San Pier Maggiore was one of Florence’s oldest, finest and most important Renaissance churches. Demolished in the 18th century, today, it is a bustling site of shops, cafes and apartments.

Dedicated to the apostle, St Peter, the church went through several renovations from the early 14th century until knocked down in 1784, after it partially collapsed. Whilst largely forgotten, even by those who live and work within the area where it used to stand, the urban fabric of Florence still bears the imprint of the church’s sacred architecture.

Within the church stood the multi-tiered altarpiece by Jacopo di Cione; most of its painted panels are now in the National Gallery’s collection and can be viewed in Room 60.

As part of the National Gallery’s Research Centre Seminar series, the Gallery recently unveiled Hidden Florence 3D: San Pier Maggiore — a digital placemaking AR project that reunites the altarpiece panels with the church they were created to adorn. People are able to see the large polyptic in its ‘original location’, walk through the church itself and understand the relationship between Jacopo di Cione’s paintings and one of the most important religious institutions of Renaissance Florence.

Unveiling Hidden Florence

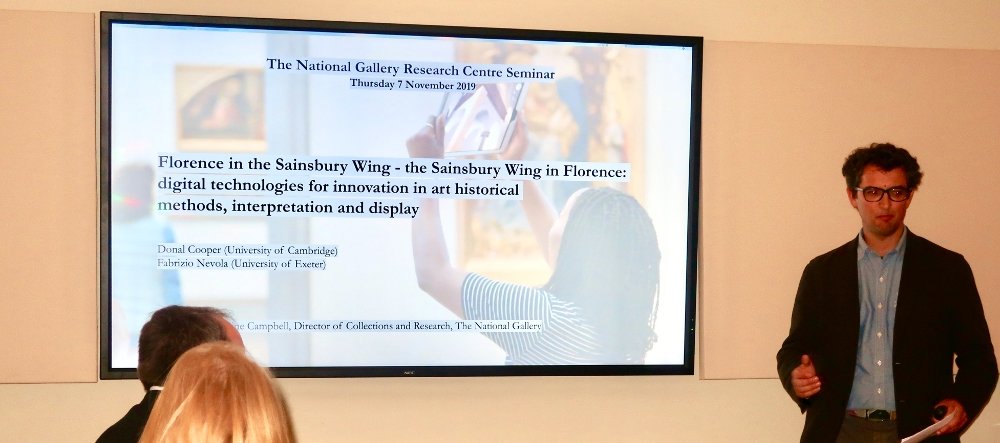

Hidden Florence 3D is a project built in collaboration between the National Gallery, Calvium, Professor Fabrizio Nevola of the University of Exeter, Dr. Donal Cooper of the University of Cambridge and Bristol-based studio Zubr.

On the evening of 7th November 2019, guests gathered in the National Gallery to experience Hidden Florence 3D for the very first time. The augmented reality app allows people to walk around the virtual interior of San Pier Maggiore on an audio-guided tour, witnessing the original altarpiece in its 14th century Florentine setting.

Professor Nevola, the National Gallery’s Director of Collections and Research Caroline Campbell and Dr. Donal Cooper welcomed everyone and invited them to experience San Pier Maggiore on their iPhones and iPads. For about 20 minutes, the guests revelled in the experience of exploring the church and seeing the altarpiece in the context for which it was created.

After the unveiling, our visitors walked through the Gallery to the Boardroom to hear a presentation from Donal Cooper and Fabrizio Nevola about the research process that went into forming the creation of the 3D model, as well as their extensive documenting process.

The Research Behind The App

Professor Nevola started the presentation by revealing some of the technologies used in Hidden Florence 3D — a combination of 3D modelling, GPS, and GIS (geographic information system mapping). Dr. Cooper then presented the research approach and methods undertaken to establish the form and fabric of the church.

“Here, we are building on the research of others – those who were involved in the 2015 exhibition of the church and its archives, as well as others at the National Gallery who worked on the reconstruction and study of the panels of the altarpiece, the American University who studied the fabric of the church, those researching the iconography of the altarpiece, and so on.”

– Dr. Donal Cooper

To recreate the entire church, the team had to rely on several sources, as the plan that was illustrated in a catalogue of the Botticini exhibition (one of the main representational records of San Pier Maggiore) was deemed an unreliable record. For instance, the reconstruction of the altarpiece in the 3D model was based upon the work of Professor Jill Dunkerton’s book called Italian Painting Before 1400: Art in the Making.

Meanwhile, other aspects of the building in the computer generated reconstruction were derived from sources including conventional site surveys, historic plans and old city views available in paintings, the latest photogrammetric techniques and early Trecento churches (e.g. San Remigio di Firenze church) also provided details and contextual information. Over a number of years, all of this information was expertly gathered, sifted through, analysed and stitched together in order to develop a coherent representation of the church.

“In 2019, we had to commit to a rendered model which is more challenging in many respects than a data cloud model,” Donal Cooper said.

For the design and build of the model a wealth of contextual information, such as images with reams of notations, was sent regularly to the teams at Calvium and Zubr. At this point, with much to and fro, the teams worked out how to use the data to provide visitors with a compelling experience as they walked around the demolished 14th century church rebuilt in the 21st century gallery space.

For Calvium, this challenge of establishing the best way to elicit academic knowledge and translate it into a form that the 3D modellers could interpret unambiguously was a fascinating aspect of the experience design process.

Next, Professor Nevola explained how the project team documented the decision-making process in the model and the sources that inform it. He said that working with San Pier Maggiore is difficult as it involves reconstructing a church that is no longer there. Echoing Donal Cooper he reiterated that there were several fragmentary and visual sources, which meant looking at comparable churches to fill in the blanks. The academics had to make decisions at every step of the project, which would then be visualised in software.

“In the model that we’ve put back into Room 60, those decisions were rendered solid,” he said.

This project raises the issue of certainty and uncertainty. In the world of art history and 3D modeling, how do you tell people when you aren’t 100% sure? How do you put the footnotes into these models and make them robust in a scholarly way?

To answer this, Professor Nevola showed us an ontological map to demonstrate how they “addressed it head on.” The map was a way of structuring information in a relatively schematic way that is quite rigid at the same time, so that a computer can read those decision-making processes.

Calvium’s Role in Hidden Florence

We initially worked with Professors Fabrizio Nevola and David Rosenthal of the University of Exeter back in 2014 for the first iteration of the Hidden Florence app, which allows users to go on a free guided tour of the city in all its Renaissance glory. After its success, we added more content to feature new stories and characters, including that of San Pier Maggiore.

The reimagination of the church into 3D AR was a real test of our project management skills as we collaborated closely with academics and commercial partners and all within a set budget. The technical aspects were also a massive challenge for many reasons, e.g. integrating AR with GPS to recreate the church.

The end result is breathtaking. As seen at the launch, those who are standing inside Room 60 at the National Gallery are transported to the church in 14th century Florence – and even those in Florence or sitting at home can now see and experience San Pier Maggiore the way it was during its medieval heyday!

New Technology Bringing Back History

“So often when we come to a gallery, we see a painting abstracted on a wall and we lose sight of the fact that originally it stood in a church on an altar in a huge religious space,” Professor Nevola said in a short documentary produced by the National Gallery that accompanied the unveiling.

Thanks to digital technology, it’s now possible for people in the 21st century to really get in touch with Europe’s historical roots through dynamic, immersive media—people can now virtually experience paintings on the walls of galleries in their original historical settings, bringing new context and life to these masterpieces.

Hidden Florence 3D is available for free on the App Store.