With increased threats of cuts in museums, and the role of the curator being more demanding, the British Museum held a one day conference on 13 April 2015, titled ‘Curator of the Future’. I couldn’t attend the conference, but I watched the goings on from Twitter (#futurecurator). There were several themes that came up including museum studies courses (which may not be as hands on as they could be) to a lack of jobs in museums, so the conference covered a lot of ground.

One of the main focuses of the tweets was making things more accessible through digital media, loans and improved partnerships. Making collections digitally accessible allows them to be viewed outside of the museum, in the comfort of someone’s own home. Although this takes away the atmospheric experience of visiting a museum, someone in China can easily view some objects from Plymouth. Loans and partnerships allow collections to be seen by people from outside the local area. All of us working in museums know how we can get our collections to be more visible. And being more visible means that people know the collections are there.

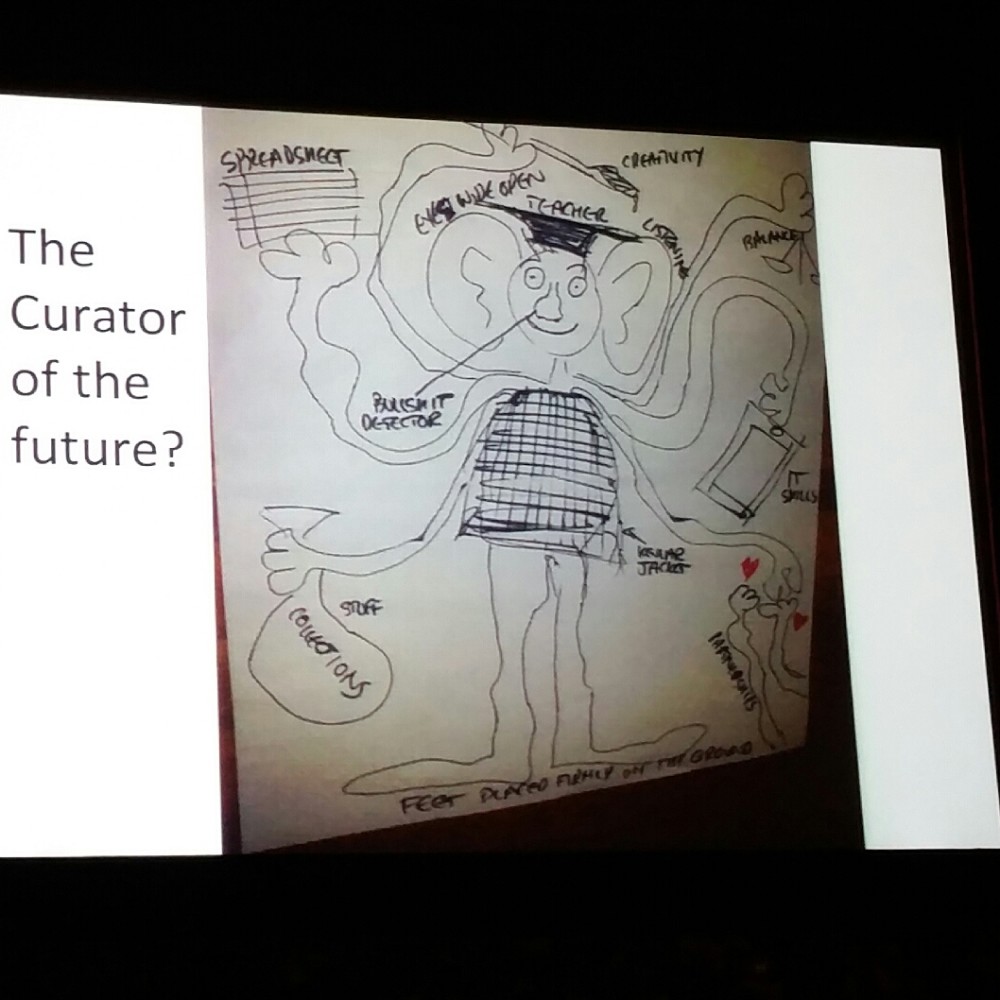

There are more pressures on museum curators today than 100, or even 20, years ago. We are expected to do more and with less money. We have a huge backlog of thousands of specimens to input into our electronic databases, pack hundreds of objects so they are safe for future generations, organise events using the collections, create new displays, make loans, give talks, educate school groups and more! The skills for the museum curator extend further than their subject specialism.

Is all this ‘extra’ such a bad thing? I would argue, not. I would also hope that other curators who are passionate about the collections they look after would argue the same. Over the past century the essence of the museum curator’s role has essentially stayed the same. All curators, regardless of department, care for the collections they are in charge of. This involves documentation, conservation, and research of objects along with creating displays in the museum. Since the 1990s curators have spent many hours behind the scenes painstakingly working through collections to update their databases. For collections that hold tens (or even hundreds) of thousands of specimens, this is a Herculean task. A task which continues today.

Documenting museum collections is essential for museums to know exactly what they have. Without even a basic level of documentation (specimen number, identification, date collected and collection place) collections cannot be utilised to their fullest potential. If we don’t know what we have in our store rooms, we can’t let other people know. And this is where the biggest change for curators in the last century has been: telling people what we have in the collections. And not just telling researchers but the people who own museum collections in the UK: the general public.

Curators today are not hidden in dusty old store rooms. Curators today are out and about engaging with people: running events in the museum, in the city, talking on the local radio or filling up social media with cool photos of their collections. There are many museum curators on Twitter interacting with the public each day. We are more accessible than we ever have been before which is fantastic for us to share our passion and for the public to feel closer to the collections. No longer do curators shuffle through a museum avoiding eye contact with the public. Those days of seeing a museum curator give a talk only to strain to hear their mumbling, muffled words are long gone. The old school curator has almost retired. Before, engagement was a different place from what we know today.

The curator of the future is adaptable, passionate, enthusiastic, and smart. Although the majority of museum curators today are involved heavily in engagement, it doesn’t mean that the work behind the scenes has been left behind. The documentation still continues, and this is where the ‘smart’ bit comes in. Being smart about planning projects to deal with segments of our collections, at a time linked in with engaging activities, allows curators to attack an otherwise insurmountable challenge in manageable chunks

With this brave new world of engagement more and more people are seeing museum collections than ever before. More are hearing the stories behind objects, and meeting the real people who look after them. The stories of not only the specimens, but the collectors, are not locked away anymore. Curators are not just custodians of incredible collections, we are passionate about them and want to share our knowledge to encourage new uses and inspire new audiences.