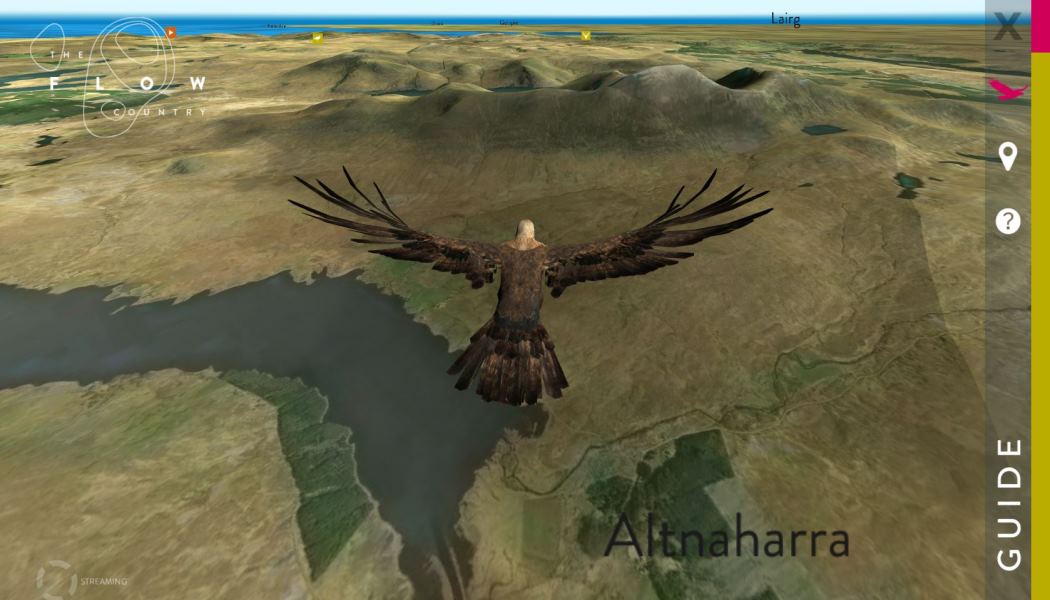

Below we focus on three case studies that show the comprehensive nature of multimedia guides and their worldwide reach such as PEEL Interactive’s project on a 200,000 hectare RSPB visitor centre in the Scottish Highlands, the versatility of platforms such as City-insights’ work on projects inside museums and out on the city streets and how apps can be adapted to a specific project such as Xponia’s recent work with Kids in Museums.

We also talk to Tim Powell, digital producer at Historic Royal Palaces (HRP), about the development of new digital visitor experience devices and the experimental visitor experience the Lost Palace Project that took place on the streets of London this summer and which you can find out more below as we republish our case study from December 2015.

HRP will start rolling out its new digital visitor experience at Hampton Court Palace over the winter. The project has been ongoing for the past year and Powell says it is core to the visitor experience. Incorporated into the latest iteration of HRP’s multimedia devices will be technology that was tested as part of The Lost Palace project which used audio and haptic technology to allow visitors to rediscover the destroyed Whitehall Palace and the events leading up to the execution of Charles I through the beat of his heart.

However, Powell insists that the absolute key when it comes to multimedia guides is not to think about the technology, but what is special and unique about an organisation’s offer; and that the digital information is presented in the same style, tone and voice as the other communications and that it is fully integrated into the visitor experience.

“Creating and updating the multimedia guides has to link with how we deliver our content on the website – it all has to be integrated into the journey,” he says. “But it’s about more than delivering information, it’s about a relationship.”

The visitor expectation of what multimedia guides provide has grown over the years and now visitors expect many extras such as a map to show where the exhibits and toilets are, what’s on on a particular day and to have access to all the peripheral elements to their visit.

“This will be all be incorporated in the new digital visitor experiences that will be handed out to HRP visitors from this winter,” he says. “The Lost Palace was very different as it was an experimental experience and not the same as a multimedia or audio guide. It was testing technology.”

Powell says that The Lost Palace experience has informed HRP in the way it delivers its more traditional and mainstream visitor guides and one of the successes was the use of binaural recordings. This replicates how we hear things in a 360 degree or 3D manner and is achieved by using two microphones recording inside a dummy’s head and will now be incorporated into the new multimedia guides over HRP’s six sites.

But while Powell works on the latest developments in multimedia guides he is also mindful that they can in their nature put up barriers to heritage sites and centuries old buildings. He says that multimedia guides have the potential to supress the visitor’s experience if they are constantly staring down at a screen with the interesting challenge being how to get that balance right.

“Speaking specifically from a heritage and historic building point of view it’s being able to stand in that room and experience the history. Audio guides do not intrude on that, however, with the trend of more organisations moving towards multimedia guides the danger is that they become intrusive.”

Powell says that HRP will aim to open more experimental experiences separate from the standard visitor experiences in the future and continues to keep his eye on developments in this field.

One such technological development that is on his radar at the moment is Google’s Project Tango, which he believes is one of a few technologies that may well enter widespread use in the coming year and be used in museums as a result.

Tango uses computer vision to enable mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets, to detect their position relative to the world around them without using GPS or other external signals. This allows them to recognise architectural features and thereby know exactly where the user is within the building. “This opens up exciting possibilities for triggering content based on where the visitor is and how they move through the building – and also with way-finding by showing the route from where the visitor wants to go as a path on a real-time camera view of their location.”

Previous In Focus Features

Collections: making museum treasures more accessible and better cared for

Exhibition Design – finding innovative ways to bring collections and audiences together

Audience Development: Putting visitors at the heart of the museum

Digitising Collections – breaking through the museum walls and opening up collections to the world

Technology in Museums: making the latest advances work for our cultural institutions

Income generation: developing cultural enterprises in museums and heritage attractions

Accessibility in museums: creating a barrier-free cultural landscape

Temporary and Touring Exhibitions: Reaching out to new audiences

Packing and transporting museum collections – how to get it right

In Focus: collections management – connecting objects and people

The balancing act of designing permanent exhibitions

Valuing, insuring and securing collections