Winston Churchill, Joseph Chamberlain and Princess Diana were some of the names associated with the Newman Brothers through death, with their coffins adorned with the handles and funeral furniture made by this entrepreneurial Birmingham firm.

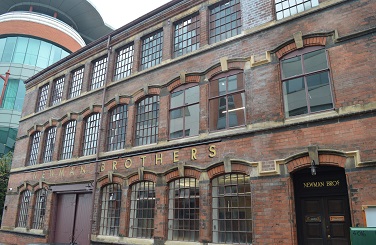

Back in 1892 brothers Alfred and Edwin Newman, brassmakers in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, decided to make the most of the Victorian’s obsession with death – epitomised by Queen Victoria who had been mourning the death of her husband Prince Albert since 1861 – and expedited by the diseases and poor sanitation of the time. They commissioned an architect and in 1894 moved into the three-story L-shaped building with its own stamp room, electroplating shop, shroud room, stables and courtyard.

It was during this period, between 1880 and 1914, that Birmingham and the Jewellery Quarter experienced a high point in its manufacturing output and by 1913 there were 70,000 working in the quarter compared to 6,000 today (it is still the largest maker of jewellery in the UK). The Newman Brothers’ decision proved fruitful – their reputation sealed when their fittings were used on British statesman and Birmingham MP Joseph Chamberlain’s coffin in 1914. Business continued until the end of the 20th century when the factory was included in an English Heritage (EH) survey on the Jewellery Quarter and its architecture in the late 1990s, which was internationally recognised and under threat.

Newman Brothers in 2001. Photograph by English Heritage

Following a 12-month restoration the factory has a fresh look – September 2014 – photographs by Adrian Murphy

“From then on there was a campaign to try and save it and Joyce Green [who joined to company in 1947 in the office and worked her way up, eventually becoming the owner] was very keen that the building be turned into a museum to see how the business was run,” says Simon Buteux, BCT director. “The EH survey gave the building Grade II star listed status, which meant it was significant because all the contents were intact.”

The Coffin Works was bought in 2004 from Miss Green by regional development agency Advantage West Midlands (AWM) with plans to restore it, however, the plans were dealt a blow when recession hit in 2008. “BCT was in partnership with AWM putting in expertise and grant applications. Then in 2010 the trust bought the factory for a good deal less with help from a grant from Birmingham City Council,” says Buteux. “It was Elizabeth Perkins, former director of BCT, who oversaw the transformation of the successful Birmingham Back-to-Backs [another BCT project now run by National Trust], who was inspirational in all this. I have had the lucky job to take the project to the opening stage and came in at the time to appoint contractors and move the project forward.”

BCT put in its first Heritage Lottery Fund application after the purchase and in 2011 was awarded just under £1m. “Why it took from 2011 to 2013 to get started was that we had to get the match fund and we have a list as long as your arm,” says Buteux.

Restoration begins

When BCT had the match funding in August 2013, bringing the total to £2.3m, FWA Conservation Ltd, builder and decorator by appointment to the Queen and M+H Awards winner in 2013 for Conservation, was brought in as the main contractor. “The brief was to take a very dilapidated building built in 1894, which had hardly any maintenance work since the doors were closed in 1999 and to transform it into a heritage attraction and commercial rentable space,” says Chris Lamb Business Development manager for FWA Conservation Ltd. “Which meant the 1960s quadrant and the rooms to the rear of the Victorian building were to be rentable units and the front elevation and stamp room would be kept as a heritage attraction.”

The Quadrant with the Victorian building ahead and to the right and the 1960s extension to the left

“We had to approach the two spaces differently, for example, we were very considerate in conservation of the heritage space, careful to leave as much as possible of the original fabric of the building intact whilst ensuring the Coffin Works complied with current building regulations, the most challenging internal aspect was the fire compartmentisation. “The windows were one of the major and most time consuming restoration aspect of the entire project and key to maintain the integrity of the historic nature of the building. “Out of 98 windows only three had to be replaced and these were cast locally. The balance were painstakingly refurbished in situ. There was also a policy regarding the glass – one crack and it remains in and two cracks and it was out. We had to match the glass that was to be replaced. The bottom two panes of glass were either frosted or fluted to stop the Victorian workers being distracted by the coming and going on the street below.”

The restoration of the machinery in the stamp room was carried out by Ian Clark Restoration and the signage was undertaken by HSN Signs in Birmingham, who completed the main Newman Brothers’ sign at the front and signs painted freehand onto the original brickwork to the sides of the building.

New gates were fitted to the trade entrance

The experience

“The factory was like the Mary Celeste with equipment and stock left,” says Buteux. “However, by 2007 the state of the building got so bad that in order to protect it all the moveable contents were taken out and put into storage.

Artefacts left in situ included coffin decorations, handles and screws, many still in their boxes

“At the end of August the restoration was finished and we could begin moving in ready for the opening on Tuesday, October 28. “It was only in September that the artefacts began to be transferred back to their Fleet Street home – although a little bit was left to show people pre-restoration and the popular candle-lit tours. “The challenge now is to put all the pieces back. They were all catalogued and photographed in situ.”

This is being done under the watchful eye of collections and exhibitions manager Sarah Hayes who joined the project and BCT in January 2014.

“It is going to be an immersive experience into Birmingham’s industrial past with demonstrations and recorded interviews from former staff including a recording of a real undertaker placing an order,” says Buteux.

One of those original travelling salesman was Dai Davies and there will be a case study depicting his work in the 1960s.

Visitors will be able to step into the life of a travelling salesman and see what he would have carried in his bag

This will tie in with the factory’s main office being set in the 1960s with the date on the calendar showing the day Winston Churchill died (and bringing him in as a link to the factory’s fame).

One of the reasons for this 1960s theme is that much of the furniture that was left at the timing of the company’s closure was from that period, including filing cabinets, electric fire and typewriters – the company had never moved with the times and there was not a computer to be found in the building.

Another fascinating aspect of the Coffin Works is the lives of the ladies who worked in the shroud room, making burial sheets for the dead.

The Shroud Room with its original sewing machines will tell the story of the seamstresses

A shroud made at Newman Brothers

Through the audio interviews recorded in 2000 the visitor will be able to delve into their world and hear how the women would describe themselves as seamstresses, especially if they were courting, as they didn’t want to allude to the morbidity of their real trade, unless they wanted to get rid of unwanted attention. As well as this there will be a reconstruction of their tea station.

Nearby in what was the showroom overlooking the courtyard there will be a temporary gallery space with rolling exhibitions. The first of these will be Shadows of Dust by Andy Garbi, an Arts Council funded project with the sounds of the Coffin Works set along time-lapse photography. This will be followed by an exhibition by the Midlands Textile Forum modern take on funerary etiquette.

A new business plan for BCT

A big part of the Coffin Works’ business plan will be the commercial side, where tenants will pay to rent out units for professional purposes. There are seven in total and currently a jeweller and a yoga school are already in residence. BCT have also taken two units making the Coffin Works its new headquarters, where it will continue its conservation work in the city. “This is the first time we have owned a building, restored it and now want to run it ourselves,” says Buteux.

Birmingham Conservation Trust director Simon Buteux

“We have never been landlords before and have had to learn to draw up leases. We needed a new model for the trust – the model we had from 1978 was to buy derelict historic buildings, restore them and sell them on. We saved buildings on a rolling fund model. What went wrong with that was it now costs more to restore a building than it would be worth commercially. There was a recession deficit and you cannot sell for a loss. The difficult thing now is to be sustainable and make money.”

Financial sustainabilty

BCT realised that in order for the Coffin Works to be a success it needed to create revenue streams within the building. It will do this mainly by running the heritage attraction and charging for entrance and renting the units. As well as this BCT has a supporters group with annual subscription fees, and from October members will be entitled to free entry to the Coffin works.

There is also a meeting room in the Coffin Works, which has already been hired out by businesses that have broken their day up by having a tour of the factory. BCT hopes this will be a winning formula. Another plan is to convert a temporary storage space into a café for daytime visitors and those attending evening events. “We want it to be a venue and a hub of activity,” says Buteux. “There are ideas in the pipeline which involve arts and food-related events and we hope to show films on the back wall of the courtyard and son et lumiere shows. We want to bring audiences into the building that wouldn’t normally come into a heritage attraction.”

In order to meet its funding requirements for the first year BCT needs to welcome 15,000 visitors through its doors, but with its flexibility as a venue the trust is hoping for many more.

The Coffin Works will open on Tuesday, October 28.

Back to top