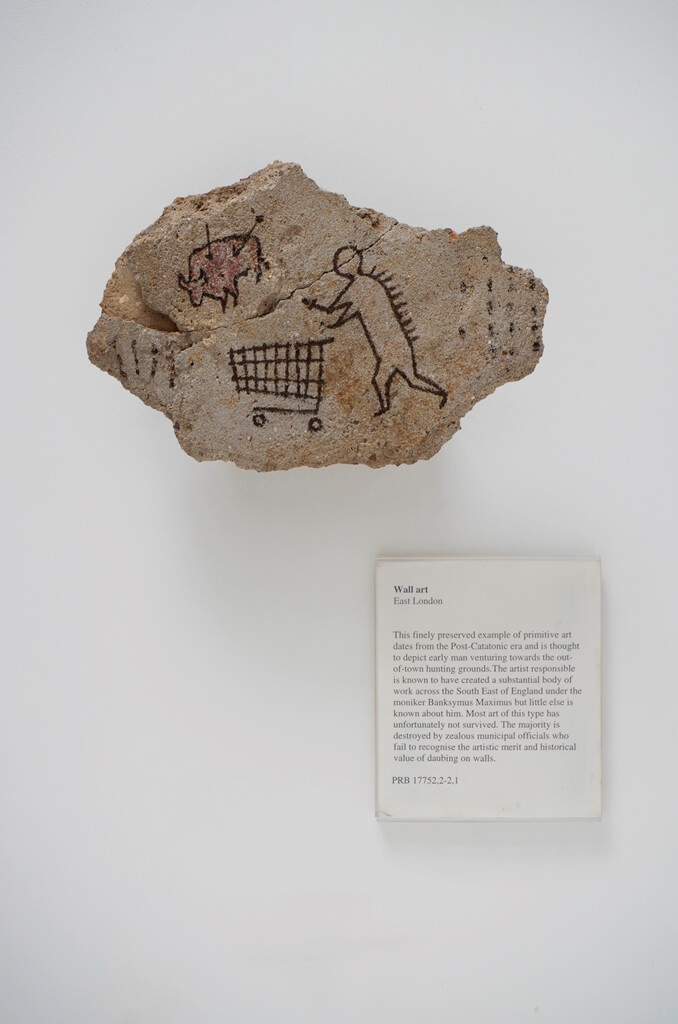

The intention was to uncover acts of creative disobedience by people, as told through the objects they have created, adapted, adopted and defaced. The objects are drawn from the British Museum’s collections, with two loans. It is an exploration of what one institutional collection can tell us about the human capacity to resist, mock, cajole, question and rebel against authority. It includes works by the downtrodden, the disenfranchised, as well as things created by and for powerful movements for change

Why was it decided to bring Ian Hislop in to help curate the exhibition and what do you think his curious eye will add to the subject matter that perhaps museum curators may not have picked up on?

It was important to have an outsider’s perspective. As curators we spend our lives working with material culture, but it can mean we’re a little blinkered when it comes to the more spontaneous themes that this exhibition covers. Ian was the ideal choice to act as the voice of the ‘outsider’ – as a journalist and satirist, he has a keen eye for subversive detail and could ask the sort of subjective questions that often elude curators, such as ‘what’s really funny about this object’? Of course, not every object in the show has a punchline, and Ian’s other great skill is having a nose for a good story, knowing which ones are the strongest, most evocative and which will appeal to visitors.

How did you and Hislop go about choosing the objects and how did you work together to get the most out of the collection?

We have spent three-and-a-half years researching and planning the exhibition. For the first two we simply went into departments and their object stores, where we met the experts – curators and collections staff – the people who know the collections better than anyone. With their guidance we began to choose objects and identify themes. For example, we found clothing and jewellery to be a recurrent theme, worn to reflect political, religious and social beliefs. Overt examples of subversion were found in the Department of Prints and Drawings, which has approximately 12,000 18th century British satirical prints. It was a huge challenge to whittle these down to half a dozen of the funniest, most savagely cruel works we could agree on. With some of the more subtle material, where dissent is hidden as allegory, metaphor or even in the form of hidden text, Ian acted as a useful litmus test for how our audiences might react. If he failed to immediately appreciate the symbolism of an object, it meant that either we weren’t telling the story in the right way or, more likely, that it wasn’t a very good story to begin with.

What will visitors see and experience at I object: Ian Hislop’s search for dissent?

Visitors to the exhibition will certainly see a wide variety of objects, including posters, teapots, coins, tunics, doors, rugs and puppets. Dissent doesn’t have a defined aesthetic – these objects were created by people who used the skills at their disposal as ceramicists, engravers, sculptors, weavers and even brick makers. Some objects are ingenious, others are crudely made and blunt of message, but they all share a healthy disregard for power and a willingness to question the status quo.

How has the exhibition been designed to excite and inspire visitors – what processes/technologies have been used?

Through the layout and design we wanted to recognise that dissent is chaotic and doesn’t have a clearly defined beginning, middle or an end. It usually just evolves into something else. The exhibition is therefore more open and free-flowing than visitors might expect, and there are many openings in the case framework enabling them to see across the entire space. The exhibition also makes wide use of digital graphics and animations to help the visitor to understand and to ‘read’ the messages hidden in objects, showing them where to look and how to interpret the imagery they encounter. Finally, visitors can also listen to excerpts of subversive music via two audio posts, featuring tracks as diverse as a Peruvian dance, a piano opus, a Korean lullaby and Creedence Clearwater Revival. Like the objects in the exhibition, subversion in music crosses all genres.

What were the challenges in creating I object: Ian Hislop’s search for dissent and how were they overcome?

Inevitably, we ended up with far more material than we could ever include, and there were some painful moments as we reluctantly dropped objects from the list. This won’t have been the first exhibition to encounter this problem, and it certainly won’t be the last.

I object: Ian Hislop’s search for dissent runs until 20 January, 2019