When you think of an archive, what springs to mind? It could be shelves reaching to the ceiling, piled high with boxes, or cans upon cans of film reels and stacks of tapes. It could just be a box of VHS tapes sat in your attic with ‘Spain 92’ or ‘Christmas 88’ written on the spine. It would be reasonable to associate an archive, and the contents within, with the past. Knowledge, memories and culture, once useful but now stored away and possibly even forgotten. As custodians of our own, we look at archives differently. Acutely aware of how formats – once at the cutting edge of standards – can be left behind through advances in technology, we understand that storage doesn’t mean preservation, and preservation doesn’t mean utilisation.

In a worst-case scenario, improper storage will lead to rapid degradation across all legacy formats, from film to analogue and digital tapes. Moisture can cause mould to form, reels can warp and shrink, and tape can be damaged to the point where there isn’t enough information to produce a usable transfer. Alternatively, while optimally-stored assets in pristine condition may not face degradation, they could instead face obsoletion. Even the most modern of tape formats are a relic of the past. The machines used to play them are largely only available as used, and what remains is only getting harder to maintain as they age. What use is proper storage if the content within is inaccessible? A modern archive should be digital and forward-facing; its contents accessible, commercially exploitable, and safe from technological advancement.

In this sense, one of the more future-proof legacy formats is film, with continuing advancements in transfer technology pushing towards 8K and higher, should the source be suitable. In this case the technology is there to serve the content, rather than leave it behind. But even when a format is perfectly preserved, and even when we have the means to get the best from it, there still has to be the will – commercially or culturally – to bring the content into the digital age and to a new audience.

When we were given the privilege of transferring over 600 assets from the National Army Museum’s archive, a huge motivation was the historical and cultural significance of the content within, and the role we would play in allowing the footage the chance to be seen by generations to come. The formats ranged from VHS and U-matic to 8, 16 and 35mm film, which gave us a variety of challenges to overcome. Each and every asset needs to be logged into our system and its condition carefully assessed before we can even think about putting it through the digitisation process.

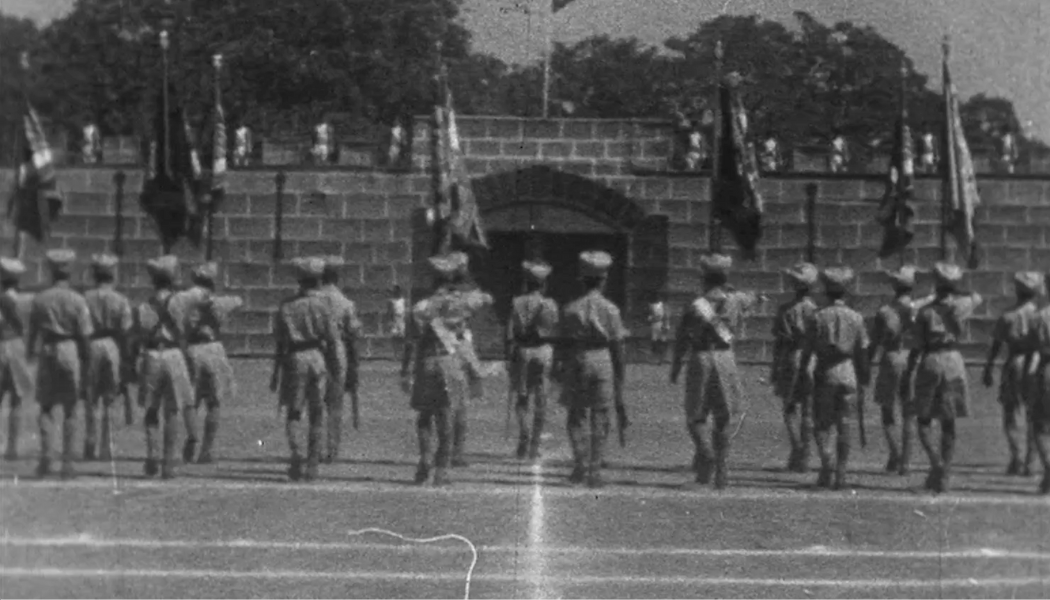

Thankfully they had been stored so well that – amongst the hundreds of tapes and film reels – only one was unable to be transferred. A reel of 8mm film that had dried and deteriorated so much it crumbled at the slightest touch, and seemed to have succumbed to rust. It must have had quite a journey before it landed with NAM. Sadly too late on this occasion, but there were hundreds more success stories during this exciting project. Reels of film showing Soldiers in the 1940’s relaxing on a hard earned day off, bathing in the sun and swimming by a dockside.

The majority of the assets were VHS tapes, with over 500 needing to be transferred. In order to transfer as quickly and efficiently as possible we had 3 VHS players working in tandem, digitising for 16 hours a day, transferring almost 300 hours of footage. That amount of work doesn’t come without its hiccups though. We were regularly pausing the process in order to clean the machines, swap out ones that needed a little TLC in order to keep running, and compare picture output from deck to deck (certain decks get a better picture from certain tapes, but you don’t know which until you compare).

Along with the vast amount of VHS tapes there were also some U-matic tapes, which are well known to be a tricky and temperamental format. Ceasing up over years of being stationary, they need a particular type of treatment – known as tape baking – to loosen them up and get them turning again. The process isn’t too technical. As the name suggests, it involves putting the tapes in a specially designed ‘oven’ and leaving them to bake. They are put on a heating cycle that takes 13 hours to complete, then left to settle for another 24 hours before attempting to play them. A long process but certainly worth it to get the best result and make sure the content isn’t lost.

As well as the tapes, we received over 100 film reels to scan, most of which were 16mm. Once the assets have been properly logged and assessed, it’s time for them to be cleaned. A speck of dust on the surface of the film may be invisible to the naked eye, but when scanned at a viewable resolution, that piece of dust is going to be a very visible blemish. We run every reel we ingest through our film winder, on which particle transfer rollers gently pull off surface dust and dirt. It’s a non-destructive and chemical-free way of preparing the film to get the best possible transfer. When it comes to the transfer itself, our set-up is tailor made for mass-ingest of archive material. We can ingest to HD or UHD in real time, and can even ingest picture and sound simultaneously to speed up the process further. This was crucial in allowing us to meet NAM’s deadline requirements.

In their own words, ‘The National Army Museum has worked with a few companies in recent years to digitise different parts of the collection and make them more accessible to the public. We found ITV Content Delivery to be very competitively priced, easy to work with, friendly and efficient. The time frame we gave them was fairly tight but they were able to accommodate our needs without a problem. As a heritage organisation it’s important to us that our films are treated professionally and with great care, and this is what they provided. Working with the ITV Content Delivery team has allowed the Museum to open up our film collection properly for the first time, and we look forward to the possibility of working with them again in the future.’