The pressure to make collections available online isn’t new. Back in 2015, Museums and Heritage published a survey that saw more than half of the senior leaders interviewed from the sector citing engagement and sharing digital content as their key priority. The Covid-19 pandemic increased that demand as in-person visits became scarce. International venues like the British Museum saw nearly a total loss of visitors and corresponding revenue, as organisations worked tirelessly to create virtual exhibition experiences and boost engagement with collections.

Almost a decade on from the 2015 survey, cultural organisations continue to face the often overwhelming challenge of organising, preserving, and sharing their digital collections to encourage engagement, increase awareness, and help generate revenue. In this post, we’ll expand on some of the tools that help museums and galleries enhance their collections.

CMS and DAM: Different by Design

Two essential technology components lie at the heart of this: Digital Asset Management (DAM) systems and Collection Management Systems (CMS). CMS platforms specialise in cataloguing and documenting physical artefacts and collections. Used well, the CMS can assist with tracking an object’s provenance, managing exhibitions, and facilitating research. DAM systems, on the other hand, offer robust solutions for storing, organising and

distributing digital content. From images and documents to multimedia files, they provide comprehensive tools for example with metadata management, version control, and access permissions.

To get the most out of these core systems, it’s recommended that they’re integrated with one another. The advantages of integrating CMS and DAM are many and varied: time-saving, security, preservation, duplicate prevention, and generally taking advantage of the unique features that each platform has to offer. A DAM system, for example, will have specific tools that are useful for images and media, whereas a CMS will include features that are more relevant to the original object being digitised. Usually a CMS has the option to upload one or more reference images independently and apply it to each object record – but it’s good practice to hold all images in a DAM and use that as the image source for the CMS.

Zooming in on IIIF

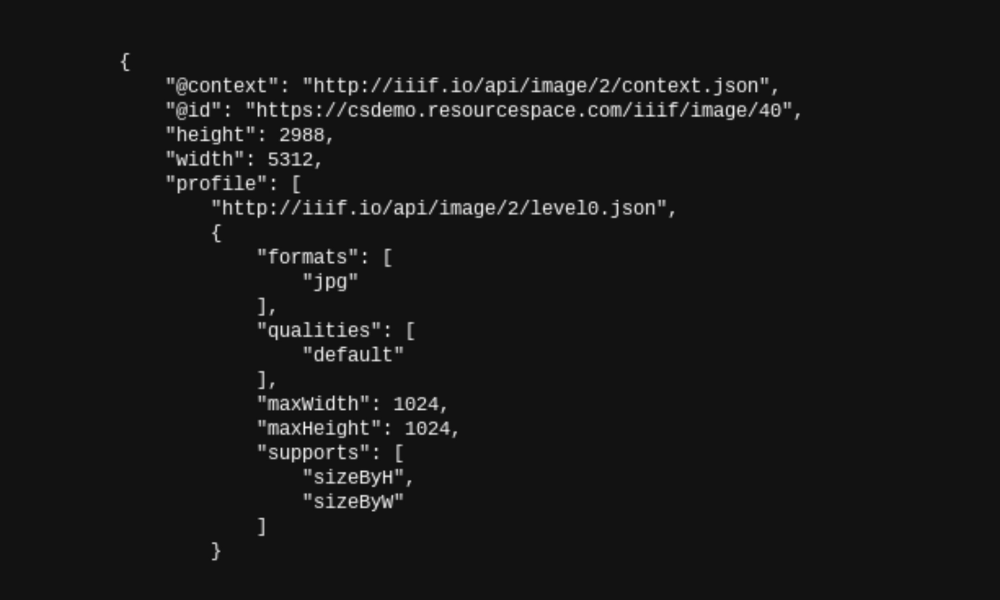

One such feature that works with the unique design of a DAM system is the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF). IIIF is a universal language for digital images and documents. It’s a set of rules and standards that allow museums and other cultural institutions to easily share their digital collections online in a way that’s accessible to all.

What is IIIF?

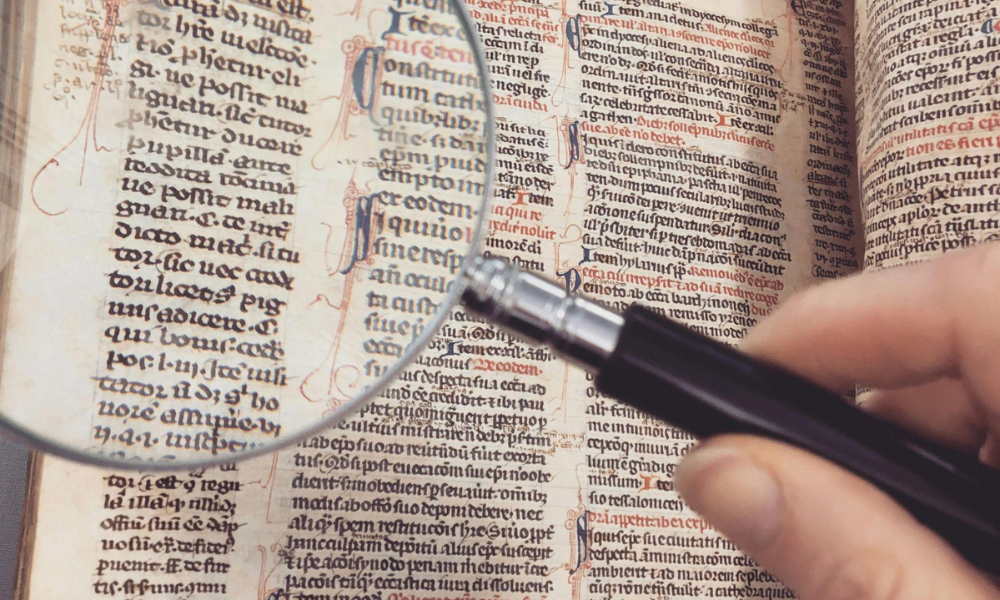

IIIF was developed by, and for, the education and cultural sector. Conceived as a community tool, IIIF technology benefits academics, curators, researchers and wider audiences as it gives enhanced digital access – objects can be seen in detail from any location. Having the opportunity to share content in this way can also strengthen the cooperation between organisations.

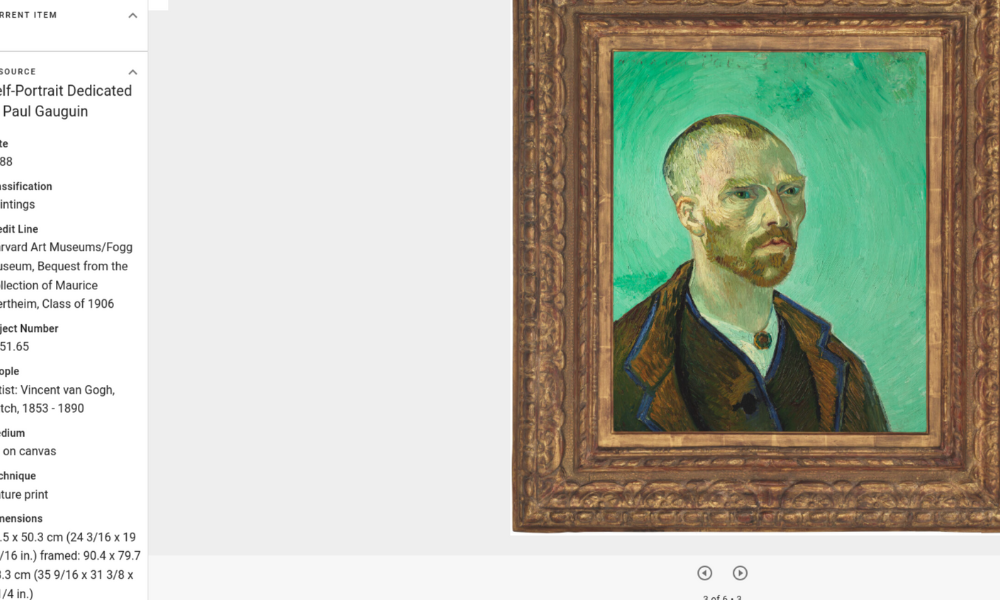

IIIF breaks down digital images into smaller pieces or ‘tiles’. These tiles are then served up to users on-demand, which means that viewers can zoom in, pan around, and explore an image in incredible detail, all without needing to download the entire file. The enhanced magnification means that users can zoom in, for example, on the minute brushstrokes of a painting, or microscopic text in ancient manuscripts.

Understanding the mechanics

IIIF is a tool for delivering digital assets rather than storing them: it provides a seamless exchange and presentation of digital items without the need to share large files. The tool works using ‘manifests’ – unique metadata templates containing basic information and sub-elements relating to a resource.

To do this, a URL links to a page overview of an object, which can be parsed into different formats such as information about thumbnails, licences, and sequences – information about the ordering of different views of the object, such as pages of a book, or various angles of a three dimensional artefact. These sequences contain canvases, which represent each page or view, and comprise of both thumbnails and details of the actual picture.

Because of its advanced zooming capabilities, IIIF is particularly useful for viewing art and artefacts such as paintings, drawings, maps and manuscripts. And because it doesn’t rely on storage it helps to bridge the gaps between disparate collections, enabling global collaboration between institutions.

Key applications of IIIF

Instead of just posting static images to a museum collection area, IIIF gives users the ability to interact with digital collections in meaningful ways. For example:

– Researchers can zoom in on specific details, whether analysing text close-up for translation or interpreting visual aspects like paint application methods and techniques

– Educators can create interactive lessons that give students a better understanding of the artifacts being discussed

– Wider audiences can explore collections from the comfort of their own home.

Virtual Tours and Augmented Reality Apps

Alongside the larger platforms that ‘drive’ the digital content we see in online collections or the printed information that sits next to the real works in a gallery, there’s a rapidly growing number of digital tools being developed to help engage visitors both in-person and online.

Virtual tour guide builders like STQRY and augmented and virtual reality studios like CURIO both specialise in digital interpretation for museum and heritage organisations.

Speaking about a CURIO augmented reality project with the National Gallery to recreate the San Pier Maggiore, a lost Florentine church, Caroline Campbell, Director of Collections and Research, said:

“It’s been really exciting for me and my colleagues … to work on creating an app which can take people from 21st century London to 14th century Florence and to put this painting back into the lost space for which it was made 700 years ago.”

Visitors and locals in Florence can even stand on the original site of the church (which was demolished in the 18th century to make way for a covered market) and use the app to generate the augmented reality church around them.

Enhancing, not replacing

As part of their wellbeing programme the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao devoted a section of the gallery to an experimental installation where visitors can log how specific works in the collection make them feel. As they look at the works in the Museum Collection, they can explore the emotions they trigger, and learn about other visitors’ feelings.

The ‘Artetik’ experiment has since been incorporated into Google Art & Culture to provide free access for anyone online to view and respond to the collection. Projects like this

enhance the experience of a collection by providing access to those who can’t visit in person and also complimenting, without pretending to replace, the real-life visitor experience.

What’s next for digital curation?

According to the Art Newspaper, visitor numbers are increasing again since the global shutdown, but are yet to return to the peaks they were reaching in 2019. Digital collections, and the tools that enhance them, will never replace the in-person experience of visiting an exhibition or collection. But in the case of cultural heritage, it’s universally understood that more is more. A strategic approach to digital curation that helps viewers engage with collections and exhibitions in enhanced and innovative ways can make all the difference, and fortunately there are an ever-growing number of tools that can help.